Frequently Asked Questions

Click on ![]() to expand text.

to expand text.

How to use this website.

The Wing Institute website is designed to provide education policy makers (federal, state, and local), professional development providers (pre-service and in-service), school personnel (principals, teachers, and support), and community stakeholders (parents and community at large) with useful information for making empirically based choices needed to build quality education services.

For the convenience and benefit of visitors, the website is designed to access information through multiple entry points. Begin navigating the site by exploring the top navigation bar:

Evidence-Based Education This section contains information on the foundation features of an empirical model of education. These features include measuring the impact of services, issues inherent in taking practices from research to practice, the need for standards of proof, how to understand and interpret research, and why science is essential.

Education Drivers Eight drivers encapsulate essential practices, procedures, resources, and management strategies associated with high-impact skill acquisition, student achievement, and success in school. The drivers can be explored using intuitive graphics leading to a detailed review of each topic. Clicking on a driver brings up an abstract, a comprehensive overview, the Wing Institute resources, access to external research, and information on organizations that specialize in the topic.

Roadmap for Success The roadmap is a systematic method for creating a continuous improvement process for making decisions, implementing practices, and monitoring the effects of education interventions. Clicking on “DECIDE,” “IMPLEMENT,” or “MONITOR” in the Roadmap overview graphic or in the drop-down menu guides the visitor to a detailed examination of the components of the roadmap.

System Dashboard This section provides a snapshot of what the American education is doing and how it is doing. The dashboard analyzes, organizes, and synthesizes the enormous, complex, nuanced, and rapidly growing database of research, school improvement initiatives, policies, student performance, and systems performance.

News The news section connects users to the latest news and activities in the field of education. It provides access to the Wing Institute’s most recent posts as well as entry into archived news reports.

FAQ This section contains a concise list of the most commonly asked questions with answers to help visitors use the site.

Research This section makes available all the research, by topic, presented on this website. It is meant to provide visitors with extensive information about evidence-based education used to support conclusions found on the site. The topics are organized around the eight education drivers.

About Us This section offers users access to information about the Wing Institute, Wing Institute presentations, Wing Institute publications, student research funded by grants from the Institute, and summaries of the Wing Institute Summits (conferences sponsored by the Wing Institute).

What are Education Drivers?

Education Drivers are the eight factors that consistently produce the greatest impact in boosting skill acquisition, student achievement, and success in school. The Wing Institute distilled these factors from more than 60 years of empirical research.

Research reveals that not all interventions are equal. Some produce powerful results. Others are compellingly promoted but produce poor or even negative outcomes. Sometimes schools are enticed into adopting promising interventions that ultimately fail because of unsustainably high costs. To help stakeholders interpret and then select practices that are a good fit and offer the greatest likelihood of success, the Wing Institute has distilled eight essential practices, procedures, and strategies from over 60 years of empirical research. These eight Education Drivers consistently have shown the greatest impact on skill acquisition, student achievement and success in school:

Decision Making

Implementation

Monitoring

External Influences

Quality Teachers

Quality Leadership

Effective Instruction

Education Resources

What is the Roadmap for Success?

The Roadmap for Success is an evidence-based model for making decisions, implementing practices, and monitoring the effects of education interventions. When most educators hear the term “evidence-based,” they think of research based on solid science, or more specifically, using research to make smart choices that produce positive results. Conventional wisdom suggests that once we know what works, it is a simple matter to apply new interventions in real-world education settings and then watch schools reap the benefits. The problem is the education landscape is strewn with interventions that have ample supporting research but fail miserably. There are also many examples of programs with poor or no research backing that are adopted and continue to be implemented despite poor outcomes.

It is obvious something is missing in current evidence-based models. How can it be that so much quality research is producing so little? The answer lies in the complexity and challenges inherent in bridging the gap between research and practice. An evidence-based model that produces results requires much more than a simple focus on selecting the right practice. What is needed is a way to join decision-making, implementation, and monitoring into a dynamic model designed to adjust to and accommodate the reality of how schools operate.

Decision Making (How do we decide?): Many variables go into a decision about which intervention to adopt and implement. By using both efficacy research (how interventions perform in highly controlled settings) and effectiveness research (how interventions perform under real-world conditions in which there is minimal control for student characteristics, setting features, resource demands, and social contingencies), educators can significantly increase the likelihood of making improved choices to better meet the needs of students.

An evidence-based decision-making framework emphasizes three components: (1) best available evidence, (2) client values, and (3) professional judgment. By examining efficacy research and effectiveness research, educators can more effectively use the existing knowledge base.

Implementation (How do we make it work?): This critical feature of the Roadmap addresses all relevant variables so that an intervention can be successfully adopted and sustained. Successful implementation requires careful planning, consideration of how the intervention will mesh with current practices, adequate resources for the intervention, training and support for those responsible for the intervention, and a method for evaluating the impact of the intervention and making rapid adjustments as needed to improve benefit.

Monitoring (Is it working?): Because no intervention will be universally effective, frequent monitoring of effects is necessary so that decisions can be made on how to proceed. Infrequent monitoring only wastes resources and time when an ineffective intervention is left in place too long. It is also essential to monitor how well the intervention is implemented (treatment integrity). That’s the only way to know whether an intervention is effective or ineffective and whether it was implemented properly or so poorly that benefit cannot reasonably be expected. Knowing about the quality of implementation allows practitioners to make data-informed judgments about the effects of an intervention. Making judgments about the effects in the absence of data about the quality results in guessing and, in some instances, discontinuing interventions that would be effective if implemented properly.

Summary

Ultimately, the effective implementation of classroom practices designed for individual students or systemwide school improvement initiatives requires educators to address all three key elements of the Roadmap. The combination of evidence-based decision making, implementation, and monitoring are key to consistent services across schools that encourage continuous improvement and interventions that are sustained over time.

What is Systems Dashboard?

The system dashboard provides a snapshot of the latest data on what schools are doing and how they are doing. The dashboard analyzes, organizes, and synthesizes the enormous, complex, nuanced, and rapidly growing database of research, school improvement initiatives, policies, student performance, and system performance. What follows are the four main parts of the dashboard.

Structural Interventions This area of the site examines data on common practices including charter schools, school choice, increased funding, class size reduction, computer-assisted education, and accountability. These practices are analyzed to better understand the impact they have on critical outcomes.

Policy Initiatives Policies are explored with an emphasis on interventions designed to produce notable outcomes and those initiatives that fail. The various interventions and their impact on critical student, societal, and system outcomes are analyzed, reviewed, and reported on. Policies examined include Every Student Succeeds, Race to the Top, school turnaround, teacher evaluation, and Common Core.

Societal Outcomes The dashboard examines the overall performance of the education system in achieving critical goals that meet society’s needs. Data on progress in accomplishing meaningful equity, efficiency, participation, and long-range societal outcomes are offered for review.

Education Outcomes This portion of the dashboard looks at outcomes directly related to students, staff, schools, and the education system. Examining these performance categories against expectations and making interstate and international comparisons are essential to better understand the overall effectiveness of schools.

What factors have the biggest impact on student achievement?

Research informs us that the two most influential factors are teachers and school principals.

Over 30 years of research provide educators and decision makers with the quantity and quality of evidence about factors that play the biggest role in boosting achievement. First, let’s set ground rules. Research informs us that some of the most powerful factors controlling achievement occur outside school. For example, we know that socio-economic status (SES) have profound effects on predicting a child’s future success in school. Unfortunately, school systems have no control over a student’s SES and other outside factors that schools can control. The two most influential factors are teachers and school principals.

Teachers

- Classroom management

- Instructional delivery

- Formative assessment

- Soft skills

Classroom Management: Fundamental to a teacher’s success is his or her command of student conduct. Setting classroom rules, providing effective training, affirming proper conduct, and responding in a timely and consistent way to inappropriate conduct are essential elements of effective teaching. Only when a teacher has established instructional control is the classroom ready for effective instruction to begin.

Instructional Delivery: Teachers who embrace an explicit model of instruction have a significantly greater impact on achievement than those who employ a less directive instructional style. Research on explicit instruction reveals that planning is the indispensable foundation on which to build effective instruction. Teachers who develop instructional objectives, link lessons through the use of scope and sequencing, tie instruction to “big ideas,” and connect lessons to standards are the most successful. Providing each student with a sufficient quantity of instruction and opportunities for high rates of responding is essential for effective delivery of instruction. A hallmark of effective teaching is the proficient use of feedback. Teachers who provide comments in a supportive manner that inform the student about how to improve and acknowledge when the student succeeds see higher student achievement. Finally, students must master material before moving on to the next lesson, and teachers must return to previously learned material in future lessons as well as encourage the use of acquired skills and knowledge in real-world settings so that students maintain them over time.

Formative Assessment (Progress Monitoring): Research shows that few practices have as great an impact on learning as formative assessment. Teachers who collect performance data weekly and then chart and analyze the data using decision rules see student learning notably enhanced. Even higher results can be achieved when teachers provide the results of their analysis to students. The take-home message: Frequent formative assessment systematically implemented produces remarkable results that are observable within a single school year.

Soft Skills (Personal Competencies): A review of the research reveals that when a positive relationship exists between a teacher and students, good conduct and academic achievement follow. Teachers who communicate well with students by setting clear expectations, act with authenticity, employ active listening, remain flexible, express a passion for learning, and show cultural sensitivity are more effective teachers.

Principals

Principals rank second after teachers in influencing student achievement. Almost a quarter of the impact that schools have on student performance can be attributed to how well a principal does his or her job. This far outweighs the impact of popular interventions such as class size reduction, spending, charter schools, longer school years, and homework.

What is astounding about the powerful role they play is that, for the most part, principals do not work directly with students. The principal’s influence comes from effective leadership in inspiring faculty members to do their jobs well. This mediated effect makes the job of school principal one of the most challenging in a school.

Research on school principals reveals five dimensions of leadership that are linked to higher teacher performance and ultimately produce the greatest gains in student achievement.

- Leading teacher learning and development

- Establishing goals and expectations

- Ensuring quality teaching

- Resourcing strategically

- Ensuring an orderly and safe environment

Leading Teacher Learning and Development: The effective principal directs the school’s professional learning so that teachers are well trained and have the necessary instructional skills to achieve the school’s objectives. To be a competent leader, the principal must ensure that effective pedagogy is used in training and that instructional skills are sustained over time. The principal must also be committed to delivering professional development that goes beyond mere paper compliance with district or state mandates; the effects of training must be observable in classrooms.

Establishing Goals and Expectations: The most successful principals are ones who systematically solicit input from faculty members and others, and then use it to set, communicate, and monitor learning goals, standards, and expectations. These principals produce results most likely to achieve the aspirations of the communities they serve.

Ensuring Quality Teaching: Principals who regularly visit classrooms and use formative and summative assessment are more likely to obtain best results from their faculty and students. By becoming directly involved in supporting and evaluating classroom instruction, they are in a better position to oversee schoolwide instruction across classes and grades so it is aligned with school goals.

Resourcing Strategically: Principals who effectively acquire, allocate, and align resources with teaching goals are more likely to achieve favorable results. The focus is not on gaining more resources, but on using existing resources strategically.

Ensuring an Orderly and Safe Environment: Effective principals ensure that staff and student feel physically and emotionally safe. They must provide adequate time for instruction and learning by reducing external pressures and interruptions, and by establishing an orderly and supportive environment both inside and outside the classroom.

What are the most important changes a school principal can make to improve their school?

Research on school principals reveals five dimensions of leadership that are linked to higher teacher performance and ultimately produce the greatest gains in student achievement.

- Leading teacher learning and development

- Establishing goals and expectations

- Ensuring quality teaching

- Resourcing strategically

Ensuring an orderly and safe environment Leading Teacher Learning and Development: The effective principal directs the school’s professional learning so that teachers are well trained and have the necessary instructional skills to achieve the school’s objectives. To be a competent leader, the principal must ensure that effective pedagogy is used in training and that instructional skills are sustained over time. The principal must also be committed to delivering professional development that goes beyond mere paper compliance with district or state mandates; the effects of training must be observable in classrooms.

Establishing Goals and Expectations: The most successful principals are ones who systematically solicit input from faculty members and others, and then use it to set, communicate, and monitor learning goals, standards, and expectations. These principals produce results most likely to achieve the aspirations of the communities they serve.

Ensuring Quality Teaching: Principals who regularly visit classrooms and use formative and summative assessment are more likely to obtain best results from their faculty and students. By becoming directly involved in supporting and evaluating classroom instruction, they are in a better position to oversee schoolwide instruction across classes and grades so it is aligned with school goals.

Resourcing Strategically: Principals who effectively acquire, allocate, and align resources with teaching goals are more likely to achieve favorable results. The focus is not on gaining more resources, but on using existing resources strategically.

Ensuring an Orderly and Safe Environment: Effective principals ensure that staff and student feel physically and emotionally safe. They must provide adequate time for instruction and learning by reducing external pressures and interruptions, and by establishing an orderly and supportive environment both inside and outside the classroom.

Why do so many school initiatives fail?

This is one of the most vexing questions facing educators. Although there is no one solution, clear answers to why initiatives fail do exist, along with proven ways to significantly increase the success rate of interventions.

The failure rate of school interventions is exceedingly high. On average, education interventions fail within 18 to 48 months of implementation. Identifying the reasons for failure should be the highest priority for policy makers, but this issue has not yet received the attention it deserves. Initiatives fail for many reasons including:

Initiatives fail because of poor decision-making protocols during the selection phase. Poor protocols result in too many interventions being chosen for reasons other than quality evidence. The consequence is that even the best efforts by principals and teachers may not be successful.

Initiatives fail because decision makers did not obtain buy-in and support from teachers and school staff, who must carry out the intervention. Trying to implement an initiative when it is clearly opposed by the majority of personnel significantly increases the likelihood of failure.

Initiatives fail because the people who must implement the intervention are inadequately trained in the practices and procedures essential to the initiative.

Initiatives fail because they are not implemented with treatment integrity. Even an effective practice is likely to fail if it is not implemented as designed.

Initiatives fail because the people responsible for supervising the intervention are not sufficiently involved and don’t adequately oversee the staff who implement the intervention. Without feedback, teachers and other responsible staff are likely to fall back on what they know best, leaving the initiative to die from inattention. Initiatives must be nurtured to ensure they are being properly implemented.

Initiatives fail because they are not incorporated into the culture of the school (how things are done in the school). For sustained initiatives, contingencies supporting the intervention must be in place and operating. Research suggests that it takes 5 years for a new intervention to be fully implemented.

These are a few of the reasons initiatives fail. Implementing any intervention is a complex enterprise requiring extensive planning, training, opportunities to adapt and make improvements, and supervisory oversight. For a detailed analysis of how to effectively implement initiatives, go to the Roadmap for Success.

How can educators best interpret evidence when selecting practices?

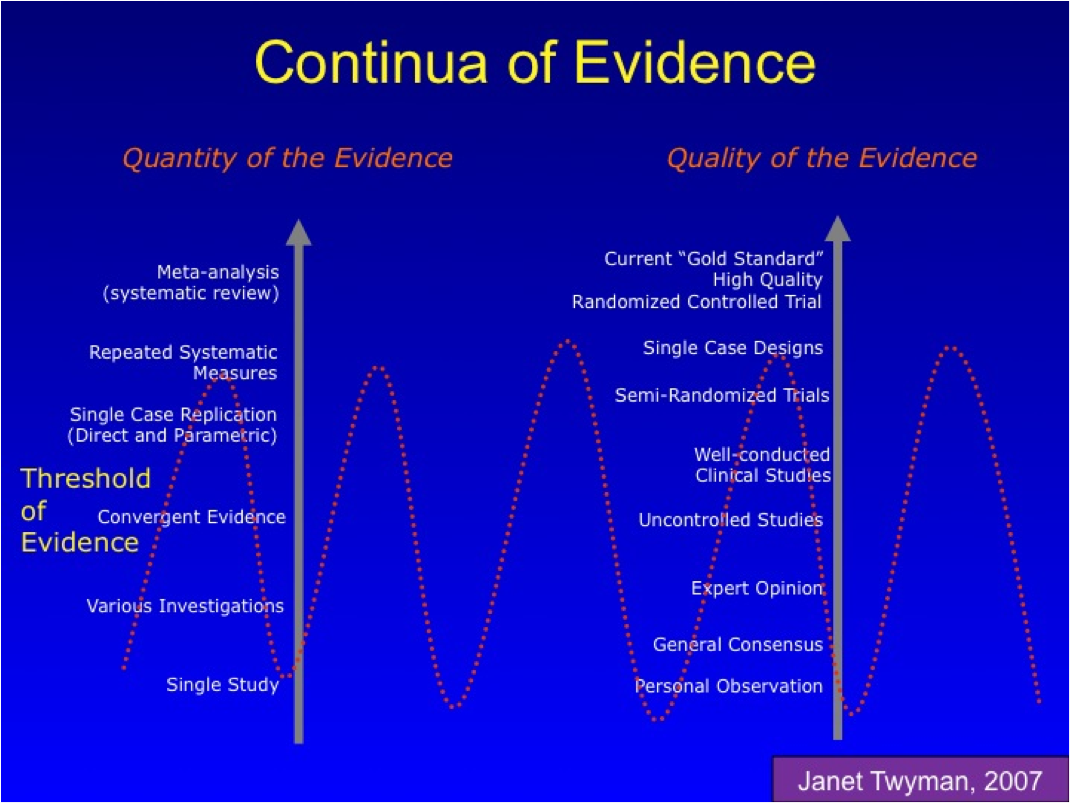

There are two factors to consider when interpreting evidence. The first is quality. Is the research design capable of establishing a causal relationship between an intervention and outcomes? Does the intervention reliably produce the intended results? The second factor is quantity. Are there multiple studies of the intervention available? A single study is rarely sufficient.

The interpretation of research is complicated and often confusing for non-experts. Without regularly reading research, most people find it challenging to understand how a particular study can help policy makers, practitioners, or parents make useful decisions. How does a person decide what works, what doesn’t work, when it’s working, and what alternative choices are available for a practice that isn’t working?

A familiarity with the following topics is essential for interpreting evidence effectively:

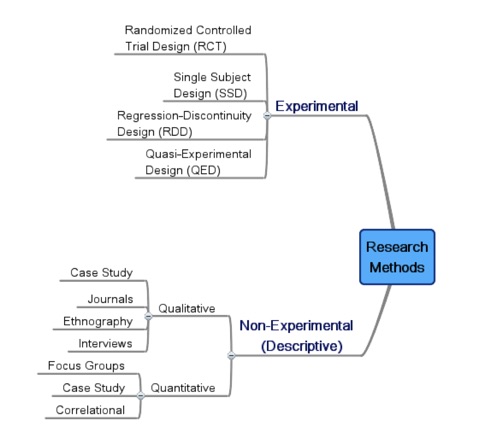

- Research techniques

- The most common methods of research available in the field of education

- The strengths and weaknesses of the different methods

- How to determine the quality of research

- Were the research results consistent over time and in different settings?

- Have the research results been replicated through multiple studies produced by different researchers?

- How to interpret the results: The importance of two valuable research tools

- Effect size

- Meta-analysis

What is Research?

Research is the process of collecting and analyzing information to increase our understanding of a phenomenon. The process can be as simple as investigating through observation or as complex as experimenting to establish a relationship between cause and effect. Information derived from systematically accumulated observations and investigations can be organized into theories and laws about how the world operates.

In taking research to practice, we translate these theories and laws into programs and treatments. We do this so that we can reliably achieve desired results when we consistently implement programs and treatments. Research enables policy makers and practitioners to make smart decisions. For example, when testing a new reading program, researchers have a concept of how the program should work. Educators have goals for what the program is to achieve and how it will affect a student’s reading ability, and a plan for measuring this effect. By conducting research, we increase the likelihood that our reading program will reliably produce competent readers over time.

What is achieved through research:

- Replicable results

- Results that best match educators’ expectations

- Results that reduce the risk of students falling behind expectations

- Identification of flaws and deficits in current practices

- Increased likelihood of success for future students

Various research techniques

Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Research studies are categorized as either qualitative or quantitative.

- Qualitative research takes a descriptive rather than a numerical approach. Information is collected through observations, interviews, and surveys.

- Quantitative research relies on the collection and analysis of numerical data for the purpose of describing and explaining phenomena. The data is derived from both observation and measurement.

Non-Experimental and Experimental Research

1. Non-Experimental Research

A non-experimental design describes observed events without influencing the experience. This is a strong type of research when the intent is merely to describe a phenomenon. This design is especially important when little is known about the phenomenon and the researcher needs to collect sufficient information before proposing experimental studies. Non-experimental designs are weakest with respect to internal validity, the ability to assess the causal relationship between an intervention and outcomes.

Simple and Comparative Descriptive Designs

These designs are used simply to describe what is observed or to compare different observations.

For example, a researcher administers a survey to a sample of first-year teachers in order to describe the characteristics of novice teachers. Simple descriptive studies include case studies, journals, ethnographies, and interviews.

Correlational Research

This type of study, which can be either qualitative or quantitative, often is cited in the media as proof of a breakthrough. Correlational research is good at describing a statistical relationship between variables, but it cannot be used to establish cause and effect. For example, a correlational study may suggest that that students who study are more likely to score higher on tests than students who don’t study. This sounds correct, but there is no proof that studying leads to higher grades. By adopting a practice supported by correlational research, teachers may be making a mistake by committing to an intervention that fails or takes valuable resources away from more effective interventions. Correlational research is useful in guiding researchers on where to apply more exacting methods of research, but it shouldn’t be confused with more rigorous research methods designed to established causal relationships.

2.Experimental Research

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

RCT is an experimental method in which investigators randomly assign eligible participants into groups to receive or not receive one or more interventions that are being compared. It is considered the gold standard for research whose goal is to assess the causal relationship between an intervention and outcomes. RCT relies on statistical methods to determine the magnitude of the effect. Randomized controlled trials must be internally valid, meaning they must be designed and conducted to minimize or eliminate the possibility of bias. They must also demonstrate external validity, or the ability to generalize the results from the research setting and participants to other conditions and populations. The lack of external validity is the most frequent criticism of this type of experiment.

Single-Subject Design (SSD)

In this experimental method, the researcher tries to change the behavior of an individual or small group of individuals, and to document the change. For example, the goal may be to track how many times one or more students disrupt a class over several days, and then track the disruptions after an intervention such as praise is introduced. SSD is very effective in establishing internal validity (lack of bias), but is limited in external validity, or generalizing to larger groups or different conditions.

Regression-Discontinuity Design (RDD)

This experimental method is a pretest-posttest comparison group design (participants are studied before and after an intervention). It differs from the randomized controlled trial in how participants are assigned to the comparison groups. RDD assigns participants on the basis of a cutoff score on a pre-intervention measure, whereas RCT randomly assigns participants.

Quasi-Experimental Design (QED)

As an experimental design, QED is more subject to threats to internal validity (lack of bias) than RCT or RDD designs. Whereas RCT assigns participants to groups randomly and RDD assigns them based on a cutoff score, QED uses some other method of the researcher’s choice. This lack of rigorous assignment introduces the potential for selection bias that may limit the ability to make sound conclusions about cause and effect.

How to establish the quality of research

In an evidence-based environment, educators must interpret the results of research on continuum of evidence to determine if the conclusions meets the threshold required for making smart decisions. The continuum consists of two factors: the quality of evidence and the quantity of evidence.

Quality of Evidence

A cornerstone of an evidence-based approach is quality of evidence, or the confidence that educators have in the conclusions derived from the study. In looking at the quality of a study, we determine the strength of its evidence as measured by internal validity (lack of bias). As educators, we also want to know how likely we are to achieve similar results when we implement the practice (a question of external validity). As the quality of the experimental design increases, so does the internal validity. The continuum of evidence starts with low-quality designs such as personal observation and no control for threats to internal validity and culminating in the gold standard of designs, the randomized controlled trial.

Quantity of Evidence

Another cornerstone of an evidence-based approach is quantity of evidence; that is, lots of studies that examine the same phenomenon. One study does not offer conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of a practice. Scientists gain confidence in their knowledge by replicating findings over time through multiple studies conducted by independent researchers, to show that the results were not an anomaly.

How to interpret results

One of the great challenges for educators in using research is how to plumb through the volume of studies as well as the information within a study. Fortunately, over the past 30 years two valuable tools have been developed to help educators understand research: effect size and meta-analysis.

Effect Size

Rather than a research design or a method to establish causal relationships, effect size is a statistical approach to understanding research results. It is a standardized measure to assess the magnitude of an intervention’s effect, which helps determine how powerful an intervention is.

Effect sizes range from minus to positive, with no limit on either end of the distribution. A common measure of effect size is Cohen’s d. A small effect size is commonly defined as small =0.2, medium = 0.5, and large = 0.8. Occasionally, effect sizes exceed +1.0. The terms “small,” “medium,” and “large” are relative. Researchers accept the risk of using relative terms in the belief they have more to gain than lose when no better way to estimate the impact of an intervention is available.

| Cohen’s d* | Effect Size |

| Small | d = 0.2 |

| Medium | d = 0.5 |

| Large | d = 0.8 |

* The accepted benchmark for effect size comes from Jacob Cohen (1988), a U.S. statistician and psychologist.

Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis is a literature review that uses statistical techniques to combine the results of individual studies into an overall effect size. It is not itself a research design or an actual scientific study, but rather a method to statistically examine scientific studies of a single subject. A meta-analysis can be extremely helpful to educators in making sense of multiple studies on a single topic.

What are the best teaching strategies and most critical skills for staff development?

Teachers are most effective when they demonstrate proficiency in four important competencies:

- Classroom management

- Instructional delivery

- Formative assessment

- Soft skills

Equally important is how professional development is delivered. In 2015, the United States spent on average of $18,000 for each teacher per year on staff development, a substantial allocation of time and resources. These dollars are most frequently earmarked for teacher induction and in-service workshops. Unfortunately, there are very few studies that examine this type of training and whether it addresses the four critical teaching competencies, employs coaching to maximize the transfer of learned curriculum from training to classroom, or achieves sufficient results to justify the cost.

All too often, professional development is diverted from critical skills training to accommodate instruction in mandates passed down from above or the latest fad that suddenly emerges only to fade away by the next school year. Professional development planning is essential for successful training. Training that does not take into account the need to integrate new practices into the culture of the school is doomed to failure. Teachers are overwhelmed with new prescripts that many feel are ineffective and distract them from more pressing tasks. Taking this attitude into consideration, professional development planners must look for ways to introduce new practices compatible with current practices and emphasize their value to both students and the teachers. Planners should also identify ineffective or unnecessary practices and eliminate them from teachers’ workload.

How can teachers gain control of their classrooms?

The key to establishing a classroom climate conducive to learning is to offer stimulating lessons, set clear classroom rules and standards of behavior, affirm proper conduct, and respond quickly and consistently to inappropriate behavior.

The most effective way for a teacher to gain control of a classroom is through the systematic use of classroom management practices: offering stimulating lessons, setting clear classroom rules and standards of behavior, affirming proper conduct, and responding quickly and consistently to inappropriate conduct.

Principals and teachers commonly rank classroom management among the top critical teaching skills. Disruptive student behavior is listed at the top of teachers’ concerns and a prime reason teachers leave the profession. Research confirms these impressions. We now confidently know that a teacher’s success depends on his or her command of student conduct. Furthermore, evidence shows that a well-managed classroom plays a powerful role in student learning and achievement.

How do teachers manage demands that keep them from focusing on teaching?

Managing time to ensure important tasks are accomplished is one of the greatest challenges facing teachers in the 21st century.

- Provide diagnostic assessment

- Administer remedial instruction

- Enhance instruction for the gifted

- Integrate special education students into the general education setting

- Instruct bilingual students

- Provide essential social services

- Adapt lessons to address long-range goals and standards

- Offer instruction toward standardized testing

- Plan lessons

- Execute effective classroom management

- Acquire essential resources

- Ensure compliance with federal, state, and local mandates

- Participate in professional development

- Engage in school-wide activities

- Coordinate with other teachers in the school

- Offer timely communication with parents and care providers

This list of responsibilities makes clear how expansive and complex the job of teaching has become. Research finds the average teacher spends between 50 and 55 hours per week doing the job. The notion teachers work short hours is simply a myth.

To accomplish all that is expected requires a high degree of discipline and effective time management. Becoming overwhelmed by this heavy workload is a constant challenge and dictates that teachers engage in a high degree of planning and judgment to manage the tasks.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, multitasking is not an option. Research finds that human beings are not actually capable of completing more than one task at a time. In reality, they jump back and forth between tasks, concentrating on only one activity at a time. Teachers need to take this into consideration and build adequate time into the schedule for completing their numerous tasks. This requires setting aside time with minimal opportunity for interruptions to review the previous week’s efforts to assess which tasks were met and plan for the coming week. Planning requires prioritizing actions in order of relevance, deadlines, consequences, and time required for completion. Not all activities are equally important and teachers need to make a conscious choice of which tasks to address and which to delay.

When the job does becomes overwhelming, it is important to remember a teacher is a team member who can ask peers and the principal for help in prioritizing critical duties and how best to keep the focus on accomplishing what is important: effective teaching.

How do I work with student falling behind while still moving on with my lesson plans for the group?

Teachers must provide sufficient time for students to build fluency through practice, furnish ample opportunities for everyone to respond and be actively engaged, employ formative assessment, increase motivation, and use personalized teaching methods such as peer tutoring or small groups for students requiring more attention.

This is the perpetual dilemma facing teachers. How does one person teach a group of 20 or more students who perform at different levels of competency while making sure that each student progresses? This predicament leads many teachers to adopt ineffective instructional practices out of frustration. There are too many teachers who give in to that frustration by delivering instruction through worksheets or by overusing lectures, practices that generally have minimal educational value. The alternative is to use evidence-based practices that have proven track records in actual school settings.

Formative Assessment (Progress Monitoring): To avoid being lured into adopting practices that give the appearance of teaching but leave behind struggling students while boring gifted students, teachers must embrace a model of instruction with formative assessment at its core. In an educational system that expects all students to succeed, formative assessment helps teachers to identify each student’s standing academically and to make informed decisions on adjusting instructional strategies. Teachers who wait until test day to evaluate each student are missing the boat.

Many teachers may be apprehensive about the added work that ongoing formative assessment may entail. Fortunately, achievable solutions exist. For progress monitoring to work, it needs the support of the school principal, who must make it a priority and an integral component of the school’s culture. Technology is available to make the job easier; for example, AimsWeb is a web-based system for completing curriculum-based measures. Teachers should also work together to find ways to avoid pitfalls that can make progress monitoring laborious and time-consuming. Finally, formative assessment must be viewed as central to being a good teacher. The data collected during assessment must be used to improve student performance; data collected for its own sake has no value and is an unnecessary weight on teachers.

Instructional Practices: Learning happens when students are actively engaged in the lesson. Teachers fortunate enough to have fewer than 15 students in the class can increase time spent with each student to maximize learning. Unfortunately, most teachers have larger classes. The good news is that research clearly shows students can succeed in larger classes. Offering ample opportunities to practice new material and providing sufficient time for every student to actively respond during a lesson are key to effective instruction in the typical classroom. By using active student responding to increase engagement at a whole-class or group level, teachers maximize opportunities for each student to respond. Teachers also have more chances to provide instructive feedback and to assess each student’s rate of success with the new material.

By being creative, teachers can increase individualized instruction for students who fail to master lessons in a whole-class setting. Research finds that breaking into smaller groups is an effective way to improve learning. Small-group activities increase engagement and encourage quieter students to participate. Teachers can also augment individualized time through peer tutoring, which can benefit the student who is struggling while allowing the student tutor to increase fluency. Maximizing success for all students requires adopting strategies other than a one-size-fits-all approach to teaching.

Motivation: Motivating students is a crucial part of any lesson. Because inspiring students can prove challenging in larger classes, it is especially important that teachers working with larger groups develop ways to assess and then harness each student’s drive. Ideally, the assessment will find all students enthusiastic about the lesson, but more likely it will find that some of the students are unmotivated because of past failure in the subject. Knowing that some students need more motivation can help the teacher develop special opportunities for those students to experience success. In the end, each student’s motivation is unique and must be addressed individually.