Teacher Selection Overview

In schools, teachers are the factor with the greatest impact on student achievement (Babu & Mendro, 2003; Hattie, 2009; Sanders & Rivers, 1996; States et al., 2012; Wenglinsky, 2002). Teacher quality has been expressed in terms of effectiveness in student achievement or high performance on evaluations, although many variables influence those outcomes (Stronge & Hindman, 2003). Although schools strive to hire high-quality teachers, a clear definition of “high-quality” is not easy to find. Some words that have been used to define good teachers include: analytical, dutiful, competent, expert, and respected (Cruickshank & Haefele, 2001). In addition, everyone brings their own experiences and opinions of what constitutes a good teacher (Stronge & Hindman, 2003).

Teacher selection is the process of choosing high-quality teachers from among the available applicants (Stronge & Hindman, 2006). Hiring teachers is one of the most important duties of school leaders, as teacher quality impacts student achievement and teacher turnover rates. However, a lack of clear definitions makes this key activity difficult.

Teacher hiring also has an impact on a school’s teachers and students; a good match between teacher (skills, interests, expertise) and school benefits schools and teacher job satisfaction (Liu & Johnson, 2006). Furthermore, many new teachers approach teaching as a temporary job, not a full-time career; thus a good fit between teacher and school may help transition teachers into teaching as a profession and reduce turnover (Peske et al., 2001).

The concern over hiring teachers who will stay in the classroom is a real one. Almost one-third of teachers leave within their first three years of teaching, and an additional 20% leave within the next three years (Ingersoll, 2003). Hiring managers look at many factors in considering teacher candidates for jobs. A survey of more than 600 district leaders by Frontline Institute (Combs & Silverman, 2018) found that leaders considered geographic diversity, racial and ethnic diversity, teaching experience, teaching training, and cultural fit. Teacher experience and teacher training were identified as “very important” by more than 40% of the leaders surveyed; cultural fit was the only indicator that more than 60% of leaders identified as “very important.” Although hiring teachers who are a good match for a school is significant for districts, there is no systematic definition of “cultural fit,” which may leave much to chance (Combs & Silverman, 2018).

Understanding that teacher selection is an important part of a district’s work, the purpose of this overview is to provide information about the research on teacher selection. Important questions about teacher selection include:

- What selection criteria most strongly correlate with teacher success?

- Is a teacher license a sufficient indicator of quality teaching?

- Does alternative training versus traditional certification matter?

- What hiring processes are most effective?

[A head]History of Teacher Selection

At the most basic level, teacher selection is a matter of supply and demand—the supply of teacher candidates and the demand for teachers. Districts find teachers on job boards and by word of mouth, or direct referrals. Direct referrals seem to play an important role in teacher recruitment. In a survey of 832 school districts, Combs and Silverman (2018) found that a disproportionate number of candidates were hired through direct referrals. While 15% to 16% of applications came from word of mouth, 30% of the hired candidates in a year came from those referrals. However districts find candidates, typically they struggle to find enough teachers, especially in math, science, and special education, and with diverse backgrounds (Gershenson et al., 2021; Sutcher et al., 2019).

The supply of teachers has been a concern for decades, according to the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education annual member survey (King & James, 2022). The number of undergraduate degrees awarded in teaching was stable until the early 2010s. Then, between 2005–2006 and 2018–2019, the number of people completing teaching degrees dropped by almost 22%. At the same time, the total number of bachelor’s degrees in all fields increased by 29%. In addition to the decrease in number of degrees, the past decade has seen a decline in the degrees given out in high need areas: a 4% decrease in special education degrees, a 27% decrease in science and math education degrees, and a 44% decrease in foreign language education degrees (King & James, 2022).

Federal legislation has impacted teacher selection in the qualifications that teachers must meet to be considered for teaching, and in the funding of programs to support teacher candidates. Most recently, in 2016, the Every Student Succeeds Act did not set a minimum requirement for entry into teaching and allowed states to set standards for teacher certification and licensure (Remer, 2017).

Perhaps the most significant recent event to impact teacher selection is the COVID-19 pandemic (Bill et al., 2022). The impact on teacher supply is still unclear. Will schools and districts have enough teachers to fill the spots opened by departing teachers? A teacher shortage as high as 316,000 teachers by 2025 was predicted before the pandemic (Sutcher et al., 2019), making the situation worse. The pandemic may be prompting teachers to leave the profession at a higher rate than usual, increasing demand for teachers (Pressley, 2021; Steiner & Woo, 2021; Walker, 2022).

To better understand how COVID-19 may impact teacher selection, Bill et al. (2021) conducted a survey of undergraduate students at the University of Maryland to learn about their desire to pursue a career in teaching. More than 1,500 (n=1,676) undergraduates were surveyed, and 142 participants participated in focus groups. A total of 1,254 participants were prospective teachers or had indicated an interest in teaching as a career. The prospective teachers had varying degrees of interest in teaching:

- 44% said they had considered teaching but decided to pursue a different career path;

- 13% said they were considering teaching among other options;

- 35% expressed a desire to teach in the future, after pursuing other careers; and

- 8% said they were actively enrolled in a teacher preparation program and intended to teach after graduation.

Among the respondents who were pursuing teaching, the pandemic has left a lasting impact on their interest in and perceptions of teaching. In general, they reported that the pandemic magnified their concerns about the workload of teaching and made clear a public lack of respect for the work.

On one hand, the pandemic strengthened the resolve of some teacher candidates to help students at a time when it was most needed. Some respondents saw virtual learning as an opportunity to teach, which increased their interest in teaching. On the other hand, for most respondents, the pandemic did not change their interest. More than one third (35%) said they were less interested in teaching after the pandemic, compared with 12% who said they were more interested in teaching after the pandemic. For other respondents, the pandemic pushed them farther from wanting to teach, when they saw how teachers were treated by the public. Participants also noted that COVID-19 made teaching harder, because of the transitions that teachers made and the perception of teaching had become “stressful” and “exhausting” work.

In addition to COVID-19, legislative and public efforts to control and influence what teachers teach (e.g., book bans) are among the concerns felt by teachers (Will, 2022). The full impact of COVID-19 and the current climate in education on teacher selection will become clearer in the years to come.

[A head]Questions About Teacher Selection

To staff schools with the best teachers, school leaders must maximize the process of teacher selection. To accomplish this, it is important to understand the qualities of effective teachers, how to search for and hire people with those qualities, and how to make hiring decisions.

[B head]What Selection Criteria Most Strongly Correlate With Teacher Success?

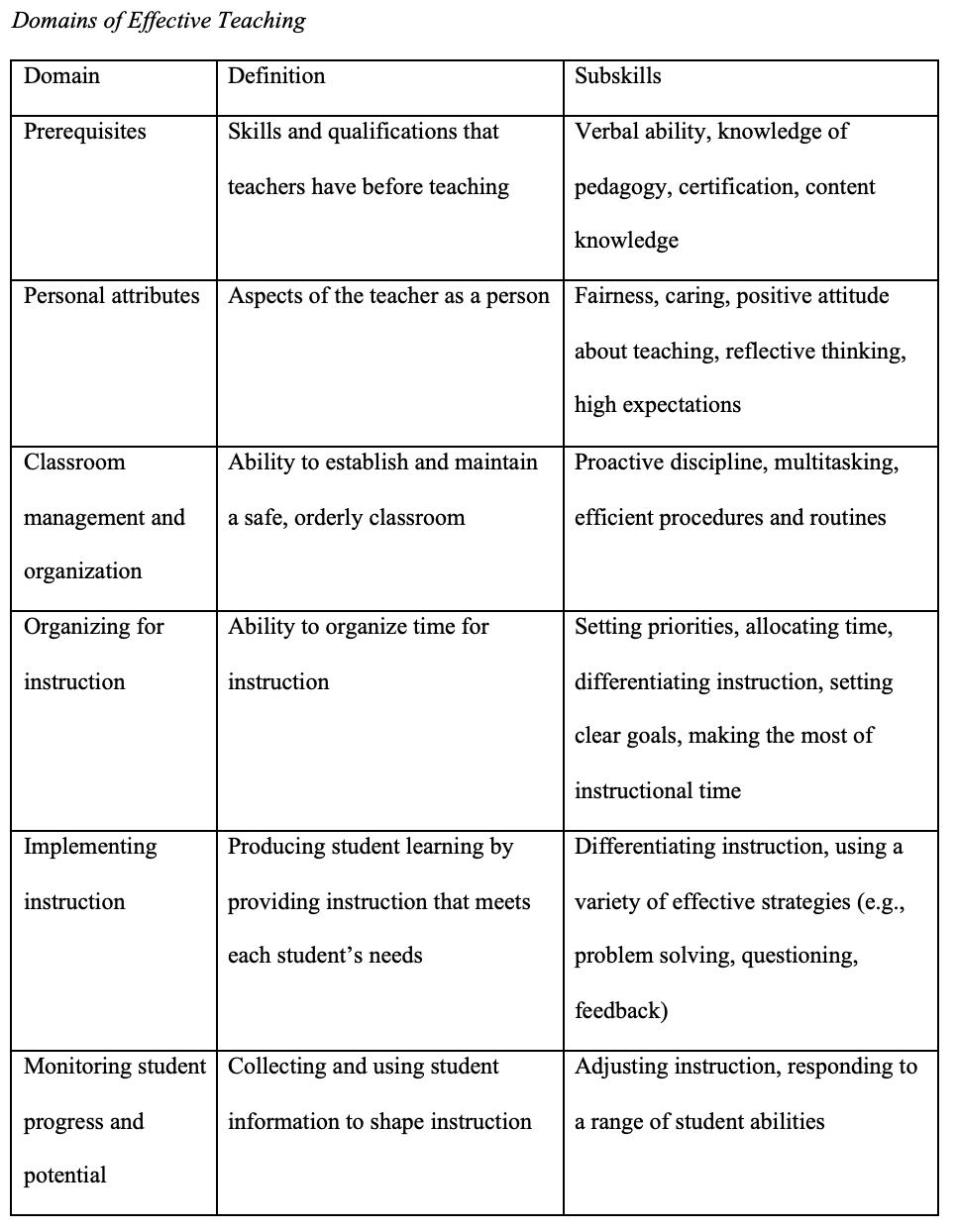

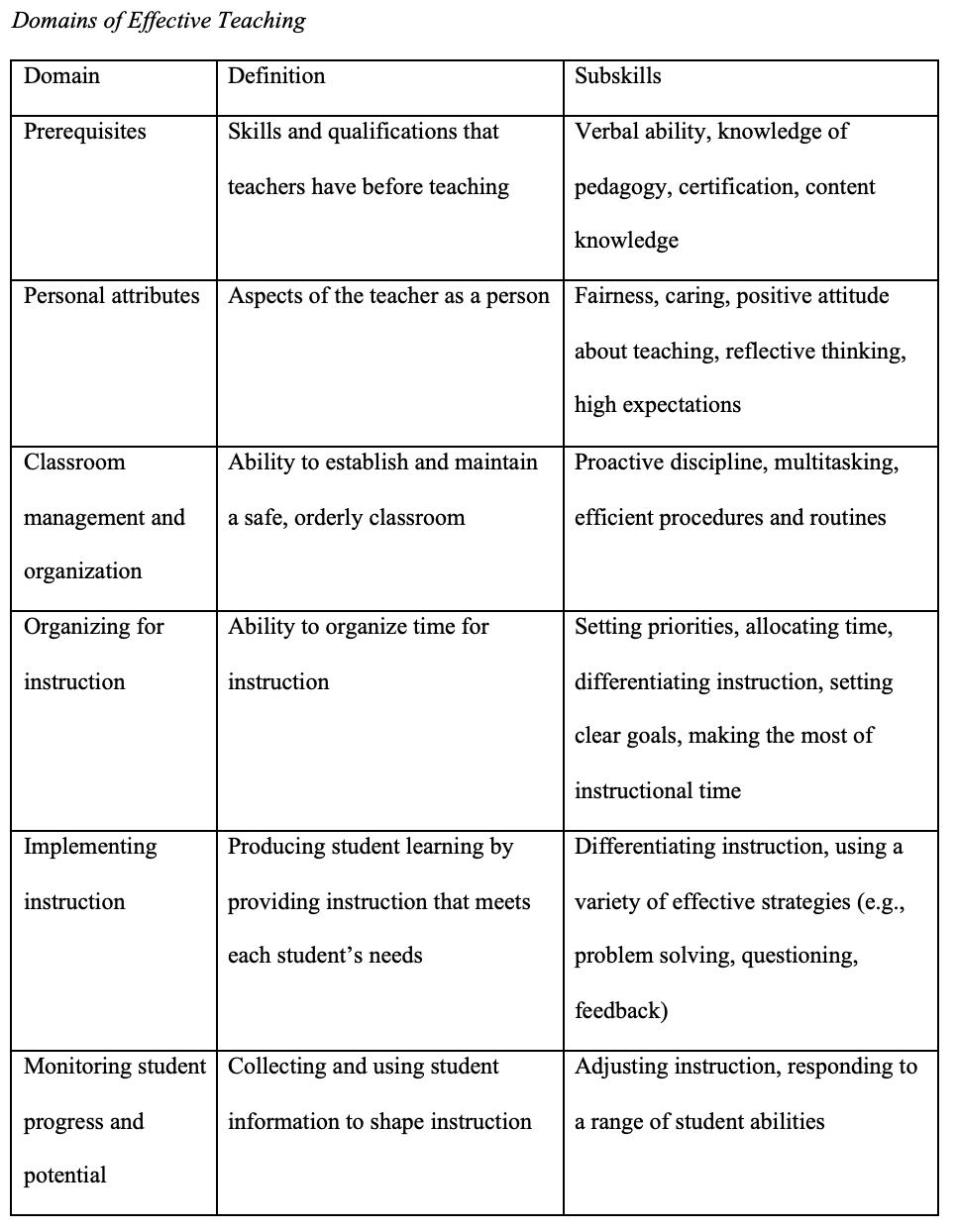

Sometimes, good teaching feels instinctive (“we’ll know when we see it”), but there are objective and measurable skills and knowledge that teachers should have and that districts can focus on during hiring. For example, Stronge and Hindman (2006) posited that we can look for research-based qualities when reviewing materials during teacher selection, and in interviews, to increase the likelihood of hiring the best teachers (see Table 1).

Teacher competencies—the skills and knowledge that a teacher must have to produce student achievement—include:

- instructional delivery,

- classroom management,

- formative assessment, and

- personal competencies (soft skills).

Instructional delivery encompasses strategies and practices that lead to student mastery of skills and content. This includes what Hattie (2009) described as explicit, active instruction. Teachers must be able to design and plan instruction that moves students from one level of competency to the next, and they must provide ample opportunities for skill acquisition (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Hattie, 2009; Knight, 2012).

Classroom management has an impact on student behavior (Hattie, 2009). Teachers must be proficient in rules and procedures, proactive in managing their classroom, and effective at reducing problem behaviors.

Formative assessment is the ongoing assessment or progress monitoring that is important for promoting student success (Walberg, 1999). Feedback, an essential part of formative assessment, improves performance by providing real-time information to students (Hattie, 2009).

Personal competencies (soft skills) are more difficult to cultivate, teach, and measure. These skills recognize that teaching exists at the intersection of skill and relationship. Personal competencies include enthusiasm for the content, high expectations, flexibility, empathy, cultural sensitivity, higher-order thinking, and positive regard for students (Cornelius-White, 2007; Marzano et al., 2003).

Table 1

Adapted from Stronge (2002) and Stronge & Hindman (2006)

[B head]Is a Teaching License a Sufficient Indicator of Quality Teaching?

All states require a minimum standard for teacher licensure or certification, which may include passing state tests, holding a degree in the subject area, and completing coursework (Putnam & Walsh, 2021). Research on teacher certification itself is inconclusive (Allen, 2003; National Research Council, 2010; Wilson & Youngs, 2005). Only modest positive relationships between teacher licensure exam scores and student achievement have been found (Clotfelter et al., 2007; Goldhaber, 2007). The predictive validity of licensure exams is unknown (Wayne & Youngs, 2003; Wilson & Youngs, 2005). Similarly, the predictive validity of performance evaluations, such as the Educative Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA) has not been established; more research is needed to determine the impact of edTPA scores on a teacher’s eventual performance (Chung & Zou, 2021).

Stronge and Hindman (2006) have argued that a teacher’s application materials can provide a measure of their content knowledge, certification status, teaching experience, knowledge of teaching and learning, and verbal ability. These materials are a good starting point for deciding which teacher candidates to move forward in the hiring process.

Within licensure, test pass rates and state-level recommendations may not be helpful indicators. Teacher license test pass rates generally are low. Most states set cut scores at or below the national median scores, resulting in high pass rates; for example, the pass rate in 2008–2009 was 95% (U.S. Department of Education, 2011). State-level approval processes to recommend teachers for licensure vary and are rarely evidence based (National Research Council, 2010; Wilson & Youngs, 2005).

[B head]Does Alternative Training Versus Traditional Certification Matter?

Constantine et al. (2009) reviewed teachers trained through alternative and traditional routes. The groups of teachers were comparable in their test scores and demographic data. There was no statistically significant difference in performance between students of teachers who had completed alternative certification programs and those who had completed traditional programs. There was no evidence that more teacher training coursework was associated with greater effectiveness in the classroom.

Additional studies found no difference between traditionally trained and alternatively trained teachers in terms of teacher performance or student outcomes; however, because alternatively trained teachers often stay for only 2-years, these studies examine teachers in their first years of teaching (Bos & Gerdeman, 2017; Constantine et al., 2009).

Also, because of the a lack of significant difference between alternatively and traditionally trained teachers, districts may want to partner with alternative certification programs, such as Teach For America (TFA), as they increase the teacher candidate pool overall and recruit teachers specifically for high-needs areas (See et al., 2020).

[B head]What Hiring Processes Are Most Effective?

The hiring process is an information exchange in which teachers and schools learn about each other (Liu & Johnson, 2006). Districts can take either a centralized or decentralized approach to hiring.

In centralized hiring, most of the work takes place at the district level and new teachers are assigned to schools; typically, it relies heavily on standardized procedures and interview protocols (Wise et al., 1987). The downside of a centralized approach is that it doesn’t consider the specific needs of individual schools, or the teacher characteristics that would make a particular teacher effective in a particular school (Liu & Johnson, 2006). Teachers who go through centralized hiring agree to work for the district, not an individual school.

In decentralized hiring, principals exert most of the control over hiring teachers for their individual schools. Decentralized hiring practices allow for more interaction between the school and the teacher. This allows for a better match between teachers and specific positions, school needs, and school culture. Principals and teachers decide which teacher qualifications to prioritize, design their own interview activities and questions (Wise et al., 1987). Decentralized hiring provides more connection between teachers and schools, allowing for a better information exchange between the two.

Many districts are somewhere in the middle between completely centralized and decentralized, with the district and the school each doing some of the work of hiring (Wise et al., 1987). For example, early hiring processes, such as screening and applications, might be done through the central office, while interviews might be conducted at the school.

Liu and Johnson (2006) examined how teachers in four states (California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Michigan) were hired and how those practices led to matches between teachers and schools. They identified hiring as a two-way process with teachers and schools learning about each other. A random sample of 486 first- and second-year teachers was surveyed across the four states. The majority of new teachers were hired through school-based processes rather than centralized district processes, and often teachers had limited interaction with school personnel during the hiring process. The researchers found the hiring process to be “information poor.” Many new teachers were hired late; more than one third of teachers in California and Florida were hired after the school year had begun.

In their study, Liu and Johnson found that new teachers had limited interactions with school-based personnel during the hiring process. While most teachers met with the principal, few met with other teachers, department chairs, students, or parents. Having information from a variety of school stakeholders can give teachers a better sense of what working in that school will be like. A lack of that information may lead to unmet professional expectations, which may contribute to ineffectiveness, dissatisfaction, and turnover.

Bruno and Strunk (2018) studied a teacher screening system in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) that connected applicant records with student and teacher-level data. A teacher candidate’s performance during screening was significantly predictive of an applicant’s eventual employment at LAUSD and a teacher’s later evaluation outcomes, attendance, and student achievement results. Teacher candidate’s performance during the application process was not predictive of mobility or retention. Screening measures include an interview, sample lesson, writing sample, references, GPA score, subject matter licensure exams, background, and preparation. How teacher candidates performed on their sample lesson was related to subsequent value-added contributions to student achievement and teacher evaluation outcomes. References, GPA scores, and subject matter knowledge scores were also associated with teacher evaluation outcomes and attendance.

The benefit of interviews. Of all screening measures, an interview provides an opportunity to integrate all the sources of information about a teacher, and to collect additional information about how the teacher thinks, communicates, and approaches their work. Behavior-based interviewing uses specific questions based on skills, background, and experience to assess a candidate’s competency (Clement, 2008). The supposition is that how people handled situations in the past will predict how they handle similar situations in the future (Deems, 1994). Behavior-based questions require candidates to discuss previous situations and problems, and are open ended. For example:

- Describe a situation when…

- Describe how you implemented…

- Describe a way to teach…

- Tell me about a typical lesson…

Questions about skills that are important to the principal can be created; for example, “Share an example of positive communication,” to gauge a candidate’s communication skills (Clement, 2008). When using behavior-based questions, interviewers must have criteria, such as a rubric or checklist, for judging a candidate’s response (Clement, 2008; Stronge & Hindman, 2006).

[A head]Cost of Teacher Selection

The cost to districts and schools depends on the processes put in place and the resources expended. One way of thinking about this, as outlined by Selected, a third-party hiring company, is to focus on recruitment costs (Thorson & Tam, 2020). To that end, the equation to gauge the cost of teacher selection in a district is as follows:

Cost per hire = (recruitment team salaries + third-party tools) ÷ number of teachers hired

Although the inputs may vary dramatically between districts, the actual cost per hire may be relatively similar. More research is needed to better understand how recruitment processes impact the cost per hire across districts and type of teacher candidate (e.g., elementary school teacher vs. special education teacher), and how recruitment costs change over time.

[A head]Recommendations for Teacher Selection

Ultimately, successful teacher selection depends on the supply of high-quality teachers and the processes in place to match those candidates with schools.

On the federal and state level, the following measures are helpful:

Address disincentives. Policies and communication must address disincentives to teaching, including low salary, lack of respect, and unfavorable working conditions (Bill et al., 2022).

Provide budgets early. State policy makers should provide budgets as early as possible to allow districts to determine staffing levels; unions can help by revisiting contract provisions regarding teacher selection timelines.

At the district level, often where restraints are placed on hiring (e.g., collective bargaining agreements, predicted staffing, budget), the following recommendations can support teacher selection:

Start early. The hiring process should begin as early as possible to allow for information-rich hiring (Liu & Johnson, 2006).

Let districts help screen applicants. Some hiring decisions can be made at the district level to provide a more information-rich hiring process at the school level (Liu & Johnson, 2006). For example, applicant screening can be centralized.

Screen applications for baseline information. School personnel can review applications for qualities of effective teachers, for example, strong content knowledge and preparation (Darling-Hammond & Youngs, 2002; Stronge, 2002). Screeners can look at a candidate’s major or minor in the subject taught and instructional methods courses taken in college for indicators of content knowledge and preparation.

Structure interviews to draw out effective teacher qualities. Administrators should be clear on what they want in a teacher and how they will recognize those qualities in a candidate. Predetermined interview questions can be asked in a prescribed order so the team has a clear idea how a candidate fits into the domains of teaching (Darling-Hammond & Youngs, 2002; Stronge, 2002). Behavior-based interview questions can provide information about how candidates will approach situations, and give information about skills that are important to the interviewer (Clement, 2008).

Provide opportunities for connection. Plan for teacher candidates to have interactions with school-based personnel, including other teachers, department heads, students, and parents (Liu & Johnson, 2006).

Consider alternatively certified teachers. These teachers can boost the candidate pool for districts. However, the same process and practices should be in place to vet them as are used to vet traditionally trained teachers.

[A head]Conclusion

Teacher selection is a primary function of school districts. Hiring the right teachers who have the capacity to be high-quality educators, shapes schools and student achievement in tangible and intangible ways. Focusing on understanding the qualities that make for great teachers, using behavior-based interviews, and connecting potential candidates with schools to get the “right fit” are all ways to maximize teacher selection practices in schools.

Citations

Allen, M. (2003). Eight questions on teacher preparation: What does the research say? A summary of the findings. Education Commission of the States.

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Efficient and effective teaching. Guilford Publications.

Babu, S., & Mendro, R. (2003, April 21–25). Teacher accountability: HLM-based teacher effectiveness indices in the investigation of teacher effects on student achievement in a state assessment program. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), Chicago, IL. https://www.dallasisd.org/cms/lib/TX01001475/Centricity/Shared/evalacct/research/articles/Babu-Teacher-Accountability-HLM-Based-Teacher-Effectiveness-Indices-2003.pdf

Bill, K., Bowsher, A., Malen, B., Rice, J. K., & Saltmarsh, J. E. (2022). Making matters worse? COVID-19 and teacher retention. Phi Delta Kappan, 103(6), 36–40. https://kappanonline.org/covid-19-teacher-recruitment-bill-bowsher-malen-rice-saltmarsh/

Bos, H., & Gerdeman, D. (2017, May 4). Alternative teacher certification: Does it work? American Institute for Research. https://www.air.org/resource/alternative-teacher-certification-does-it-work

Bruno, P., & Strunk, K. O. (2018). Making the cut: The effectiveness of teacher screening and hiring in the Los Angeles Unified School District (Working Paper 184). National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. https://caldercenter.org/publications/making-cut-effectiveness-teacher-screening-and-hiring-los-angeles-unified-school

Chung, B. W., & Zou, J. (2021). Teacher licensing, teacher supply, and student achievement: Nationwide implementation of edTPA (EdWorkingPaper No 21-440). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai21-440.pdf

Clement, M. C. (2008). Improving teacher selection with behavior-based interviewing. Principal, 87(3), 44–47.

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). How and why do teacher credentials matter for student achievement? (Working Paper 12828). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w12828

Combs, E., & Silverman, S. (2018). The teacher pipeline: Recruiting and hiring practices that worsen the teacher shortage. Frontline Institute. https://www.frontlineinstitute.com/reports/leak-pipeline-recruiting-report/

Constantine, J., Player, D., Silva, T., Hallgren, K., Grider M., & Deke, J. (2009). An evaluation of teachers trained through different routes to certification, final report. (NCEE 2009-4043). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Science, U.S. Department of Education.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of the Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143.

Cruickshank, D. R., & Haefele, D. (2001). Good teachers, plural. Educational Leadership, 58(5), 26–30.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Youngs, P. (2002). Defining “highly qualified teachers”: What does “scientifically-based research” actually tell us? Educational Researcher, 31(9), 13–25.

Deems, R. S. (1994). Interviewing: More than a gut feeling. American Media Publishing.

Gershenson, S., Hansen, M. & Lindsay, C.A. (2021). Teacher diversity and student success: Why racial representation matters in the classroom. Harvard Education Press.

Goldhaber, D. (2007). Everyone’s doing it, but what does teacher testing tell us about teacher effectiveness? Journal of Human Resources, 42(4), 765–794.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analysis related to achievement. Routledge.

Ingersoll, R. (2003). Is there really a teacher shortage? Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania. https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/133/

King, J., & James, W. (2022). Colleges of education: A national portrait. American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. https://aacte.org/2022/03/aactes-national-portrait-sounds-the-alarm-on-declining-interest-in-education-careers/

Knight, J. (2012). High-impact instruction: A framework for great teaching. Corwin Press.

Liu, E., & Johnson, S. M. (2006). New teachers’ experience of hiring: Late, rushed, and information-poor. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(3), 324–360. http://www.uaedreform.org/site-der/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Liu-2006-EAQ-New-teachers-experiences-of-hiring.pdf

Marzano, R. J., Marzano J. S., & Pickering, D. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research based strategies for every teacher. ASCD.

National Research Council. (2010). Preparing teachers: Building evidence for sound policy. National Academies Press. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12882

Peske, H. G., Liu, E., Johnson, S. M., Kauffman, D., & Kardos, S. M. (2001). The next generation of teachers: Changing conceptions of a career in teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(4), 304–311.

Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educational Researcher, 50(5), 325–327.

Putnam, H., & Walsh, K. (2021). Teacher licensure pass rates: Driven by data: Using licensure tests to build a strong, diverse teacher workforce. National Council on Teacher Quality. https://www.nctq.org/publications/Driven-by-Data:-Using-Licensure-Tests-to-Build-a-Strong,-Diverse-Teacher-Workforce

Remer, C. W. (2017). Educator policies and the Every Student Succeeds Act. Hunt Institute. http://www.hunt-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ESSA-Educator-Policies-The-Every-Student-Succeeds-Act.pdf

Sanders, W. L., & Rivers, J. C. (1996). Cumulative and residual effects of teachers on future student academic achievement. University of Tennessee Value-Added Research and Assessment Center. https://www.heartland.org/publications-resources/publications/cumulative-and-residual-effects-of-teachers-on-future-student-academic-achievement

See, B. H., Morris, R., Gorard, S., Kokotsaki, D., & Abdi, S. (2020). Teacher recruitment and retention: A critical review of international evidence of most promising interventions. Education Sciences, 10(10), 262.

States, J., Detrich, R., & Keyworth, R. (2012). Effective teachers make a difference. In Education at the Crossroads: The State of Teacher Preparation, 2, 1–46. The Wing Institute.

Steiner, E. D. & Woo, A. (2021). Job-related stress threatens the teacher supply: Key findings from the 2021 state of the U.S. teacher survey. RAND Corporation.

Stronge, J. H. (2002). Qualities of effective teachers. ASCD.

Stronge, J. H., & Hindman, J. L. (2003). Hiring the best teachers. ASCD. www.ascd.org/el/articles/hiring-the-best-teachers

Stronge, J., & Hindman, J. (2006). The teacher quality index: A protocol for teacher selection. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/books/the-teacher-quality-index?chapter=teacher-quality-and-teacher-selection

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L. & Carver-Thomas, D. (2019). Understanding teacher shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(35), 1–36.

Thorson, A., & Tam, W. (2020, May 5). Hiring yield and cost per (teacher) hire: The only recruitment metrics that matter. Selected. https://blog.getselected.com/2020/05/05/hiring-yield-and-cost-per-teacher-hire-the-only-recruitment-metrics-that-matter/

U.S. Department of Education. (2011). Preparing and credentialing the nation’s teachers: The secretary’s eighth report on teacher quality based on data provided for 2008, 2009, and 2010. https://title2.ed.gov/public/TitleIIReport11.pdf

Walberg, H. (1999). Productive teaching. In H. C. Waxman & H. J. Walberg (Eds.) New directions for teaching practices and research (pp. 75–104). McCutchan Publishing.

Walker, T. (2021, June 17). Educators ready for fall, but a teacher shortage looms. NEA Today.

Wayne, A. J., & Youngs, P. (2003). Teacher characteristics and student achievement gains: A review. Review of Educational Research, 73(1), 89–122.

Wenglinsky, H. (2002). How schools matter: The link between teacher classroom practices and student academic performance. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 10(12), 1–30.

Wilson, S. M., & Youngs, P. (2005). Research on accountability processes in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education (pp. 591–643). American Education Research Association.

Will, M. (2022, March 22). Fewer people are getting teaching degrees. Prep programs sound alarm. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/fewer-people-are-getting-teacher-degrees-prep-programs-sound-the-alarm/2022/03

Wise, A. E., Darling-Hammond, L., & Berry, B. (1987). Effective teacher selection: From recruitment to selection. RAND Corporation.