Contextual Fit Overview

Introduction

Evidence-based practice is rooted in three key elements: best available evidence, professional judgment, and client values and contextual fit (Spencer et al., 2012). Educational contexts vary widely based on student characteristics, the physical school environment, and personnel training and resources. Horner et al. (2014) defined contextual fit as “the match between the strategies, procedures, or elements of an intervention and the values, needs, skills and resources available in a setting” (p. 1). In other words, a practice may have strong empirical support in the research literature but will inevitably require adaptation when applied in a specific setting. Further, accounting for context can lead to educators implementing interventions with a higher degree of fidelity, which, in turn, can result in improved student outcomes.

Components of Contextual Fit

An intervention with a high degree of contextual fit closely aligns with the values and skills of those implementing it, can be feasibly and sustainably implemented with given resources, and is individualized based on student needs (Albin et al., 1996). Horner et al. (2014) identified eight components of contextual fit:

- Need. Are the outcomes of the intervention important to teachers, administrators, parents and caregivers, and students? This is also a key component of social validity, which asks if the intervention’s goals are important to stakeholders, procedures are acceptable, and outcomes are significant (Wolf, 1978).

- Precision. Are the key elements of the intervention clearly described? They include the following:

- Defining the behaviors or skills of interest and specifying how they will be measured.

- Deciding who will implement the intervention? A teacher, special educator, paraprofessional?

- Deciding where the intervention will be implemented? In the classroom? Cafeteria? Playground? Transitioning between locations?

- Specifying all intervention procedures. How frequently will praise be delivered in the classroom? What exactly will the teacher say? If challenging behavior occurs, how will the teacher respond?

- Evidence base. Has the effectiveness of the intervention been demonstrated? What research has been conducted on the intervention? Is it high quality and relevant to the challenge at hand? (See Best Available Evidence Overview for more details.)

- Efficiency. Consider the time, money, and staff required for the intervention to be effective. If multiple interventions are demonstrated to be effective, stakeholders may choose to implement the most efficient intervention or one requiring fewer resources.

- Skills. What skills do implementors need to successfully apply the intervention? Who will train school personnel on implementing the intervention? Competency-based training—the gold standard for implementation training—involves providing instructions, modeling the intervention procedures, having personnel practice the procedures via role-playing, and providing feedback (Kratochwill et al., 1989).

- Cultural relevance. How does the intervention align with the values of those who are implementing, monitoring, and receiving the intervention? For example, Fetterman et al. (2020) described a case study in which schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports (SWPBIS) were implemented in a Spanish-language magnet school, and identified five aspects of cultural responsiveness, including identity, voicing opinions, supportive environment, situational appropriateness, and data for equity.

- Resources. Are the necessary resources for sustaining the intervention available? Will those implementing the intervention require ongoing training, consultation, or other supports?

- Administrative and organizational support. Do those making administrative decisions support the use of the intervention?

Assessing Contextual Fit

Assessing contextual fit is a critical step in evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention. Detrich (1999) described various strategies for assessing contextual variables.

- Evaluate the characteristics of the student, a process that can involve interviews with teachers and direct observation. For example, create a list of behavioral characteristics, some of which reflect the student of concern, and ask teachers to rate which characteristics are most challenging.

- Directly observe the student and teacher interact with one another and identify the student’s behaviors that the teacher responds to most often.

- Take into account classroom resources. Consider the ratio of staff to students, the classroom schedule, and the allocation of responsibilities.

- Be aware of the financial status of the district.

- Observe the frequency and timing of interactions between teachers and students. Further, observe if instruction occurs in teacher- or student-directed activities, one on one or group settings, and in structured or natural contexts.

- Assess the similarity between the recommended intervention and current classroom practices; this can provide additional insight into the potential effectiveness of the intervention in the current context.

Riley-Tillman and Chafouleas (2003) advised behavioral consultants to make small changes to current classroom practices whenever possible. They cautioned that dramatic changes were more likely to be rejected by those implementing the intervention.

Consider the following example of assessing contextual fit. SWPBIS has been extensively implemented in elementary and middle schools, but less frequently in high schools. Flannery and Kato (2017) described three contextual factors that affect implementation in high school settings: school size, organizational culture, and student developmental level. Larger schools may utilize an administrative team instead of one administrator, with each team member overseeing a different area, such as academics or athletics. This approach requires a greater degree of coordination when implementing a schoolwide intervention. Strong communication is vital to support and sustain implementation. School size also affects students; larger schools may have several feeder districts, leading to more diverse student populations and the reformation of peer relationships when transitioning from middle to high school. When structuring student involvement in SWPBIS, ensure representation across the student population.

Organizational culture consists of the shared values of the organization’s members about the purpose and mechanisms of the organization. Whereas teachers of lower grades teach a wide range of content, including nonacademic areas like social skills, high school teachers focus on specific academic areas and may consider social or behavioral concerns outside their purview. High schools are more likely to have exclusionary disciplinary policies (i.e., suspension, expulsion; Spaulding et al., 2010) as teachers and administrators expect high school students to engage in appropriate academic and social behavior. Successful implementation of SWPBIS requires a consensus on these expectations across school personnel and students, a process that could take several months.

The developmental level of high school students can also affect the contextual fit of SWPBIS. High school students have a greater degree of independence than elementary and middle schoolers, and a greater desire to be involved in decision making. A high schooler may understand expectations but choose to behave outside those expectations, as approval from peers may be more important than approval from adults. Flannery and Kato (2017) suggested including students in decision making as much as possible, through student membership on leadership committees, through student-led initiatives, or by working within existing clubs or organizations.

Effects of Contextual Fit

Contextual fit is important for the sustainable implementation of an intervention, and its effects have been explored in the literature. McIntosh et al. (2014) surveyed 257 educators about the elements of contextual fit they felt were most important for the implementation and sustainability of SWPBIS; these included support from administrators, implementation fidelity, and effective team functioning. Mathews et al. (2014) examined factors that predicted sustained implementation of SWPBIS. Based on a survey of school personnel from 261 schools about the fidelity of implementation of various components of SWPBIS, the researchers found that three practices reliably predicted sustained implementation: (1) regular positive reinforcement and acknowledgement of appropriate behavior; (2) alignment of instruction and materials with student skill levels, including the use of flexible curricula that allow teachers to adapt to varying skill levels in their classrooms; and (3) access to support, including training, coaching, and regular meetings with school teams to refine interventions.

Benazzi et al. (2006) evaluated the effects of three types of behavior support teams (teams without behavior specialists, teams with behavior specialists, and behavior specialists alone) on the technical adequacy and contextual fit of behavior support plans (BSPs) with elementary school students. Team members included general and special educators, administrators, and school psychologists. Behavior specialists included individuals who had completed or nearly completed doctoral study in behavior analysis. The teams were presented with a vignette describing a hypothetical student’s background, problem behavior, and the results of a functional behavior assessment, and were given 75 minutes to develop a BSP.

The BSPs were then rated on a technical adequacy checklist (maximum score of 17) and a contextual fit questionnaire (maximum score of 96). For the BSPs rated on a technical adequacy checklist, plans developed by behavior specialists alone (averaging 13.75/17; 81%) and teams working with behavior specialists (averaging 15/17; 88%) scored significantly higher than plans developed by teams working without behavior specialists (averaging 8.57/17; 50%). For the BSPs rated on a contextual fit questionnaire, plans developed by teams working without behavior specialists (averaging 86.41/96; 90%) and teams working with behavior specialists (averaging 86.68/96; 90%) demonstrated significantly higher contextual fit than behavior specialists working alone (averaging 76.27/96; 79%). That is, the behavior specialists had the highest scores for developing BSPs that aligned with evidence-based practices and were deemed likely to be effective by a panel of experts, while school teams had the highest scores for contextual fit. These results suggest that involving a combination of school personnel and behavior specialists in BSP development can maximize both technical adequacy and contextual fit.

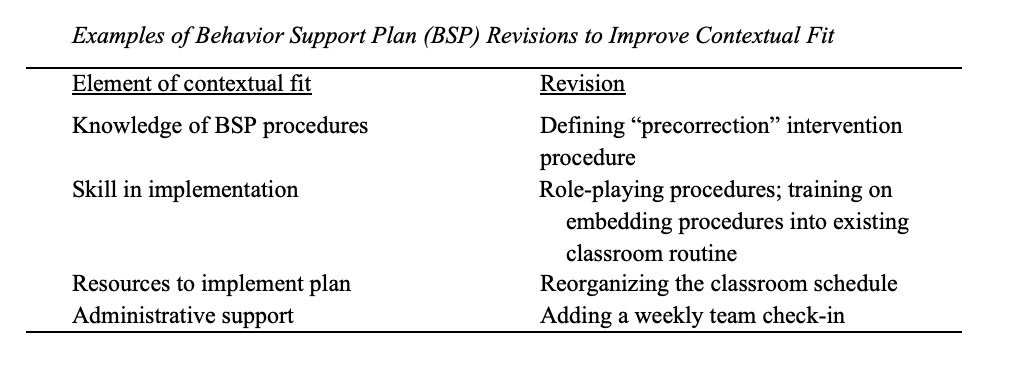

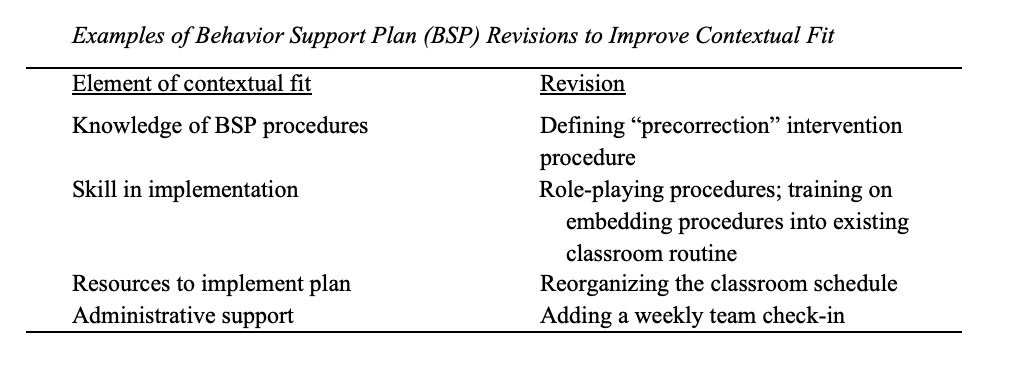

If contextual fit is found to be inadequate, how can it be improved? Monzalve and Horner (2021) evaluated the effects of the Contextual Fit Enhancement Protocol (CFEP) on the fidelity of implementation of BSPs and the level of student problem behavior. The participants were four teacher-student dyads. During baseline, the classroom teachers implemented BSPs as usual without any feedback from the researchers. The CFEP consisted of a 45- to 60-minute meeting between the researchers and the students’ BSP teams, including behavior specialists and classroom teachers. During this meeting, the team reviewed the goals and procedures of the BSP, assessed contextual fit via a checklist (Horner et al., 2003), identified adaptations to improve the contextual fit of the BSP, and planned next steps for implementing the revised BSP.

Table 1 depicts the elements of conceptual fit that received low scores during the meeting and the corresponding revisions.

Table 1

It is important to note that the researchers did not make any changes to the BSP or give the teachers any feedback on their implementation. During baseline, the teachers implemented the BSPs with an average of 15% fidelity and the average level of problem behavior for the students was 46% of observed intervals. After the CFEP meeting, the teachers implemented the BSPs with an average of 83% fidelity and the average level of student problem behavior was 16% of observed intervals.

Conclusions and Implications

Contextual fit involves aligning the procedures of an intervention and the values of those implementing and receiving it, the resources available to support it, and the significance of the outcomes. Assessing the extent of contextual fit is a critical part of the intervention process and can predict the long-term sustainability of the intervention. Many variables contribute to contextual fit, from student characteristics and classroom resources to funding and administrative support. Contextual fit can be improved through collaboration among interdisciplinary team members, including teachers, administrators, consultants, and parents and caregivers. Ultimately, a high degree of contextual fit is necessary to ensure an intervention is implemented with fidelity and produces positive outcomes for students and teachers.

Citations

Albin, R. W., Lucyshyn, J. M., Horner, R. H., & Flannery, K. B. (1996). Contextual fit for behavior support plans: A model for “goodness of fit.” In L. K. Koegel, R. L. Koegel, & G. Dunlap (Eds.), Positive behavior support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community (pp. 81–98). Brookes.

Benazzi, L., Horner, R. H., & Good, R. H. (2006). Effects of behavior support team composition on the technical adequacy and contextual fit of behavior support plans. Journal of Special Education, 40(3), 160–170.

Detrich, R. (1999). Increasing treatment fidelity by matching interventions to contextual variables within the educational setting. School Psychology Review, 28(4), 608–620.

Fetterman, H., Ritter, C., Morrison, J. Q., & Newman, D. S. (2020). Implementation fidelity of culturally responsive school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports in a Spanish-language magnet school: A case study emphasizing context. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 36(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2019.1665607

Flannery, K. B., & Kato, M. M. (2017). Implementation of SWPBIS in high school: Why is it different? Preventing School Failure, 61(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2016.1196644

Horner, R. H., Blitz, C., & Ross, S. W. (2014). The importance of contextual fit when implementing evidence-based interventions [Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Issue brief]. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/importance-contextual-fit-when-implementing-evidence-based-programs

Horner, R. H., Salentine, S., & Albin, R. W. (2003). Self-assessment of contextual fit in schools. University of Oregon. https://specialed.jordandistrict.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/Contextual-Fit-in-Schools.pdf

Kratochwill, T. R., VanSomeren, K. R., & Sheridan, S. M. (1989). Training behavioral consultants: A competency-based model to teach interview skills. Professional School Psychology, 4(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0090570

Mathews, S., McIntosh, K., Frank, J. L., & May, S. L. (2014). Critical features predicting sustained implementation of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 16(3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300713484065

McIntosh, K., Predy, L. K., Upreti, G., Hume, A. E., Turri, M. G., & Mathews, S. (2014). Perceptions of contextual features related to implementation and sustainability of School-Wide Positive Behavior Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 16(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300712470723

Monzalve, M., & Horner, R. H. (2021). The impact of the contextual fit enhancement protocol on behavior support plan fidelity and student behavior. Behavioral Disorders, 46(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742920953497

Riley-Tillman, T. C., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2003). Using interventions that exist in the natural environment to increase treatment integrity and social influence in consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 14(2), 139–156.

Spaulding, S. A., Irvin, L. K., Horner, R. H., May, S. L., Emeldi, M., Tobin, T. J., & Sugai, G. (2010). Schoolwide social-behavioral climate, student problem behavior, and related administrative decisions: Empirical patterns from 1,510 schools nationwide. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12(2), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300708329011

Spencer, T. D., Detrich, R., & Slocum, T. A. (2012). Evidence-based practice: A framework for making effective decisions. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(2), 127–151.

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203

Publications

TITLE

SYNOPSIS

CITATION

LINK

No Child Left Behind, Contingencies, and Utah’s Alternate Assessment.

This paper dissusses the contingencies that create opportunities and obstacles for the use of effective educational practices in a state-wide system.

Hager, K. D., Slocum, T. A., & Detrich, R. (2007). No Child Left Behind, Contingencies, and Utah’s Alternate Assessment. Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools, 8(1), 63–87.

The Evidence-Based Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis

Applied behavior analysis emphasizes being scientifically-based In this paper, we discuss how the core features of evidence-based practice can be integrated into applied behavior analysis.

Slocum, T. A., Detrich, R., Wilczynski, S. M., Spencer, T. D., Lewis, T., & Wolfe, K. (2014). The Evidence-Based Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis. The Behavior Analyst, 37(1), 41-56.

Evidence-based Practice: A Framework for Making Effective Decisions

Synopsis: Evidence-based practice is characterized as a framework for decision-making integrating best available evidence, clinical expertise, and client values and context. This paper reviews how these three dimensions interact to inform decisions.

Spencer, T. D., Detrich, R., & Slocum, T. A. (2012). Evidence-based practice: A framework for making effective decisions. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(2), 127-151.

Identifying research-based practices for response to intervention: Scientifically-based instruction

This paper examines the types of research to consider when evaluating programs, how to know what “evidence’ to use, and continuums of evidence (quantity of the evidence, quality of the evidence, and program development).

Twyman, J. S., & Sota, M. (2008). Identifying research-based practices for response to intervention: Scientifically based instruction. Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools, 9(2), 86-101.

Presentations

TITLE

SYNOPSIS

CITATION

LINK

A Systematic Approach to Data-based Decision Making in Education: Building School Cultures

This paper examines the critical pracitce elements of data-based decision making and strategies for building school cultures to support the process.

Keyworth, R. (2009). A Systematic Approach to Data-based Decision Making in Education: Building School Cultures [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2009-campbell-presentation-randy-keyworth.

Building a Data-based Decision Making Culture through Performance Management

This paper examines the issues, challenges, and opportunities of creating a school culture that uses data systematically in all of its decision making.

Keyworth, R. (2009). Building a Data-based Decision Making Culture through Performance Management [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2008-aba-presentation-randy-keyworth.

A Systematic Approach to Data-based Decision Making in Education

Systematic data-based decision making is critical to insure that educators are able to identify, implement, and trouble shoot evidence-based interventions customized to individual students and needs.

Keyworth, R. (2010). A Systematic Approach to Data-based Decision Making in Education [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2010-hice-presentation-randy-keyworth.

Contingencies for the Use of Effective Educational Practices: Developing Utah’s Alternate Assessment

This paper dissusses the contingencies that create opportunities and obstacles for the use of effective educational practices in a state-wide system.

Slocum, T. (2006). Contingencies for the Use of Effective Educational Practices: Developing Utah’s Alternate Assessment [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2006-wing-presentation-tim-slocum.

Identifying Research-based Practices for RtI: Scientifically Based Reading

This paper examines the types of research to consider when evaluating programs, how to know what “evidence’ to use, and continuums of evidence (quantity of the evidence, quality of the evidence, and program development).

Twyman, J. (2007). Identifying Research-based Practices for RtI: Scientifically Based Reading [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2007-wing-presentation-janet-twyman.

Research Based Dissemination: Or Confessions of a Poor Disseminator"

This paper shares research on what makes ideas "stick" (gain acceptance, maintain) within a culture and provided an acronym from the results: SUCCESS (simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional, involve stories).

Cook, B. (2014). Research Based Dissemination: Or Confessions of a Poor Disseminator" [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2014-wing-presentation-bryan-cook.

If We Want More Evidence-based Practice, We Need More Practice-based Evidence

This paper discusses the importance, strengths, and weaknesses of using practice-based evidence in conjunction with evidence-based practice.

Cook, B. (2015). If We Want More Evidence-based Practice, We Need More Practice-based Evidence [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2015-wing-presentation-bryan-cook.

The Four Assumptions of the Apocalypse

This paper examines the four basic assumptions for effective data-based decision making in education and offers strategies for addressing problem areas.

Detrich, R. (2009). The Four Assumptions of the Apocalypse [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2009-wing-presentation-ronnie-detrich.

Evidence-based Practice for Applied Behavior Analysts: Necessary or Redundant

Evidence-based practice has been described as a decision making framework. This presentation describes the features and challenges of this perspecive.

Detrich, R. (2015). Evidence-based Practice for Applied Behavior Analysts: Necessary or Redundant [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2013-aba-presentation-ronnie-detrich-tim-slocum-teri-lewis-trina.

Workshop: Evidence-based Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis.

Evidence-based practice is a decision-making framework that integrates best available evidence, professional judgement, and client values and context. This workshop described the relationship across these three dimensions of decision-making.

Detrich, R. (2015). Workshop: Evidence-based Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis. [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from 2015-missouriaba-workshop-presentation-ronnie-detrich.