Principal Evaluation

Principal Evaluation PDF

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2021). Principal Evaluation Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-leadership-principal-evaluation

Principals influence student learning and achievement in strong but indirect ways, making them key contributors to school improvement efforts (Hallinger & Heck, 2010; Hitt & Tucker, 2016; Leithwood et al., 2010, 2020; Robinson et al., 2008; Supovitz et al., 2010; Viano et al., 2021). In fact, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires that every school be staffed with an effective leader (Fuller et al., 2017). Principals’ roles have become increasingly complex as they face heightened accountability pressures to improve student outcomes (Fuller & Hollingworth, 2014; Goldring et al., 2009) and the expectation to provide instructional leadership and leadership for equity rather than simply managerial competence (Davis et al., 2005; Grissom et al., 2021). Ensuring effective school leadership requires best practice in each phase of the principal development pipeline, from recruiting the right candidates to evaluating their performance and providing targeted and ongoing support throughout their careers.

Fitzpatrick et al (2011) noted that the fundamental purpose of evaluation is “the identification, clarification, and application of defensible criteria to determine an evaluation object’s value (worth or merit) in relation to those criteria” (p. 7). The purpose of principal evaluation is to use these criteria to assess a principal’s worth or merit (Fuller et al., 2015). Current practices grew out of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), No Child Left Behind (NCLB) waivers, Race to the Top (RTTT) funding, and the recent reauthorization of ESEA as ESSA, focusing on providing policies aimed at improving principals’ skills (Donaldson et al., 2020; Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs et al., 2021; Fuller & Hollingworth, 2015; Grissom et al., 2021).

Emphasizing principal evaluation is based on the theory of action that evaluation can be used for both summative and formative purposes to improve performance by increasing accountability and providing support through enhanced feedback and coaching, and targeted professional development opportunities (Donaldson et al., 2020). Recent principal evaluation systems strive both to evaluate principal performance and build leadership capacity (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016). However, while the teacher evaluation research base has increased substantially over the past two decades, principal evaluation has attracted much less attention in the research community (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016; Clifford & Ross, 2012; Davis et al., 2011; Donaldson et al., 2020; Goldring et al., 2009).

This review briefly describes the evolution of principal evaluation policies in the United States, discusses current commonly used evaluation systems in terms of purpose, components, processes, and consequences, and considers evidence-based strategies, best practice, and recommendations.

Principal Evaluation and Evolving Policy and Practice in the United States

Those designing and developing principal evaluation systems must address what to assess and how best to assess it (Donaldson, Mavrogordata, Dougherty, et al., 2021; Goldring et al., 2009). The what question involves identifying the standards and practices that constitute effective leadership, while the how question involves creating valid and reliable instruments and processes for comparing what principals do against standards (Grissom et al., 2018).

Historically, principal evaluation systems have not been designed to pay serious attention to either of these questions (Grissom et al., 2018). Prior to 2009 and the advent of RTTT and ESEA waivers, principal evaluation systems varied widely at both state and district levels, and most frequently lacked a research-based foundation for their implementation (Davis et al., 2011; Ginsberg & Berry, 1990; Ginsberg & Thompson, 1992). Commonly used types of evaluation were a simple checklist on which a supervisor rated the principal’s behaviors or traits in areas such as loyalty or time management, and a narrative, open-ended evaluation of performance (Lashway, 2003; Reeves, 2005). Very few principals found these evaluations useful or relevant in improving their job performance, and most did not receive actionable feedback from supervisors about specific behaviors that should be modified for improvement (Reeves, 2005). Additional research demonstrated that principals often felt that evaluations were subjective and political, were carried out inconsistently, and failed to account for contextual differences between schools (Davis & Hensley, 1999).

Most evaluation approaches were not connected to student outcomes, and “a principal could have the appropriate knowledge and skills or exhibit the ‘correct’ behaviors and be evaluated as effective regardless of school outcomes” (Fuller et al., 2015, p. 166). The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 ushered in increased adoption of high-stakes testing, and a number of states began requiring the inclusion of outcome measures of achievement, attendance, and graduation in principal evaluation (Clifford & Ross, 2012).

However, researchers questioned the validity of linking these outcomes to principal behaviors and competencies through the evaluation process (Goldring et al., 2009). Goldring and colleagues analyzed the content and usage of 65 district- and state-level principal evaluation systems across 40 states using a learning-centered leadership framework (Murphy et al., 2006) to determine the congruence between research-based effective leadership criteria and these instruments and evaluation practice. The learning-centered leadership framework includes leadership behaviors and school conditions that have been shown to lead to improvements in school performance; evaluation measures the extent to which the principal acts to ensure that these conditions are in place (e.g., quality instruction and rigorous curriculum) (Murphy et al., 2006). Goldring et al. (2009) found that principal evaluation systems often included instruments that lacked evidence of validity and/or psychometric properties (e.g., reliability) and were not linked to leadership standards; these systems most often failed to evaluate principals on key research-based leadership behaviors linked to student achievement, such as ensuring a rigorous curriculum and high-quality instruction.

Several comprehensive reviews of the literature over this period concluded that most evaluation systems (1) lacked reliability and validity and were frequently applied unevenly; (2) were only loosely linked to professional leadership standards; (3) lacked an evidence base of whether and how they improved practice; and (4) were developed around various performance criteria rather than school or student outcomes and often had mixed purposes, such as accountability versus improved practice (Clifton & Ross, 2012; Davis et al., 2011; Portin et al., 2006).

Several studies conducted over this period, however, also demonstrated that evaluation systems based on leadership standards and an emphasis on instructional leadership had the potential to produce more positive outcomes than those lacking this foundation. Kimball et al. (2009) randomly assigned principals in a large western U.S. school system to be evaluated using either a new standards-based system or the traditional system. They found through surveys and interviews that principals in the new system were more likely than their colleagues to report clarity about evaluation expectations, useful feedback and support for improvement, and satisfaction with their evaluation; however, they also reported conflicts with competing messages from other sources defining performance expectations in alternative ways. Sun and Youngs (2009) analyzed principal evaluation purposes, focus, and assessed leadership activities in districts in Michigan and their relationship to principal behaviors characteristic of learning-centered leadership (Murphy et al., 2006. When evaluation systems included purposes (e.g., principal professional learning) and practices (e.g., a focus on school goal setting, teacher professional learning, and close monitoring of student learning) consistent with instructional and learning-centered leadership, principals were more likely to engage in leadership behaviors that have been shown to support student learning (Sun & Youngs, 2009).

Grissom et al. (2018) noted that “growing national attention to the importance of school leadership, coupled with a new focus on increasing the rigor of teacher evaluation as a means of improving teacher effectiveness, has led to widespread reform of principal evaluation in recent years” (p. 449). More recent evaluation systems in use since RTTT and ESEA waivers have addressed some of the weaknesses cited in previous research, and states’ evaluation of principals has changed dramatically over the past decade (Fuller et al., 2015). RTTT and ESEA waivers have sought to more closely link the work of principals to the improvement of student learning, and encouraged the use of systems that measured performance in accordance with on evidence-based school leadership behaviors and student achievement (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021). Both policies require that principals be evaluated using multiple measures and incorporate student achievement/academic growth measures (U.S. Department of Education, 2009, 2011); however, most of the details, such as how much weight is given to academic performance scores in the final summative rating, are left up to states to determine (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021).

Many of the recent state systems focus on enhancing principals’ instructional leadership and are based on the assumption that evaluation can improve performance by instilling accountability and enhancing feedback and coaching for principals (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Dougherty, et al., 2020; 2021). Fuller and colleagues (2015) studied principal evaluation policies in all 50 states and reported that the primary purpose of these policies in more than three quarters of states was to support professional growth. In addition, policies in more than two thirds of states linked evaluation results to principal compensation, promotion, or dismissal. Most states incorporated student academic performance and approximately one quarter also included measures of teacher quality and/or retention, school climate, and teacher working conditions. Overall, states had adopted more diverse measures of principal performance that were more closely tied to student and teacher outcomes (Fuller et al., 2015).

Current Principal Evaluation Systems and Research on Best Practice

Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Dougherty, et al. (2021) conducted a more recent state policy scan of principal evaluation in the United States, and summarized policies in place across all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Results from this study are discussed in the sections below related to the purposes, components, processes, and consequences of principal evaluation.

Purposes of Evaluation

Research suggests a shift in current practice from evaluation as strictly a compliance activity conducted infrequently and with little attention to the purposes of the evaluation, to how information produced by the evaluation process can be used constructively. Burkhauser et al. (2013) defined common purposes of principal evaluation systems as “clarifying expectations for practices in which principals should engage; providing formative feedback to help principals improve their practice; promoting state or district goals (particularly around improvement of teaching); [and] supporting decisions about hiring, placement, dismissal, and compensation” (p. 3).

Evaluation purposes then guide selection of multiple evaluation measures, and system designers must consider how to combine data from these measures into overall evaluation scores. When evaluation systems are intended to produce summative scores to hold principals accountable for performance, high levels of validity and reliability are particularly important; if the purpose is only to provide formative feedback for improvement, these issues are less of a concern (Burkhauser et al., 2013). For either type of data to have its intended impact, principals must perceive evaluation systems to be reasonable, fair and accurate (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011; Grissom et al., 2015). Otherwise, principals may ignore or subvert the evaluation information, or in some cases attempt to “game the system” by manipulating data collected to avoid negative evaluation consequences or to gain rewards (Kane & Staiger, 2002).

States have, in essence, turned to a two-pronged approach that emphasizes results-based accountability and principal development as purposes for the evaluation (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021; Scott, 2013). The notion of principal accountability has shifted generally from an assessment of how well principals run their school buildings and how much they are liked by teachers, toward holding principals responsible for demonstrating leadership standards of practice and attaining student outcome benchmarks (Donaldson et al., 2020). Most states have delegated authority for principal evaluation to the district level, and most (84%) allow districts to create their own systems provided they are consistent with state policy requirements (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021). In addition, 61% of states require annual evaluations of all principals (both probationary and nonprobationary), and slightly more than half (53%) specify that this evaluation be conducted by the superintendent (or designee) or other district administrators such as supervisors (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021). Approximately half of states require some type of principal evaluator training. A lack of principal evaluator training can be particularly problematic when principals are evaluated in high-stakes systems (Goff et al., 2016).

As noted previously, designers of principal evaluation systems must consider the what in terms of the components that should be measured and how much each component should contribute to summative evaluation scores, and the howin terms of the processes used to capture data (Goldring et al., 2009). Also important are the consequences of the evaluation, which include the next steps for using the information collected for decision making about the principal’s employment status or compensation, as well as professional development to support improvement (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Dougherty, et al., 2021). Each of these areas and current related research are discussed below.

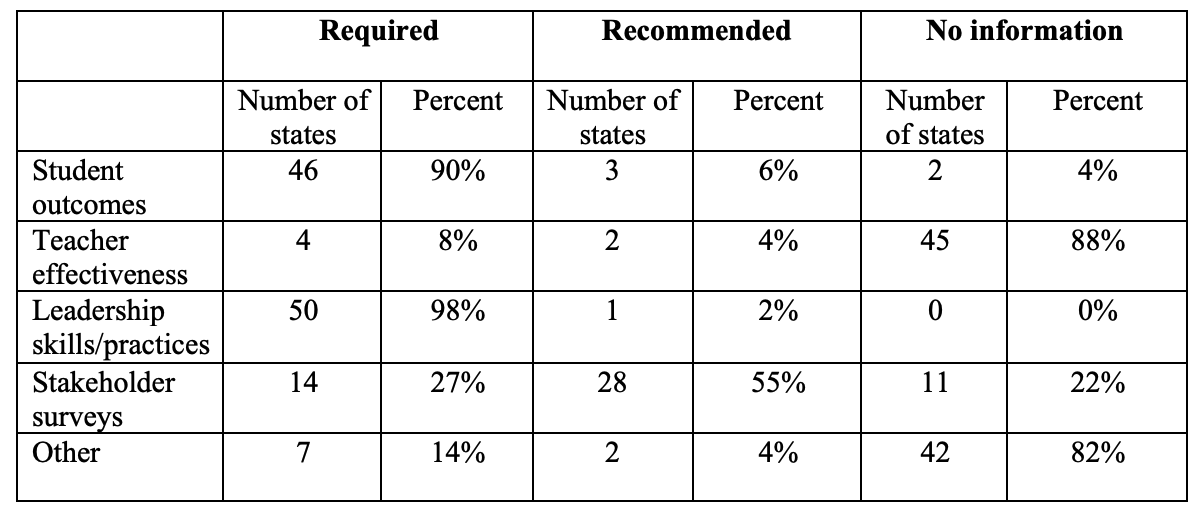

Evaluation Components

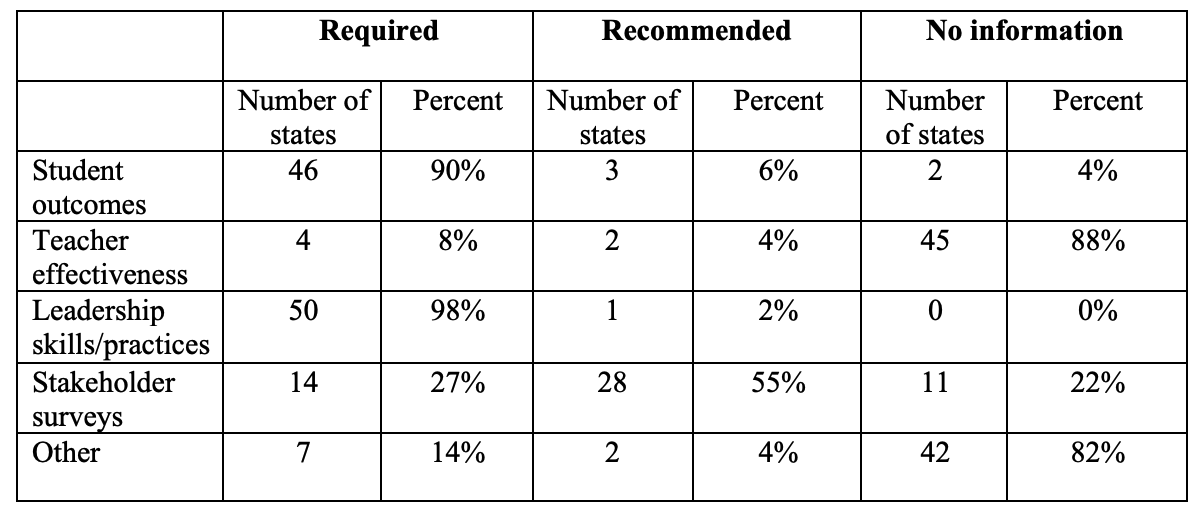

Table 1 highlights selected results of the Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021) study in terms of the components of state principal evaluation systems. They showed that almost all states required the inclusion of leadership skills and practices (98%) and student outcomes (90%) components in their evaluation systems; however, only slightly more than half actually specified the weight of each of these components in the principal’s final summative rating. The modal (most frequently occurring) weight for each was 50% (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021). For example, in Tennessee’s system of principal evaluation, 50% involved measures of student achievement (35% based on value-added schoolwide measures of academic growth, and 15% based on additional achievement measures agreed upon by principal and evaluator), and 50% consisted of subjective scores assigned by an evaluator (typically a principal supervisor) using a leadership standards-based rubric (Grissom et al., 2018).

Table 1. Components of principal evaluation systems across states and Washington, D.C.

Adapted from Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021), p. 351. Some percentages add up to more than 100 due to rounding errors or to variables being partly required or partly recommended in some states. Weights for each component are not included in this table.

Stakeholder surveys of principal performance by teachers, students, parents, and community members were required by just 27% of states, but recommended by more than half (55%); however, few states (8%) included these data independently in the final summative evaluation. The use of stakeholder surveys is thought to contribute to a “360-degree” comprehensive view of principal performance and is increasingly recommended in the literature as a component of evaluation systems (Goldring, Mavrogordato, et al., 2015).

An example of a 360-degree survey is the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED), a principal evaluation tool focused on instructional leadership and leadership for learning that synthesizes feedback from surveys of principals, principal supervisors, and teachers to provide an overall principal performance score (Murphy et al. 2006; Porter et al., 2010). This standards-based instrument “measures critical leadership behaviors for the purposes of diagnostic analysis, progress monitoring, and summative evaluation” (Goldring, Cravens, et al., 2015, p. 179). VAL-ED has undergone significant research to confirm its psychometric properties (reliability and validity), and has been used extensively as a component of several large-scale initiatives that address principal evaluation (e.g., Goldring et al., 2020). It was used in one study as a component of a comprehensive teacher and principal feedback system that produced significant enhancements in in instructional leadership and teacher-principal trust (Garet et al., 2017).

Fuller et al. (2015) found that many states used school climate/teacher working conditions surveys in evaluation systems with high-stakes consequences; they urged caution with interpretation and use for high-stakes decision making due to a lack of survey instrument validation and varying response rates across schools. The research by Donaldson, Mavrogordato and Youngs, et al (2021) showed that just 12% of states required or recommended that measures of teacher effectiveness be used to evaluate principals, which represents a decrease from the findings of Fuller et al. (2015) in which 22% of states featured teacher quality, effectiveness, and/or retention.

These findings are generally consistent with other literature suggesting that districts have adopted new principal evaluation systems that include measures of professional practice and student achievement growth (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016; Fuller et al., 2015). Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021) noted that changes to the components included in principal evaluation systems showed a promising shift toward more research-based approaches and addressed some of the weaknesses in principal evaluation described previously.

Newer systems are more likely to be based on standards for effective leadership practice (typically rated by principal evaluators/supervisors using rubrics that address standards-based practices), such as the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL), that link principals’ actions with desired outcomes (Clifford & Ross, 2012; National Policy Board for Education Administration [NPBEA], 2015; Anderson & Turnbull, 2016). PSEL standards “guide professional practice and how practitioners are prepared, hired, developed, supervised and evaluated” (NPBEA, 2015, p. 2). Principal leadership standards, which are critical for principal evaluation and development, have evolved over time to emphasize principals as instructional leaders in their buildings (Canole & Young, 2013; Hackman, 2016). PSEL standards address key leadership areas including: (1) curriculum, instruction, and assessment; (2) equity and cultural responsiveness; and (3) building the professional capacity of school personnel (NBPEA, 2015). Standards-based leadership evaluation is considered to be a more valid assessment of principal effectiveness as it typically incorporates multiple measures to enhance validity, requires evaluator training, and can reduce evaluator subjectivity (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016; Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Dougherty, et al., 2021; Kimball & Milanowski, 2009; Kimball et al., 2009).

While principal effectiveness has been shown to influence student achievement (Branch et al., 2012; Hitt & Tucker, 2016; Liebowitz & Porter, 2019; Robinson et al., 2008), the legitimacy of and the manner in which to incorporate student outcomes in the form of achievement/growth scores in principal evaluation systems are currently areas of debate, with mixed results from studies (Chiang et al., 2016; Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021; Grissom et al., 2015; Fuller et al., 2015). Districts vary widely in the way they use student outcomes to evaluate principals (Anderson & Turnbull, 2015; Herman & Ross, 2016). In the early part of the past decade, Tennessee, Florida, and Louisiana enacted legislation that required districts to include student outcomes in principal evaluation systems (Grissom et al., 2015). Many of these systems involved the use of value-added student growth scores to document principal performance; however, researchers have noted the difficulties with their use and interpretation:

For example, disentangling the impact of the educator from the long-run impact of the school presents particular difficulties for principals because there is only one principal at a time in each school. Moreover, it is difficult to choose how much of the school’s performance should be attributed to the principal or instead to the factors outside of the principal’s control. Should, for example, principals be responsible for the effectiveness of teachers that they did not hire? From the point of view of the school administrator whose compensation level or likelihood of keeping his or her job may depend on the measurement model chosen, thoughtful attention to these details is of paramount importance. (Grissom et al., 2015, p. 4)

Several studies have suggested that student achievement value-added growth scores may be strongly related to variables outside the principal’s control, such as student demographics (Chiang et al., 2016; Fuller & Hollingworth, 2014; Grissom et al., 2015; Henry & Viano, 2016; Herman & Ross, 2016), suggesting concerns about whether they are valid measures of principal performance. Chiang et al. (2016) researched principals’ effects on student achievement growth using longitudinal data on the math and reading outcomes of fourth- to eighth-grade students in Pennsylvania, and concluded that the school value-added was a very poor predictor of principals’ persistent level of effectiveness. Herman and Ross (2016) analyzed New Jersey’s principal performance system and concluded that the proportion of principals ranked as highly effective was lower among those who were evaluated using median student growth percentiles compared with peers who were evaluated using other measures such as whether they attained their own professional goals for student achievement.

In addition, achievement growth measures were associated with student socioeconomic status in a way that suggested they might be biased against principals working in schools with high percentages of students from low-income families. Grissom et al. (2018) studied principal evaluation in Tennessee, finding that schools with larger numbers of low-income students tended to be led by principals with lower performance ratings, and that bias against principals leading high-poverty schools was likely in the evaluation system. In a pilot study of the Framework for Leadership (FFL) evaluation system piloted in Pennsylvania, researchers found that higher FFL scores were associated with greater value-added scores; however, the relationship was observed only for principals at the middle school level and only for math but not reading or writing scores (McCullough et al., 2016).

These mixed results regarding value-added student achievement scores as a measure of principal performance may be contributing to policy changes. A recent report by the National Center on Teacher Quality ([NCTQ], 2019) found that 34 states had made progress toward more comprehensive principal evaluation by including student growth data over the past decade, but that 10 states had retreated from requiring these data from 2015 to 2019. An additional trend is for states to encourage districts to link summative principal evaluation results with efforts to more closely supervise principals to support their growth. Several studies on newer principal evaluation systems have found that supervisors are engaging principals in continuous improvement cycles through goal setting based on summative evaluation data, and providing mentoring and coaching to support principals as instructional leaders (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016; Kimball et al., 2015). Additional review of effective principal supervisor practice in principal evaluation is provided in the next section.

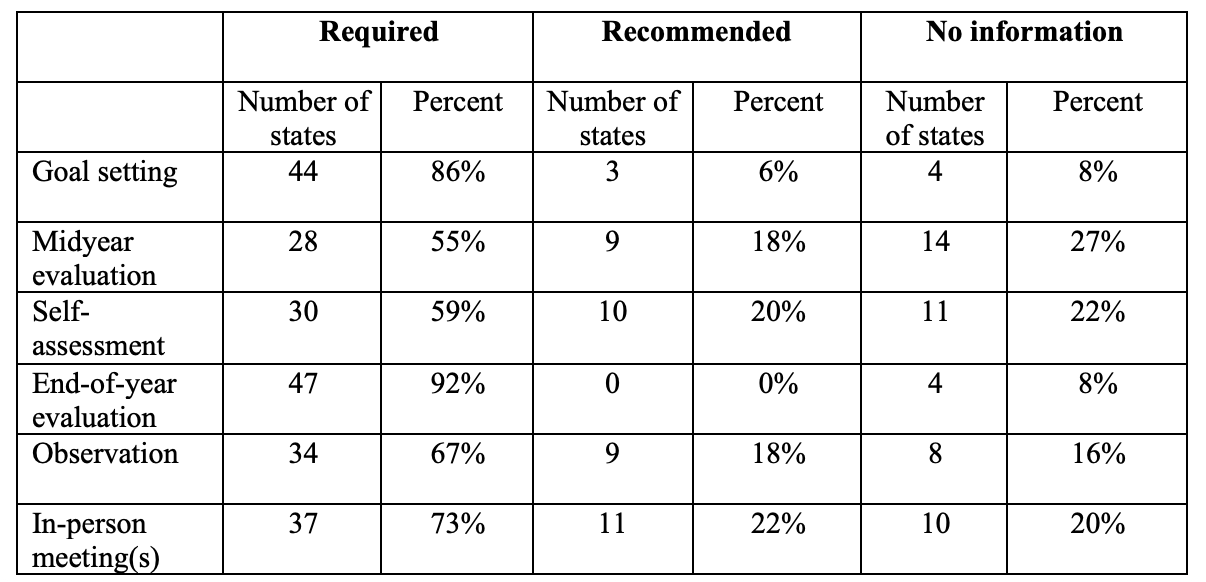

Evaluation Processes

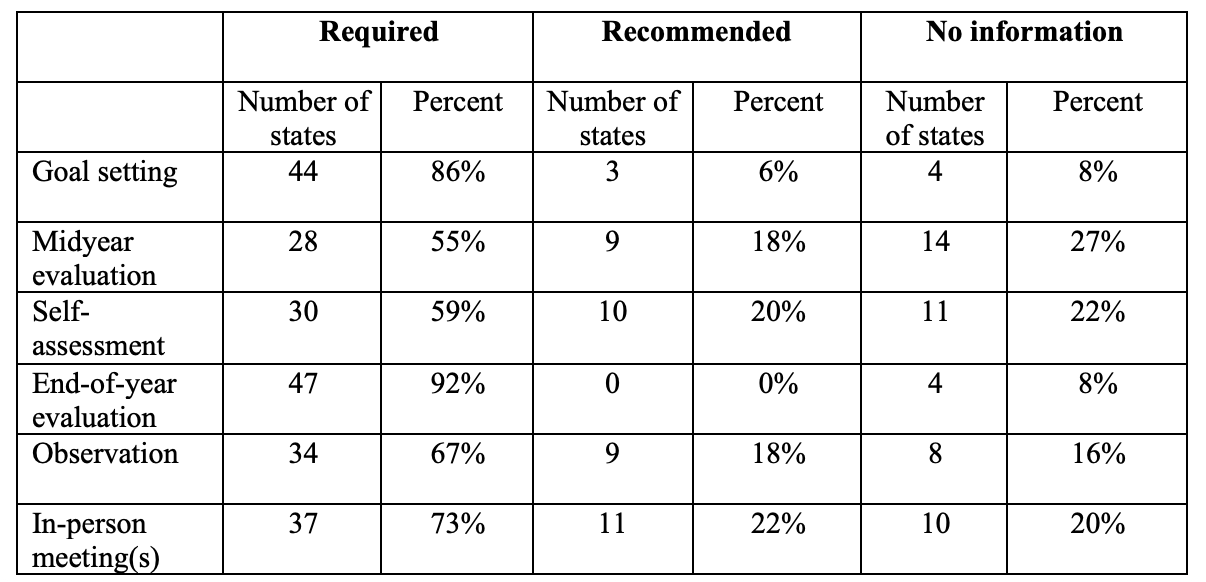

Table 2 includes results from recent state policy analysis research by Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021) on principal evaluation processes in place across the country. These results show that in contrast to the traditional process of implementing at most a single end-of-year evaluation, which principals often did not view as useful for improvement, most states now either require or at least recommend additional evaluation processes supported by research. Of note, almost all states (92%) either recommended or required principals to engage in goal setting/improvement plan development as part of the evaluation system, and 79% recommended or required principal self-assessment. Nearly three quarters of states also required or recommended more frequent principal monitoring by supervisors/evaluators through a midyear evaluation, allowing for formative feedback during the school year to guide principals’ efforts to improve. In addition, two thirds of states required that principals be observed in action, and nearly three quarters required in-person follow-up meetings to discuss evaluation results. Further inspection of the types of in-person meetings revealed that they focused on goal setting (49% required), pre-observation meetings (12% required), post-observation meetings (25% required), midyear meetings (45% required), end-of-year meetings (65% required), and other topics (12% required) (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021).

Table 2. Processes of principal evaluation systems across states and Washington, D.C.

Adapted from Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021), p.351. Some percentages add up to more than 100 due to rounding errors or to variables being partly required and partly recommended in some states.

These results show that newer principal evaluation systems not only include multiple types of data on principal performance but also engage principals and supervisors together more actively and frequently in the evaluation process. As noted previously, traditional evaluation systems often included infrequent evaluations and lack of substantive feedback from supervisors to support principals’ growth (Reeves, 2005). Research suggests that more frequent formative feedback provided throughout the year has the potential to improve performance when combined with targeted professional learning such as mentoring or coaching (Burkhauser et al., 2013; Grissom et al., 2018). Experts in the field of school leadership evaluation argue that principal self-assessment and goal setting can support principals’ intrinsic motivation (Locke & Latham, 2002), and research demonstrates that principals believe that goal-setting, self-reflection, and constructive performance feedback are valuable to them professionally (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016; Chacon-Robles, 2018; DeMatthews et al., 2020; Sanders, 2008).

Several recent comprehensive studies have addressed major principal evaluation reforms. The Principal Pipeline Initiative (PPI), conducted in six urban districts, sought to develop a strong cadre of principals, in part through improvements to principal evaluation that included measures of student achievement growth and principal practice (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016). Novice principals were evaluated using systems that identified strengths and weaknesses linked to tailored support and professional learning; district leaders did not use evaluations to weed out ineffective principals, taking care not to increase already high turnover. The principal evaluator role was redefined to include quality coaching, and PPI principals were provided with additional supports such as university partnerships and formal training targeted to improving weaknesses. Results showed that evaluators focused less on evaluating compliance with district priorities and more on helping the principal become a more effective instructional leader (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016). The researchers also found that principals’ perceptions of their evaluator/supervisor were generally positive and grew more positive across the several years of the study; ratings of mentors and coaches as sources of support were even more positive. Principals also expressed limited satisfaction with the professional learning they received (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

Kimball et al. (2015) investigated another major principal evaluation reform developed through Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF) monies in several large districts throughout the country. The new evaluation system established individual professional development plans that included principal self-assessments and a performance dialogue with the principal supervisor who had received intensive training and support to conduct evaluations and provide coaching and mentoring. The evaluation cycle included initial goal setting, feedback and coaching throughout the cycle, planning, and using results to link the principal to professional development. Kimball and colleagues concluded that the new evaluation systems were more complex and demanding than previous approaches, and placed a spotlight on the importance of well-trained supervisors who could implement the new evaluation tools with fidelity. They further noted that large districts were beginning to reduce the supervisor-to-principal ratio, and also documented a shift toward supplementing evaluation with mentoring and coaching by experienced, retired principals or by a superintendent with close relationships to the district’s principals.

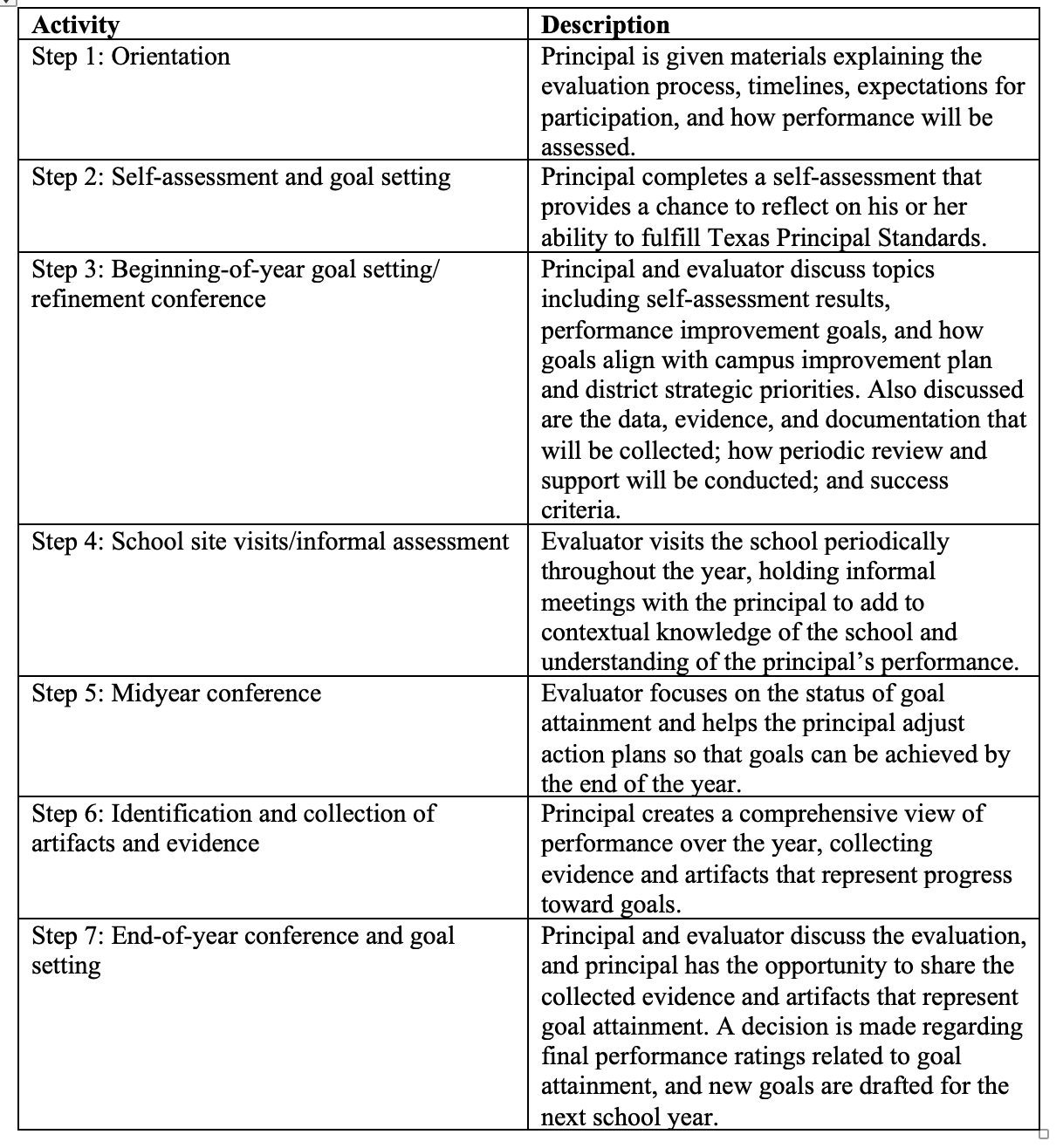

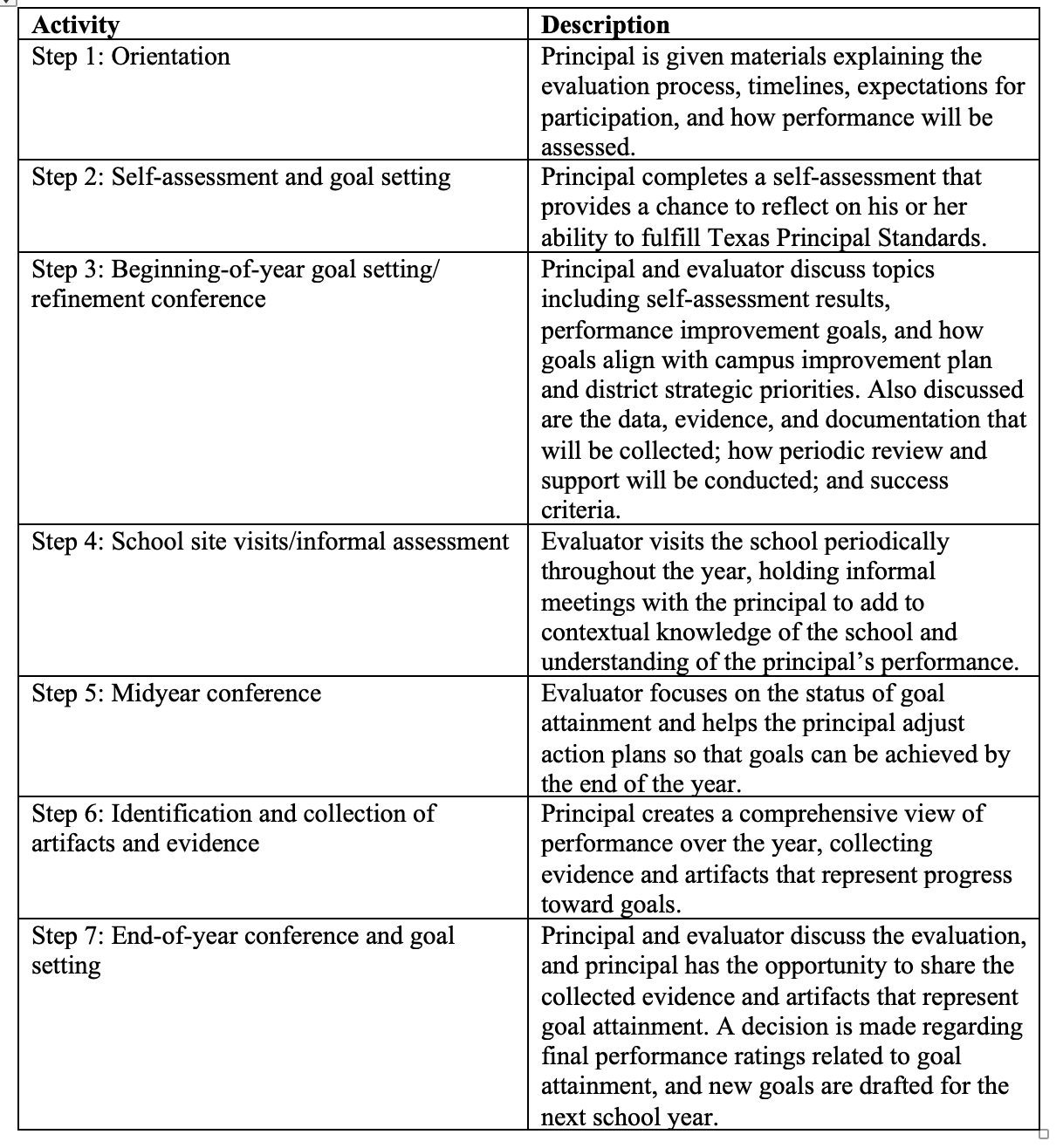

DeMatthews et al. (2020) examined principals’ perceptions of the Texas Principal Evaluation and Support System (T-PESS), which incorporates many of these research-based practices within a cycle of continuous improvement. The aim of their qualitative study was to determine how veteran principals understood and experienced the system, and which features they found most useful to their professional growth and which posed barriers. The T-PESS evaluator uses a standards-based rubric with the principal annually in a seven-part chronological evaluation process (Texas Education Agency, 2019); see Table 3.

Table 3. Texas Principal Evaluation and Support System (T-PESS)

Adapted from DeMatthews et al. (2020).

Principals reported that self-assessments, goal setting, and ongoing evaluator coaching and relationships were supportive of enhanced leadership capacity. Goal setting also focused on a single goal; principals believed one goal was more doable than multiple goals considering the complexity and ever-changing challenges of a principalship. Each principal reported a trusting relationship with the evaluator, which was important for the problem-solving/coaching aspects of the evaluation system (DeMatthews et al., 2020). However, similar to findings in other research (Goldring, Mavrogordato, et al., 2015; Zepeda et al., 2014), principals also reported that it was difficult for any evaluation to accurately reflect their performance given unique school contexts that included varying levels of teacher capacity, school culture, and community rapport. Principals may experience cognitive dissonance, for example, when their self-assessment of leadership competencies conflicts with multisource feedback from other stakeholders such as teachers (Goldring, Mavrogordato, et al., 2015).

DeMatthews et al (2020) also noted that “principals felt that the district provided burdensome and useless bureaucratic work and had not sufficiently developed a system of comprehensive leadership development, which meant principals had limited time and were expected to take the primary responsibility in their own professional development while also leading their school” (p. 21). Zepeda et al (2014) investigated a superintendent’s experiences with a high-stakes principal evaluation through case study research, and uncovered tensions, including difficulties understanding discrepancies between actual principal performance (e.g., measured by classroom walk-through observation data collected by the evaluator) and school performance (e.g., student achievement data), considerations of the type of school inherited by the principal (e.g., high vs. low performing) and the length of time in the principalship compared with outcomes (e.g., how long is enough to see positive results). Zepeda and colleagues noted the importance of open communication lines between evaluator and principal to individualize evaluations or, at the very least, to accurately reflect the local school context.

Shifting Role of Principal Supervisor in Principal Evaluation

Findings from these studies highlight the importance of the principal–evaluator relationship for ensuring that evaluations are fair and accurate, and that they result in performance improvements. The role of the principal supervisor has generally shifted from ensuring administrative compliance with district policies to supporting principals’ growth as instructional leaders (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016; Grissom et al., 2018; Rogers et al., 2019; Rubin et al., 2020). Rogers et al. noted several challenges for supervisors attempting to implement meaningful and valid principal evaluations:

- Capacity: Many supervisors may lack the knowledge and skills to identify and evaluate principals’ instructional leadership, making it unlikely that they can provide valid and actionable feedback.

- Data: Supervisors need timely, reliable, and relevant data on school and teacher performance; sophisticated systems to monitor and review ongoing principal progress may not always be available.

- Time: There must be adequate time to conduct evaluations at regular intervals during the school year, along with accompanying workload structures and logistical supports.

Standards for principal supervisors, which were developed for the first time in 2015 (Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO], 2015), state that “the primary role of the principal supervisor is to support and improve principals’ capacity for instructional leadership…[and] instructional leadership…is the focus of four of the eight standards” (p. 8). Principal supervisors are also expected to “coach and support individual principals and engage in effective professional learning strategies to help principals grow as instructional leaders” (p. 8). Research shows that principals need ongoing, high-quality in-service training and support, such as mentoring and coaching programs, which are critical in developing and keeping effective principals (Coggshall, 2015; Sutcher et al., 2017). This new role also requires an understanding of adult learners and their developmental needs (Mendels, 2017). The standards also state that a principal supervisor must be ready to “shift from being a coach to a supervisor as necessary to push the learning of the principal” (CCSSO, 2015, p. 16). Rogers et al. (2019) noted that this dualistic role of evaluator and coach “may create conflict because it requires supervisors to engage in both the development and judgment of principals, a concern that is sometimes raised in studies of principal support and mentorship” (p. 444).

The Wallace Foundation recently implemented the Principal Supervisor Initiative (PSI) to redefine the role of the principal supervisor in six urban districts across the country (Goldring et al., 2020). It “aimed to help districts overhaul a position traditionally focused on administration, operations, and compliance to one dedicated to developing and supporting principals to be effective instructional leaders in their schools” (Goldring et al., 2020, p. xv). The initiative also reduced the number of principals overseen by supervisors, trained supervisors to enhance their capacity to support principals, developed succession planning systems to develop and train new supervisors, and strengthened central office structures to support and sustain supervisors’ changing roles (Goldring et al., 2020). Findings included improvements to principals’ perceptions of their work with their supervisor and their supervisor’s effectiveness, and a shift in the way principals exerted instructional leadership. Specifically, supervisors were trained to lead principals toward better practices in observing and assessing classroom instruction, assessing teachers’ professional development needs and implementation of new learning, and providing teacher performance feedback (Goldring et al., 2020).

These findings are important because principals often lack effective skills in evaluating teachers and providing formative feedback (Grissom et al., 2018), and are often unwilling to assign low ratings to teachers in high-stakes evaluation systems (Grissom & Loeb, 2017). Many principals also struggle to differentiate teacher performance on some job dimensions from performance on others, calling into question the value of evaluation scores for feedback and performance improvement (Grissom & Loeb, 2017; Halverson et al., 2004).

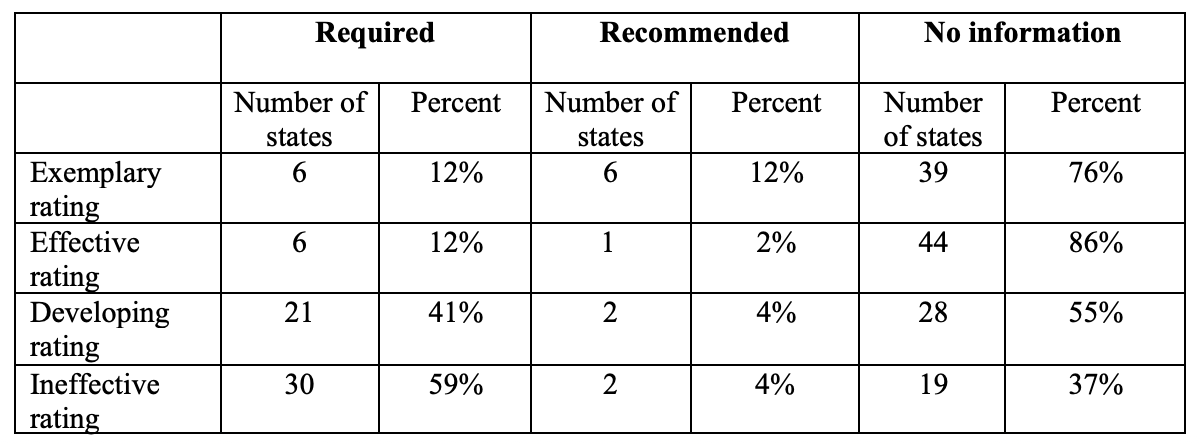

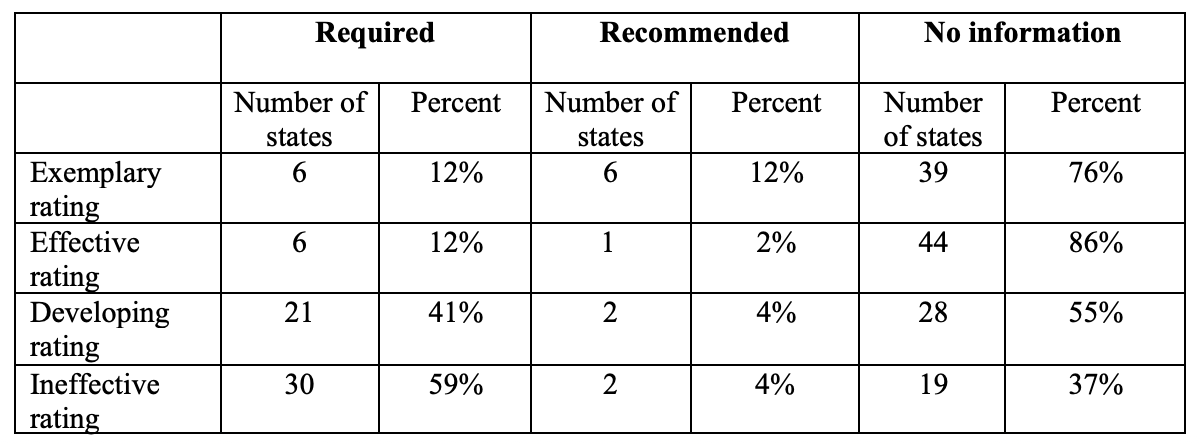

Evaluation Consequences

Table 4 depicts results from recent state policy analysis research by Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021) on the consequences of principal evaluation ratings in place across the country. Most states currently require that districts assign performance ratings to principals based on evaluation results, a clear departure from traditional systems in which evaluations had few negative or positive consequences for school leaders (Reeves, 2005). Ineffective and developing ratings are more likely to result in some type of consequence than effective or exemplary ratings; just 12% of states linked these ratings to positive consequences, such as increased compensation. However, a number of states did not provide information (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al., 2021).

Table 4. Consequences of principal evaluation system ratings across states and Washington, D.C.

Adapted from Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Youngs, et al. (2021), p.351.

Donaldson and colleagues (2021) noted that consequences for inadequate performance are generally consistent across states and typically include a remediation plan, more frequent monitoring through increased observations and evaluations, intensive intervention and support, and termination for those with persistently ineffective ratings. Earlier data from 2019 showed that approximately half of states had begun requiring districts to develop improvement plans to provide support for struggling principals (NCTQ, 2019). Only a handful of states from the NCTQ study required some type of positive consequence for effective ratings, such as fewer observations/longer evaluation cycles, promotions, and additional monetary compensation or leadership roles. These results are generally consistent with those obtained by Fuller and colleagues (2015), who found in their earlier state policy analysis that at least two thirds (66%) of states either allowed, recommended, or mandated results from evaluations be used to make personnel decisions. However, little research has been conducted on the efficacy of using principal evaluation results to make high-stakes personnel decisions (Donaldson, Mavrogordato, Dougherty, et al., 2021; Fuller et al., 2015).

The federal Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF) program was established in 2006 to provide competitive grants to states and districts to enhance educator effectiveness in high-need schools by measuring performance and using the information for decision making about support and compensation; all proposals for funding required incentive plans for principals (Goff et al., 2016). Some evidence about this program comes from research on the Pittsburgh Principal Incentive Program (PPIP), which offered extensive principal leadership development focused on leadership and supervisor feedback/coaching, and provided monetary compensation through permanent salary increases for performance indicative of effective practice, and an annual bonus based primarily on student achievement growth (Hamilton et al., 2012). While participating principals found the program beneficial to their leadership skills, they reported that monetary compensation did not influence their motivation to work harder or change their practices to increase student achievement, and found the idea of “pay for performance” problematic (Hamilton et al., 2012). In addition, they “were much more likely to attribute changes in their leadership behavior to support and feedback than to financial incentives” (Hamilton et al., 2102, p. xv).

Many districts reward exceptional teacher performance using nonmonetary rewards such as improved working conditions, paid leave, and job expansion; as the “overwhelming majority of principals are former teachers, it is likely that principals also view their profession as a form of stewardship, suggesting that non-monetary rewards could be used to motivate their performance as well” (Goff et al., 2016, p. 132). Another study used random assignment to study the pay-for-performance component of TIF, in terms of implementation and impacts of performance bonuses on educator and student outcomes, creating treatment and control group districts (Chiang et al., 2015). Implementation data showed that just 30% of treatment districts awarded principal pay-for-performance bonuses that met grant requirements by being challenging to earn (as demonstrated by less than 50% of principals receiving a pay-for-performance bonus), substantial (as demonstrated by an average bonus that was at least 5% of average annual salary), and differentiated (as demonstrated by a highest bonus that was at least 3 times the average bonus).

The TIF program became the Teacher and School Leaders (TSL) Incentive Program with the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 2015. Two high-quality studies sponsored by the Institute of Education Sciences investigated the impact of evaluations that resulted in performance feedback for educators, and the impact of pay-for-performance bonuses based on performance ratings (Garet et al., 2017; Wayne et al., 2018). The performance feedback study (Garet et al., 2017) included principal evaluations that produced ratings and oral feedback on multiple leadership dimensions (e.g., high standards for student learning) and an overall rating. While formal consequences (e.g., employment or tenure decisions) were not linked to performance ratings, feedback was provided to help identify principals in need of improvement and support. The other study, a follow-up to Chiang et al. (2015), again found that most principals continued to receive the performance bonus, suggesting that these bonuses were not challenging to earn (Wayne et al., 2018).

Communication by districts of the specifics of the pay-for-performance program were often lacking; for example, even at the end of the 4-year program, 20% of principals still were unaware that they were eligible for a performance bonus. Principals in treatment districts, however, were more satisfied than control principals with their opportunities for professional advancement, opportunities to earn extra pay, and recognition of accomplishments (Chiang et al., 2017). Pay-for-performance had no impact on evaluators’ observation ratings of principals. Providing educators with pay-for performance bonuses enhanced student achievement on some but not all measures, and results were mixed regarding educator satisfaction (Chiang et al., 2017). However, any conclusions about how these programs specifically impacted principal performance, retention, and satisfaction were not possible given that the program impact data were combined for teachers and principals.

Goff et al. (2016) reviewed incentive programs described in 34 TIF grants and noted a number of challenges to linking evaluation processes to performance incentives, including a lack of evidence of validity or reliability of measures used in evaluation systems and how these measures were weighted, and failure to connect incentives for professional development programs with district goals. They suggested the following:

When creating an incentive program, schools and districts would benefit from clearly articulating the minimum expectations and then structuring incentives to support leadership outcomes beyond this baseline level. Incentive programs should identify key factors along the path to desired outcomes where districts feel performance is lacking. Additionally, incentive supports should be an explicit part of the incentive system: Outcome incentives may help principals identify what needs to change (e.g., student achievement), but it is the incentive supports that can show principals how to change (e.g., improving classroom observations). (p. 146)

Summary and Conclusions

Principals create school conditions that enable high-quality teaching and learning, and principal evaluation is a critical component of the principal development pipeline. With few exceptions, principal evaluation policies and practices before 2009 across the United States varied considerably and lacked an evidence base, were not reported to be useful for principal improvement, and lacked any connection to student and school outcomes. Federal policy changes and rapidly growing research based on school leadership have led to widespread principal evaluation reform, however. Today’s principal evaluation systems include multiple measures of performance linked to research on effective leadership and student learning outcomes, with the purpose of holding principals accountable as well as supporting and developing them professionally.

Research on the components of current principal evaluation systems show that almost all states require the incorporation of student outcomes and measures of standards-based leadership, which has shifted in focus toward principals as instructional leaders in their buildings. Student outcomes are typically achievement test score data, and often principals are evaluated based on the value-added achievement growth scores of their students. Many researchers have questioned the validity of this practice in terms of the degree to which principals should be held responsible for these outcomes, and the bias that has been observed in evaluations of principals in high-poverty schools, who are typically rated as lower performing based on these data. Some evidence suggests that states are retreating from requiring this type of data, and several studies have documented a shift toward engaging principals instead to use these summative data in continuous improvement and goal setting cycles. Increasingly, stakeholder surveys are also included or recommended in evaluation systems such as VAL-ED, which includes teacher surveys of principal performance.

Principal evaluation processes have also shifted toward more frequent progress monitoring through observation, principal self-assessments, midyear in addition to end-of-year evaluations, and more frequent in-person contact with the principal evaluator, who is often the principal supervisor. Rather than a single summative evaluation at the end of the school year, when it is too late to adjust practice, these ongoing formative evaluation practices may better help principals connect to supports and professional development in a timely manner. In particular, on-the-job mentoring and coaching have proven to be effective principal development practices, as demonstrated through programs such as the Principal Pipeline Initiative and the Texas Principal Evaluation and Support System. However, these and other programs that incorporate newer evaluation systems are not without problems, such as tension that may arise when observation data conflict with student achievement measures, and concerns on the part of the principal that evaluations failed to consider individual school contextual factors influencing results.

These programs generally have resulted in positive principal–supervisor relationships, which are critical in ensuring that principals trust that evaluations are fair and accurate, and that they result in performance improvements. Newer evaluation systems require supervisors to lead principals toward enhancing their capacity as instructional leaders by providing coaching, for example; however, supervisors frequently need additional training as evaluators, and supports in the form of a reduced caseload of principals to supervise. The Principal Supervisor Initiative provided these components, resulting in improved principal perceptions of supervisors’ effectiveness. Supervisors worked with principals to improve their capacity to observe and assess instructional effectiveness and provide constructive feedback to teachers, an important finding given principals’ weaknesses in these skills.

Finally, newer evaluation systems are more likely than traditional systems to incorporate some form of consequence based on evaluation results. Negative results typically lead to increased monitoring, remediation plans that include additional supports, and dismissal if performance continues to be poor. Some states and federal programs have experimented with incentives, in particular pay-for-performance. Results from studies on grantees using monies from the Teacher Incentive Fund to offer educator incentives are mixed, with many implementation challenges (e.g., poor communication of program requirements and bonuses that were too easy to earn), but some successes in principal satisfaction with opportunities for principal advancement. To be effective, these performance systems must not only provide outcome incentives but also link these incentives to supports that demonstrate to principals how to improve their practice.

Citations

Anderson, L. M., & Turnbull, B. J. (2016). Building a stronger principalship: Volume 4: Evaluating and supporting principals. Policy Studies Associates. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED570471.pdf

Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Burkhauser, S., Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., Li, J. J., & Pierson, A. (2013). Laying the foundation for successful school leadership. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR400/RR419/RAND_RR419.pdf

Canole, M., & Young, M. D. (2013). Standards for educational leaders: An analysis. Council of Chief State School Officers.

Chacon-Robles, B. (2018). Improving instructional leadership: A multi-case study of principal perspectives on formal evaluation (Publication No. 1409). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Texas at El Paso]. Open Access Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarworks.utep.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2408&context=open_etd

Chiang, H., Lipscomb, S., & Gill, B. (2016). Is school value added indicative of principal quality? Education Finance and Policy, 11(3), 283–309. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED566133.pdf

Chiang, H., Speroni, C., Herrmann, M., Hallgren, K., Burkander, P., & Wellington, A. (2017). Evaluation of the Teacher Incentive Fund: Final report on implementation and impacts of pay-for-performance across four years (NCEE 2017-4004). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20184004/pdf/20184004.pdf

Chiang, H., Wellington, A., Hallgren, K., Speroni, C., Herrmann, M., Glazerman, S., & Constantine, J. (2015). Evaluation of the Teacher Incentive Fund: Implementation and impacts of pay-for-performance after two years(NCEE 2015-4020). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20154020/pdf/20154020.pdf

Clifford, M., & Ross, S. (2012). Rethinking principal evaluation: A new paradigm informed by research and practice. National Association of Elementary School Principals; National Association of Secondary School Principals. https://www.naesp.org/sites/default/files/PrincipalEvaluationReport.pdf

Coggshall, J. G. (2015). Title II, Part A: Don’t scrap it, don’t dilute it, fix it. Education Policy Center at American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Title%20II%2C%20Part%20A%20-%20Don%27t%20Scrap%20It%20Don%27t%20Dilute%20It%20Fix%20It.pdf

Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) (2015). Model principal supervisor professional standards.https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/2015PrincipalSupervisorStandardsFinal1272015.pdf

Davis, S., Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., & Meyerson, D. (2005). School leadership study: Developing successful principals. Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/school-leadership-study-developing-successful-principals.pdf

Davis, S. H., & Hensley, P. A. (1999). The politics of principal evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 13(4), 383-403.

Davis, S. H., Kearney, K., Sanders, N. M., Thomas, C., & Leon, R. (2011). The policies and practices of principal evaluation: A review of the literature. WestEd. https://www2.wested.org/www-static/online_pubs/resource1104.pdf

DeMatthews, D. E., Scheffer, M., & Kotok, S. (2020). Useful or useless? Principal perceptions of the Texas Principal Evaluation and Support System. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 1–26.

Donaldson, M., Mavrogordato, M., Dougherty, S. M., Al Ghanem, R., & Youngs, P. (2021). Principal evaluation under the elementary and secondary Every Student Succeeds act: A comprehensive policy review. Education Finance and Policy, 16(2), 347–361. https://direct.mit.edu/edfp/article/16/2/347/97157/Principal-Evaluation-under-the-Elementary-and

Donaldson, M., Mavrogordato, M., Youngs, P., & Dougherty, S. (2020). Appraising principal evaluation and development: Current research and future directions. In P. Youngs, J. Kim, & M. Mavrogordato (Eds.), Exploring principal development and teacher outcomes: How principals can strengthen instruction, teacher retention, and student achievement (pp. 56–68). Routledge.

Donaldson, M., Mavrogordato, M., Youngs, P., Dougherty, S., & Al Ghanem, R. (2021). Doing the “real” work: How superintendents’ sensemaking shapes principal evaluation policies and practices in school districts. AERA Open, 7(1), 1–16. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2332858420986177

Fitzpatrick, J. L., Sanders, J. R., & Worthen, B. R. (2011). Program evaluation: Alternative approaches and practical guidelines (4th ed.). Pearson.

Fuller, E. J., & Hollingworth, L. (2014). A bridge too far? Challenges in evaluating principal effectiveness. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(3), 466–499.

Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., & Liu, J. (2015). Evaluating state principal evaluation plans across the United States. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 10(3), 164–192.

Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., & Pendola, A. (2017). The Every Student Succeeds Act, state efforts to improve access to effective educators, and the importance of school leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(5), 727–756. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317199526_The_Every_Student_Succeeds_Act_State_Efforts_to_Improve_Access_to_Effective_Educators_and_the_Importance_of_School_Leadership

Garet, M. S., Wayne, A. J., Brown, S., Rickles, J., Song, M., & Manzeske, D. (2017). The impact of providing performance feedback to teachers and principals (NCEE 2018-4001). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578873.pdf

Ginsberg, R., & Berry, B. (1990). The folklore of principal evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 3(3), 205–230.

Ginsberg, R., & Thompson, T. (1992). Dilemmas and solutions regarding principal evaluation. Peabody Journal of Education, 68(1), 58–74.

Goff, P., Goldring, E., & Canney, M. (2016). The best laid plans: Pay for performance incentive programs for school leaders. Journal of Education Finance, 42(2), 127–152.

Goldring, E. B., Clark, M. A., Rubin, M., Rogers, L. K., Grissom, J. A., Gill, B., Kautz, T., McCullough, M., Neel, M., & Burnett, A. (2020). Changing the principal supervisor role to better support principals: Evidence from the Principal Supervisor Initiative. Wallace Foundation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED607073.pdf

Goldring, E., Cravens, X. C., Murphy, J., Porter, A. C., Elliott, S. N., & Carson, B. (2009). The evaluation of principals: What and how do states and urban districts assess leadership? Elementary School Journal, 110(1), 19–39. https://www.academia.edu/33027832/The_Evaluation_of_Principals_What_and_How_do_States_and_Districts_Assess_Leadership

Goldring, E., Cravens, X., Porter, A., Murphy, J., & Elliott, S. (2015). The convergent and divergent validity of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED). Journal of Educational Administration, 53(2), 177–196.

Goldring, E. B., Mavrogordato, M., & Haynes, K. T. (2015). Multisource principal evaluation data: Principals’ orientations and reactions to teacher feedback regarding their leadership effectiveness. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(4), 572–599.

Grissom, J. A., Blissett, R. S. L., & Mitani, H. (2018). Evaluating school principals: Supervisor ratings of principal practice and principal job performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 446–472.

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. Wallace Foundation. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/How-Principals-Affect-Students-and-Schools.pdf

Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28.

Grissom, J. A., & Loeb, S. (2017). Assessing principals’ assessments: Subjective evaluations of teacher effectiveness in low- and high-stakes environments. Education Finance and Policy, 12(3), 369–395.

Hackmann, D. G. (2016). Considerations of administrative licensure, provider type, and leadership quality: Recommendations for research, policy, and practice. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(1), 43–67.

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010). Leadership for learning: Does collaborative leadership make a difference in school improvement? Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 38(6), 654–678.

Halverson, R., Kelley, C., & Kimball, S. (2004). Implementing teacher evaluation systems: How principals make sense of complex artifacts to shape local instructional practice. In W. K. Hoy & C. Miskel (Eds.), Educational administration, policy, and reform: Research and measurement (pp. 153–188). Information Age.

Hamilton, L. S., Engberg, J., Steiner, E. D., Nelson, C. A., & Yuan, K. (2012). Improving school leadership through support, evaluation, and incentives: The Pittsburgh Principal Incentive Program. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG1223.html

Henry, G. T., & Viano, S. L. (2016). An evaluation of the North Carolina educator evaluation system for school administrators: 2010–11 through 2013–14. Consortium of Educational Research and Evaluation–North Carolina. https://cerenc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Evaluation-of-NC-Principal-Evaluation-FINAL-2-17-16.pdf

Herrmann, M., & Ross, C. (2016). Measuring principals’ effectiveness: Results from New Jersey’s first year of statewide principal evaluation (REL 2016–2156). Regional Educational Laboratory Mid-Atlantic, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/midatlantic/pdf/REL_2016156.pdf

Hitt, D. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 531–569.

Kane, T., & Staiger, D. (2002). The promise and pitfalls of using imprecise school accountability measures. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(4), 91–114.

Kimball, S. M., Arrigoni, J., Clifford, M., Yoder, M., & Milanowski, A. (2015). District leadership for effective principal evaluation and support. Teacher Incentive Fund, U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED566525.pdf

Kimball, S. M., & Milanowski, A. (2009). Examining teacher evaluation validity and leadership decision making within a standards-based evaluation system. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(1), 34–70.

Kimball, S. M., Milanowski, A., & McKinney, S. A. (2009). Assessing the promise of standards-based performance evaluation for principals: Results from a randomized trial. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(3), 233–263.

Lashway, L. (2003). Improving principal evaluation. ERIC Digest. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED482347.pdf

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership and Management, 40(1), 5–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332530133_Seven_strong_claims_about_successful_school_leadership_revisited

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turnaround: How successful school leaders transform low-performing schools. John Wiley & Sons.

Liebowitz, D. D., & Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 785–827.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717.

McCullough, M., Lipscomb, S., Chiang, H., Gill, B., & Cheban, I. (2016). Measuring school leaders’ effectiveness: Final report from a multiyear pilot of Pennsylvania’s Framework for Leadership (REL 2016-106). Regional Educational Laboratory Mid-Atlantic, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED563446.pdf

Mendels, P. (2017). Getting intentional about principal evaluations. Educational Leadership, 74(8), 52–56.

Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., Goldring, E., & Porter, A. (2006). Learning-centered leadership: A conceptual foundation. Wallace Foundation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505798.pdf

National Center on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) (2019). State of the states 2019: Teacher and principal evaluation policy. https://www.nctq.org/pages/State-of-the-States-2019:-Teacher-and-Principal-Evaluation-Policy

National Policy Board for Educational Administration (2015). Professional standards for educational leaders 2015. https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/ProfessionalStandardsforEducationalLeaders2015forNPBEAFINAL.pdf

Porter, A. C., Polikoff, M. S., Goldring, E., Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., & May, H. (2010). Investigating the validity and reliability of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education. Elementary School Journal, 111(2), 282–313.

Portin, B., Feldman, S., & Knapp, M. S. (2006). Purposes, uses, and practices of leadership assessment in education. Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/4-Purposes-Uses-and-Practices.pdf

Reeves, D. B. (2005). Assessing educational leaders: Evaluating performance for improved individual and organizational results. Corwin Press.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on school outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674.

Rogers, L. K., Goldring, E., Rubin, M., & Grissom, J. A. (2019). Principal supervisors and the challenge of principal support and development. In S. J. Zepeda & J. A., Ponticell (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of educational supervision (pp. 433–457). John Wiley & Sons.

Rubin, M., Goldring, E., Neel, M. A., Rogers, L. K., & Grissom, J. A. (2020). Changing principal supervision to develop principals’ instructional leadership capacity. In P. Youngs, J. Kim, & M. Mavrogordato (Eds.), Exploring principal development and teacher outcomes: How principals can strengthen instruction, teacher retention, and student achievement (pp. 41–55). Routledge.

Sanders, K. (2008). The purpose and practices of leadership assessment as perceived by select public middle and elementary school principals in the Midwest (Publication No. 3334686). [Doctoral dissertation, Aurora University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Scott, G. A. (2013). Race to the top: States implementing teacher and principal evaluation systems despite challenges (Report to the Chairman, Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives. GAO-13-777). United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-13-777.pdf

Sun, M., & Youngs, P. (2009). How does district principal evaluation affect learning centered principal leadership? Evidence from Michigan school districts. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(4), 411–445. https://education.uw.edu/sites/default/files/u1406/Sun%20%26%20Youngs%20%282009%29%20district%20evaluation.pdf

Supovitz, J., Sirinides, P., & May, H. (2010). How principals and peers influence teaching and learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 31–56.

Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Supporting principals’ learning: Key features of effective programs. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Supporting_Principals_Learning_REPORT.pdf

Texas Education Agency. (2019). Charting a course for the professional growth and development of principals: Evaluation process. https://tpess.org/principal/evaluation/

U.S. Department of Education. (2009). Race to the Top Program: Executive summary. https://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop/executive-summary.pdf

U.S. Department of Education. (2011). ESEA flexibility: Frequently asked questions. https://www.ed.gov/sites/default/files/esea-flexibility-faqs.doc

Viano, S., Pham, L. D., Henry, G. T., Kho, A., & Zimmer, R. (2021). What teachers want: School factors predicting teachers’ decisions to work in low-performing schools. American Educational Research Journal, 58(1), 201–233.

Wayne, A., Garet, M., Wellington, A., & Chiang, H. (2018). Promoting educator effectiveness: The effects of two key strategies (NCEE 2018-4009). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20184009/pdf/20184009.pdf

Zepeda, S. J., Lanoue, P. D., Price, N. F., & Jimenez, A. M. (2014). Principal evaluation—linking individual and building-level progress: Making the connections and embracing the tensions. School Leadership & Management, 34(4), 324–351. http://www.jess-legs.com/assets/downloads/pdsd/pdsd-scholarship/zepeda-lanoue-price.pdf