Principal Professional Development Overview

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2021). Principal Preparation. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-leadership-in-service.

Principal Professional Development PDF

Effective principals—key for high-quality teaching and learning in schools—exert a strong but indirect influence on student learning and achievement as well as school improvement efforts (Hallinger & Heck, 2010; Hitt & Tucker, 2016; Leithwood et al., 2010, 2020; Robinson et al., 2008; Supovitz et al., 2010). In fact, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires that every school be staffed with an effective leader (Fuller et al., 2017). Ensuring effective school leadership requires best practice in each phase of the principal development pipeline, from recruiting the right candidates to providing ongoing support throughout their careers.

Research suggests that principals tend to become more effective after 3 years as they gain experience on the job (Béteille et al., 2011); however, significant numbers of principals leave schools each year, many within the first 3 years of tenure (Goldring & Taie, 2018; School Leaders Network, 2014). Principal attrition is costly (School Leadership Network, 2014), and investments in improved principal retention are an effective way to improve teaching and learning (Wallace Foundation, 2011). The role of principal has become increasingly complex, stressful, and time demanding due to heightened accountability pressures and the highly influential part a principal plays in student learning outcomes (Davis et al., 2005; Fusarelli & Militello, 2012). In fact, many new principals report feeling overwhelmed and anxious during their first year (Lashway, 2003). Research suggests that, optimally, principals should be in place at a school for 5 to 7 years for the school to benefit from their leadership (Wallace Foundation, 2013), making early-career retention paramount.

Principals also need ongoing, high-quality in-service training and support, such as mentoring and coaching programs, which are critical in developing and keeping effective principals (Coggshall, 2015; Sutcher et al., 2017). However, a review found that as of the 2015–2016 school year, only 20 states required some type of support for new principals, and just six required any support beyond a principal’s first year (Goldrick, 2016). School districts, as well, often overlook professional development for principals, focusing resources and support primarily on teachers (Manna, 2015; Rowland, 2017; School Leaders Network, 2014).

Principal professional development encompasses multiple phases including recruitment and selection, completion of a preparation program, initial licensure, induction, and continuing professional development (Gordon, 2020; Steinberg & Yang, 2020). This report provides an overview of research addressing the phases of principal development following completion of the preparation program (see Principal Preparation Overview for information on pre-service training).

Principal Licensing and Certification Systems

Candidates intending to become school principals progress through several stages of professional development. The administrative credential, or license, which signals entry-level educator competence in leadership, is required in all 50 states (Scott, 2017). State licensing systems require the following (Gordon & Niemiec, 2020): (1) teaching experience, required by 37 states; (2) completion of an approved university-based or alternative preparation program (see Principal Preparation Overview), required by all 50 states; (3) field experience, required by 38 states; (4) a master’s degree in educational leadership or a related field, required by 37 states; and (5) passing of a state licensure assessment of knowledge and skills needed to be a principal, required by 33 states.

Hackman (2016) notes that, in some cases, states grant licensure based solely on successfully passing an administrator exam and, in fewer cases, allow those lacking a license to work as principals. Graduates earning licenses typically then apply for and move into administrative positions to become assistant principals and eventually principals; however, many complete advanced degrees and licensure for other reasons (e.g., to earn higher salaries) without intending to pursue administrative roles (DeAngelis & O’Connor, 2012). Initial licensure represents entry-level skills and knowledge, and most states now utilize a two-tiered system that includes requirements and evaluation for advanced licensure, such as completion of an induction program and continuing professional development (Roach et al., 2011; Vogel & Weiler, 2014).

States typically mandate license renewal every 5 years based on semester hour credits or continuing education units (CEUs) related to professional development centered on school improvement and student achievement (Roach et al., 2011). Effective principal licensure systems can “help steer principals toward professional development that is tied to important skill sets or knowledge…[and]…serve broader strategic goals rather than simply creating new sets of boxes for principals to check off as ‘done’” (Manna, 2014, p. 37). However, little is known about the impact of different licensure systems on principal effectiveness (Grissom et al. 2019).

Role of Advanced Degrees in Licensure and Professional Development

The research evidence on the influence of advanced degrees on principal effectiveness is mixed (Grissom et al., 2021). Several studies conducted in the 1990s that examined the importance of principals holding advanced degrees (master’s or doctoral) in educational administration found no evidence that these degrees were related to any measures of school effectiveness (Haller et al., 1997), and, in fact, the degrees were associated with negative performance ratings by teachers (Ballou & Podgursky, 1995). However, most states continue to require advanced degrees for principal licensure, as described by Cheney and Davis (2011), who discussed the weaknesses of state licensure systems:

In setting these requirements states are assuming that a master’s degree is needed to do the job effectively. Yet there is little indication that time in a university classroom is necessary or sufficient for preparing principals for the myriad responsibilities and challenges they face when leading schools. We have no evidence that a master’s degree correlates with principal effectiveness, and yet the master’s degree requirement grants monopoly power to universities, limiting the expansion of a more diverse set of providers, including nonprofits and school districts. (p. 18)

Grissom and Harrington (2010) also found that principals who invested in university coursework as a professional development strategy were rated as less effective by teachers, and schools led by these principals passed fewer state and district standards. Young et al. (2008) found that a principal’s educational level did not predict student achievement; however, another study, by Valentine and Prater (2011), found that increasing levels of principal education were significantly related to positive student achievement outcomes. In a study of predictors of student achievement, Bastian and Henry (2015) determined that different kinds of master’s degrees produced similar achievement growth, but some types of doctoral degrees, particularly those earned at private institutions, were associated with less growth.

Importance of Standards

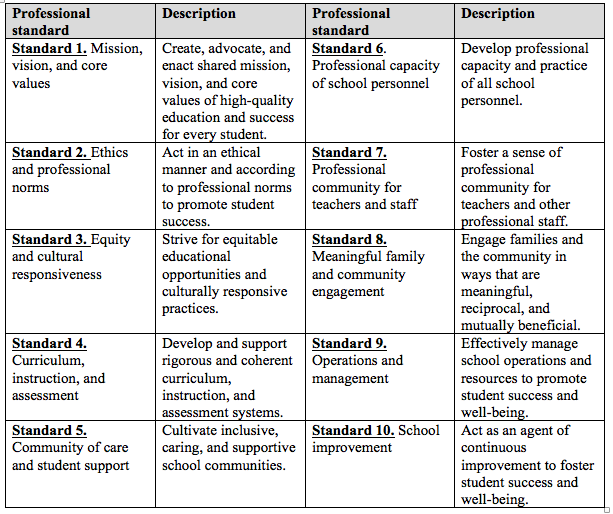

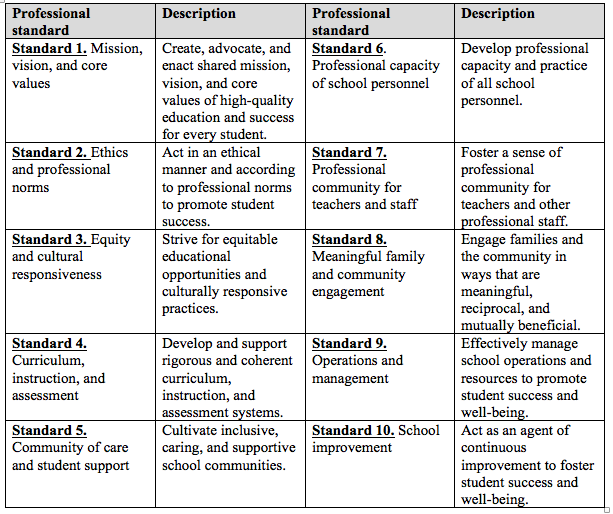

All 50 states have developed or adopted school leadership standards as part of their licensure systems (Educational Testing Service [ETS], 2021). In 1996, the Interstate School Leadership Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) developed national educational leadership standards that were widely adopted by schools across the country (Goldring et al., 2009). Research subsequently demonstrated that use of these standards was found in high-quality, effective principal preparation programs (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007). These standards were revised and updated in 2015 as the Professional Standards for Education Leaders (PSEL) to “guide professional practice and how practitioners are prepared, hired, developed, supervised and evaluated” (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2015, p. 2). Educational leadership standards, which are critical for fostering principal development, have evolved over time to emphasize principals as instructional leaders in their buildings (Canole & Young, 2013; Hackman, 2016). Still, there is little evidence that standards are incorporated into licensing requirements consistently across states (Adams & Copland, 2005; Vogel & Weiler, 2014). The PSEL standards are shown in the table below.

Table 1

Professional standards for educational leaders

Adapted from National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2015, p. 27.

Standards are important for professional development more generally. Principal professional development is often highly variable and determined by where principals work (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007); this inconsistency is due, in part, to a lack of common standards (Darling-Hammond et al., 2010). Rowland (2017) recommended that states adopt PSEL to guide their work with districts as they structure principals’ professional development. Districts, in turn, can engage local stakeholders as they align their current standards with PSEL to ensure that professional development is based on the latest research on best practice (Rowland, 2017). Scott (2018) noted that 10 states had adopted PSEL standards, with the remaining states instituting their own standards (many of which closely resemble PSEL).

Licensure Assessment

As noted previously, most states include satisfactory completion of initial licensure exams as part of their credentialing system to determine whether candidates have the competencies necessary to perform tasks that enable school success (Anderson & Reynolds, 2015). All but 15 states and the District of Columbia currently incorporate a licensure exam in their systems; the remaining 35 states use either a state-designed exam or an exam designed for broad use nationally by companies such as ETS or Pearson (Gordon & Niemiec, 2020). The most commonly used national exam is the School Leaders Licensure Assessment (SLLA), a 4-hour computer-based standardized test consisting of multiple-choice and constructed response (apply knowledge/skills to real-world situations or tasks) questions designed to assess candidates’ knowledge and skills related to professional educational leadership standards (Anderson & Reynolds, 2015; Grissom et al., 2017). In 2018, SLLA was revised to align with PSEL standards and is currently in use in 14 states and the District of Columbia (Gordon & Niemiec, 2020). Some states also contract with companies to design tests to meet the state’s desired instrument format, content, and process, such as the Massachusetts Performance Assessment for Leaders (PAL) developed by Pearson (Gordon & Niemiec, 2020; Orr et al., 2018). These tests may be written exams or, in some cases, performance based (Orr et al., 2018).

Licensing exams have come under some criticism by researchers due to a lack of positive impact on principal retention (Fuller & Young, 2009) and a lack of relationship with job performance (Grissom et al., 2017). In an analysis of SLLA data in Tennessee, Grissom and colleagues found that non-White candidates scored significantly lower than White candidates and were less likely to achieve the required state licensing score; however, SLLA was not predictive of principal job performance as defined by principal supervisor ratings, student achievement data, and teacher survey data (Grissom et al., 2017). Principals with higher scores were more likely to be hired as principals, and the researchers suggested that “failure to obtain the required cut score may be an important barrier to increasing racial and ethnic diversity in a principal workforce that is overwhelmingly White” (Grissom et al., 2017, p. 273). Indeed, 80% of principals are White (Taie & Goldring, 2019), and research has documented inequitable pathways to the principalship by race and gender; for example, Black assistant principals are less likely to be promoted than their White counterparts (Bailes & Guthery, 2020; Davis et al., 2017; Fuller et al., 2019).

A recent research project had an expert panel of educational leadership professionals recommend elements of transformative (i.e., cutting-edge) principal licensure systems with the potential to maximize principal effectiveness (Gordon & Niemiec, 2020). In addition to the traditional requirements often included in licensure systems (e.g., teaching experience, master’s degree, field experience embedded in coursework, internship, criminal background check, preparation program endorsement, and issuing of a renewable certificate), the panel recommended the use of an assessment exam based on national standards such as PSEL and capable of measuring “higher-level capacities that integrate knowledge, skills, and dispositions” (Gordon & Niemiec, 2020, p. 110). The panel discouraged written exams that included primarily multiple-choice questions and instead recommended the use of constructed responses to scenarios, videos, and short case studies.

The panel and others with expertise advocated that transformative licensure assessment systems include ways of measuring candidates’ competencies in multiple assessment contexts (e.g., online, university or PK–12 school campus, statewide assessment system), supplementing exams with methods such as performance-based assessment and portfolios that include items such as videos, reports, interviews, and journals, to fully capture a candidate’s capacity to perform school leadership work effectively (Anderson & Reynolds, 2015; Gordon, 2020; Gordon & Niemiec, 2020). It was also important for states to ensure that licensure assessment systems, particularly those including high-stakes exams, were bias-free and equitable for all cultural groups. Gordon (2020) noted that this was an understudied but critical issue, and that “equity research will need to be carried out not only on the development and use of assessment instruments but also, following licensure assessment, in school districts (e.g., research on hiring decisions, principal performance, and principal retention in relationship to licensure assessment results)” (p. 71).

Once principals attain licensure and a principalship, professional development continues in the form of in-service learning through induction processes at the outset of tenure, and continued professional learning to maintain initial licensure (Steinberg & Yang, 2020). This continued learning is important, as research suggests that principals receiving in-service professional development are more likely to remain at their schools than those not receiving it (Goldring & Taie, 2014; Jacob et al., 2015; Steinberg & Yang, 2020).

Principal Induction

The first few years of principalship determine whether principals acquire the competencies and confidence necessary to perform their roles or leave their positions (Shoho & Barnett, 2010). Given that the average tenure of a school principal at a given school is 4 years (Taie & Goldring, 2017), many new principals may not receive adequate support to enhance their competencies and confidence in their roles, and instead are expected to “hit the ground running” (Shoho & Barnett, 2010). Principal induction is “a multidimensional process that orients new principals to a school and school system while strengthening their knowledge, skills, and dispositions to be an educational leader” (Villani, 2006, p. 19).

Little in the way of systematic evidence is available regarding the efficacy of in-service induction programs, (Manna, 2015; Rowland, 2017). One exception is the New Leaders’ Aspiring Principals Program, an alternative certification program that recruits and trains aspiring principals who then serve in urban high-need schools. The program provides the core elements of selective recruitment and admission, residency-based training, and early tenure endorsement and support (Gates et al., 2014). It also heavily invests in induction processes during residency, such as job-embedded coaching and building peer support networks. Researchers found that students in schools led by program graduates were more likely to attend school and made significantly larger achievement gains in reading and math than students at schools led by non-program principals, and that program principals were more likely to be retained (Burkhauser et al., 2012; Gates et al., 2014, 2019). Steinberg and Yang (2020) demonstrated that Pennsylvania’s Inspired Leadership Induction Program increased principal tenure by 18%, although the program had no impact on teacher effectiveness or student achievement.

Recommended practices for induction programs, drawn from related research and experts in the area, can also be found in the literature. For example, listening to and considering multiple perspectives help adults recognize and solidify their own values and beliefs, and deepen their inquiry and discovery (Drago-Severson, 2008). Principal induction programs should include socialization opportunities, offering new principals an opportunity to share challenges and insights as they learn from and with peers (Fusarelli et al., 2018). New principals benefit from collaborative learning structures, such as professional learning communities (PLCs) or cohorts, to help them be less isolated in their roles (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Sutcher et al., 2017). Prior to the first year of principalship, high-quality summer induction programs can help principals prepare to welcome staff and students, as described by NYC Leadership Academy (n.d.):

We believe this should include a learning experience through which principals can apply role-playing, analysis and decision-making in an authentic way. Simulations are a powerful tool to help aspiring principals develop key skills and engage in hands-on work that mirrors real-life experience. Summer induction should also include a combination of “just-in-time” technical information (key policies, systems, timelines, etc.), introductions to the district-level people they can go to for help with various issues (HR, finance, etc.), and the development of a vision and entry plan for their new role.

Induction programs typically include ongoing professional development sessions throughout the first year to engage new principals with desired district content (e.g., school improvement planning), provide further opportunities for collegiality and networking, and pair new principals with mentors and coaches to provide support (Shoho & Barnett, 2010).

Principal Coaching and Mentoring

Coaching and mentoring, which are frequently included in principal induction programs, offer non-evaluative and confidential support, and can help school leaders better understand their work and help them succeed in their roles (Lochmiller, 2014). Indeed, coaching and mentoring are considered to be key features of effective principal professional development (Turnbull et al., 2013). The two terms are often used interchangeably, but coaching generally occurs over a specific period of time, targeting a specific set of skills (Grissom & Harrington, 2010); mentoring, on the other hand, typically describes guidance and support specifically for new principals (Rowland, 2017). Coaching and mentoring are consistent with all aspects of supporting adult learning (Knowles et al., 2005), and are essential to facilitate transfer of new learning to the school setting and ultimately to sustain changes to practice (Desimone & Pak, 2017; Kraft et al., 2018; Southern Regional Education Board, 2007; Zepeda, 2013).

A mentor for a novice principal is often an “experienced principal from another in-district school, a central office administrator with experience as a principal, or a retired principal” (Gordon, 2020, p. 75). Effective mentors for new principals share their expertise and help new educators reflect on their practice (Mendels, 2016), as well as “help candidates link their experiences to the theories and problem-based activities they learn in their coursework” (Sutcher et al., 2017, p. 10). Mentoring programs provide opportunities for sharing information and practices between novice principals and those with more experience, thus enhancing leadership capacity in a district through job-embedded professional development (Browne-Ferrigno & Muth, 2004). Mentors themselves often experience significant benefits in mentoring novice principals, such as increased career development opportunities, job and personal satisfaction, capacity for self-reflection, and networking opportunities (Dukess, 2001; Ehrich et al., 2004; Hansford & Ehrich, 2006).

Many studies provide research support for the use of coaching and/or mentoring strategies for fostering principal development. One randomized study of leadership coaching of urban principals in a large district found that coaching significantly enhanced principals’ capacity to communicate with teachers about instructional practice and enabled their ability to enact instructional leadership behaviors (Bickman et al., 2012). Grissom and Harrington (2010) found that teachers rated principals participating in formal mentoring or coaching programs as much more effective than those taking university courses for professional development. Recent data found that fewer principals reported taking university courses as a mode of professional development (Lavigne et al., 2016; Lewis & Scott, 2020; Taie & Goldring, 2019). Other coaching models, while lacking empirical research support, include components demonstrated to be effective in a logic model (Herman et al., 2017). For example, Lee (2010) found that district coaching that included principal-coach participation in professional development as well as individual leadership coaching helped both novice and experienced principals become more learner centered.

Goldring et al. (2009) found that shifting the focus of the principal supervisor’s role from compliance to instructional leadership and principal support (through one-on-one coaching and peer observations) resulted in more positive and productive principal-supervisor relationships. School districts, in fact, are exploring such a shift from compliance to ongoing job-embedded professional support (Drucker et al., 2019; Rainey & Honig, 2015). However, several studies suggest that trusting relationships and the sharing of confidential information between principals and coaches are made easier when coaches are from outside the principal’s district (Bloom et al., 2005; Wise & Jacobo, 2010). These findings suggest the need for caution in having principal supervisors provide direct coaching to the principals they supervise (Klar & Huggins, 2020).

Coaching and mentoring are most effective when certain features and program components are in place. Ensuring a good match between mentor and mentee is important, and districts often attempt to make matches based on characteristics such as demographics, geography, or other similar personal characteristics (Alsbury & Hackmann, 2006). New principals benefit in terms of leadership development and capacity to enact shared leadership and innovation when they have a similar educational philosophy and experience as their mentors; poor matches resulted in discussion topics that were restricted to school management rather than broader topics such as curriculum innovation and shared leadership (Oplatka & Lapidot, 2018). New principals need to build their capacity to self-reflect, and they can facilitate that reflection through active listening, asking insightful questions, presenting alternative views, and sharing feedback (Hall, 2008).

The Wallace Foundation (2007, 2008) identified five components of effective coaching/mentoring programs: (1) formal selection criteria for mentors, (2) formal training of mentors, (3) purposeful and strategic assignment of mentees, (4) mentor compensation through financial means or professional growth opportunities, and (5) program design that develops the growth of both mentor and mentee. Simon et al. (2019) added that mentoring should not focus solely on the principal’s technical needs, but should also attend to his or her health and well-being, and that the mentor should facilitate a new principal’s professional networking with other school leaders, including new principals. Mentors should also be aware that their mentees are working in a unique context, and take care not to assume that strategies and techniques that have worked in the past can be used as prescriptions for new principals (Gordon, 2020). Instead, “assistance to the new principal should take the form of co-inquiry to frame and solve problems being experienced by the novice” (Gordon, 2020, p. 76).

While state education leaders increasingly prioritize coaching and mentoring as key components of principal professional development, a review of ESSA shows that these initiatives are devoted primarily to novice principals and those in need of substantial improvement (Riley & Meredith, 2017). Daresh (2007) found that principals were able to shift from a focus on managerial competence to instructional leadership only after at least 2 to 3 years of mentoring support. Evidence suggests that even experienced principals need continuous, job-embedded professional development support such as coaching as they face various challenges throughout their career (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Sutcher et al., 2017).

In-Service Principal Professional Development

Principals need high-quality professional learning opportunities to build their leadership capacity, including ongoing training to update their skills and knowledge, individualized support through mentoring and coaching, and peer networks that encourage colleagues to share and brainstorm problems of practice (Jacob et al., 2015; Tekleselassie & Villareal, 2011). This report provides descriptive information regarding the status of principal professional development in the United States, followed by a discussion of evidence-based practices.

Need for High-Quality Effective Professional Development

Professional learning for school leaders, while often more intensively focused earlier in the career, continues to some extent throughout a principal’s career and may involve continued professional development, conference attendance, and coaching or mentoring (Herman et al., 2017). Recent data suggest that fewer than one-third of districts report using Title II funds—provided by the federal government in the form of subgrants to local education agencies (LEAs) to improve the quality of teachers and administrators—for principal professional development (U.S. Department of Education, 2015), and even when principals receive this training it is often designed for teachers rather than school leaders (Rowland, 2017). Professional development for principals often uses the “sit and get” workshop format (Ikemoto et al., 2014), and is frequently centered on the what of district reform rather than the how of leading school improvement (School Leaders Network, 2014). For example, Clifford and Mason (2013) found that while many principals attended training sessions on standards, curriculum, and assessment for the Common Core, they reported that the sessions did not address leadership tasks and failed to provide guidance on specifically how to make changes to incorporate the standards in their buildings.

Sutcher et al. (2017) conducted a review of the literature on the elements of high-quality principal development related to improved school outcomes such as increased principal and teacher retention and student learning; they concluded that program content should include topics such as leadership to manage change, ways to create collegial environments, whole child education, and increasing equitable outcomes for students. Effective principal development further includes “authentic, job-embedded professional learning opportunities, including applied learning experiences, individualized support from mentors or coaches, and networking structures such as professional learning communities (PLCs)” (Levin et al., 2020, p. 2).

A national survey of elementary school principals revealed that a substantial majority (at least 80%) reported access to professional learning that included research-based content; however, far fewer reported participating in authentic, job-embedded professional learning such as regularly shared leadership practices with peers (32%), working with a mentor or coach (23%), and regular participation in a PLC (56%). Further analysis showed that just 10% of principals in high-poverty elementary schools reported having a mentor or coach within the past 2 years. Additionally, more than four in five (84%) reported barriers to pursuing professional development, such as insufficient coverage for leaving the building, and lacking money for training. The above findings by Levin et al. (2020) are troublesome, particularly as research shows that principals need continuous training and development that is personalized to their context, combined with time to reflect on and refine practice (Coggshall, 2015).

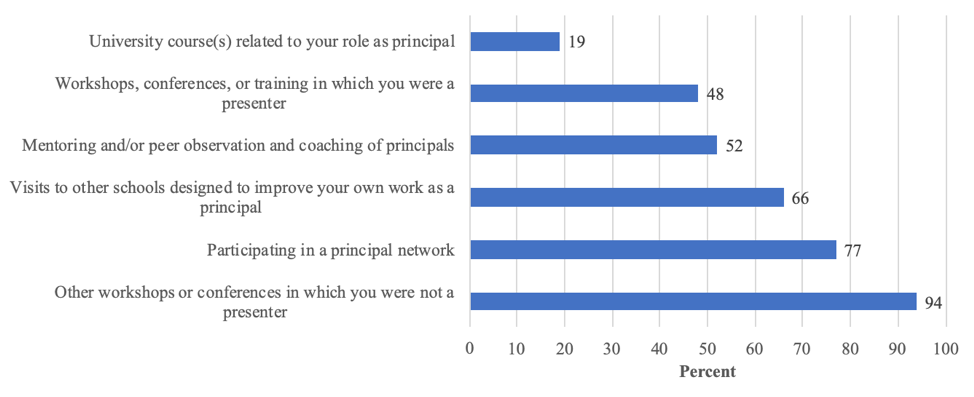

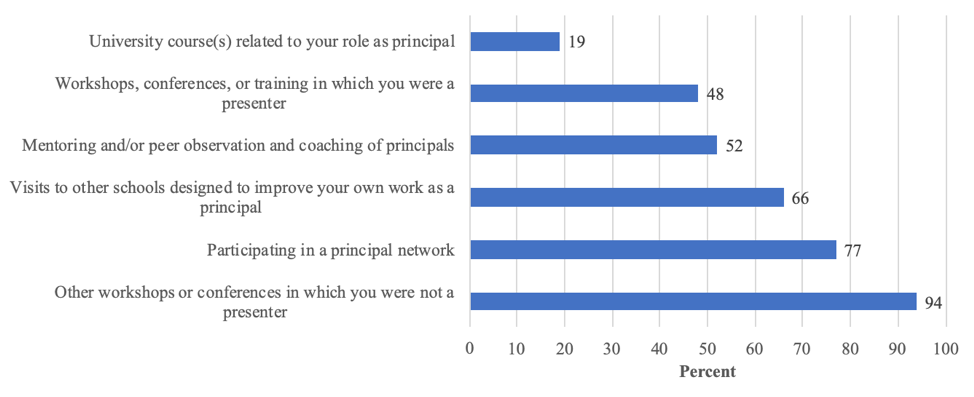

Recent data from the National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS) describe the broad types of professional development reported by principals at all levels with at least 1 year of experience. While almost all principals reported attending workshops or conferences, only slightly more than half reported participating in coaching, mentoring, or peer observation (Lewis & Scott, 2020).

Figure 1

Percentage of principals participating in various kinds of professional development in 2017–2018, results from the National Teacher and Principal Survey

Adapted from Lewis and Scott, 2020

Adapted from Lewis and Scott, 2020

These NTPS data, which covered a larger sample of principals, are generally consistent with the findings reported above by Levin and colleagues (2020). Just over half of principals reported participating in mentoring or coaching, although this is a research-supported professional development strategy. Two-thirds visited other schools to improve their work, but few reported taking university courses related to their role. In-service university coursework as professional development has been shown through research to have a negative impact on teachers’ perceptions of principal effectiveness and actual school outcomes (Grissom & Harrington, 2010). These two studies together suggest the need for extending authentic and job-embedded experiences as part of professional development programs more frequently and to greater numbers of principals throughout the country.

Research Base for Effective In-Service Professional Development

Despite the substantial evidence base for principal mentoring and coaching, only about half of principals have access to such job-embedded professional learning, making this an area for improvement (Grissom & Harrington, 2010; Turnbull et al, 2013). Slightly more than three-quarters of principals in the NTPS data reported being involved in a principal network, a widely advocated professional development strategy (Sutcher et al., 2017). Networks meet regularly and address common problems of practice, allowing principals to share best practices and to problem solve (Sutcher et al., 2017). One practice related to networks involves the use of instructional rounds, in which “school leaders identify a problem of practice specific to student learning and then work with a network of administrators and educators across the district to determine the root causes of the problem through observation, analysis, and dialogue” (Rowland, 2017, p. 6). Together they collaborate to identify strategies and next steps to address the problem, meeting regularly to help principals hone their thinking and practice (City et al., 2009).

Similar to networks, PLCs are used as a form of principal professional development. They involve “district and school leaders work[ing] together to set common goals, learn new skills, and coach one another” (Psencik & Brown, 2018, p. 50). Psencik and Brown found that PLCs enhanced school leadership skills, fostered coherent leadership across the district, and created trusting relationships that enabled collaborative problem solving. Networks and PLCs are examples of adult learning strategies that support the desires of many educational leaders to learn from each other, and working on common problems in the company of other educational leaders is a strategy that is almost universally motivating for participants (Yoon et al., 2007; Zepeda, 2013).

While there is evidence that coaching and networking are effective principal development strategies, high-quality, rigorous research designs examining professional development programs that incorporate these and other strategies are largely missing from the literature (Rowland, 2017). Several exceptions that meet ESSA requirements for high-quality research are described below.

Large-Scale Professional Development Initiatives

McREL Balanced Leadership Program. This program is designed to provide research-based guidance in the form of 21 key leadership responsibilities that help principals become more effective and improve their capacity to enhance student achievement (Jacob et al., 2015). These 21 leadership responsibilities were originally derived from a meta-analysis of leadership studies conducted over a 30-year period (Waters et al., 2003) and have been confirmed through subsequent research (Miller et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2008). The professional learning and coaching program not only includes an explanation of what and how to accomplish these leadership actions, but also devotes time to helping principals understand why they are essential and when to fulfill them for maximum positive impact (McREL International, 2021).

The cohort-based program includes ten 2-day workshops over a 2-year period, with principals applying learned strategies between sessions and reflecting on these applications with trainers and other principals in their cohort (Miller et al., 2016). While internal evaluations have consistently demonstrated effectiveness, a recent randomized control trial study of rural schools in Michigan showed that the program reduced principal and teacher turnover and improved principal efficacy, but failed to impact student achievement or teacher reports of instructional climate (Jacob, et al., 2015).

A subsequent randomized control study also demonstrated significantly greater self-reported growth in principal efficacy for instructional leadership, school norms for teacher collaboration and differentiated instruction, and reported capacity to manage change for balanced leadership as opposed to matched comparison group principals (Miller et al., 2016). However, balanced leadership principals did not report “growth in practices that involved them directly in teachers’ work around curriculum, instruction, and assessment” (Miller et al., 2016, p. 559). The researchers noted that professional development programs that involved principals working more directly with teachers had the capacity to demonstrate more direct results with teaching and learning.

National Institute for School Leadership Executive Development Program. The National Institute for School Leadership (NISL) provides professional development to aspiring and current school leaders to equip them in effectively setting direction and supporting teachers, and in designing a high-performing system rooted in professional learning (Nunnery et al., 2010). The program emphasizes principals’ strategic thinking: how they can effectively coach teachers, and how they can drive and sustain school transformation. The program structure includes in-person and virtual coursework, and emphasizes interactive learning through “simulations, case studies, school evaluations, and online activities” (Nunnery et al., 2010, p. 6).

Several high-quality studies yielded significant positive achievement results in K–12 schools in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania (Nunnery et al., 2010, 2011). They also demonstrated that the program was well implemented and a more cost-effective option than other forms of professional development. Subsequent case study and survey research has shown that principals believed the program enhanced their ability to conceptualize and lead school improvement. They also reported highly valuing NISL coaches with whom the principals brainstormed and problem solved, and that they would highly recommend the program to colleagues (Wang et al., 2019).

Center for Educational Leadership at the University of Washington. Hermann et al (2019) examined the impact of a wide-scale principal professional development program focused on instructional leadership, in particular, principal capacity to conduct structured observations of classroom instruction and provide teachers with targeted feedback. The program, offered by the Center for Educational Leadership at the University of Washington, provided 188 hours of professional development for principals of 100 lower performing elementary schools. It included an in-person summer institute and in-person trainings, quarterly virtual professional learning community meetings, and individualized coaching across a 2-year period; approximately half of the hours were dedicated to individualized coaching. Results showed little change to principal practice, and the program failed to impact either teacher retention or student achievement.

Summary and Conclusions

Principals create school conditions that enable high-quality teaching and learning. Effective professional development programs and processes are essential for equipping principals with the knowledge and skills needed to create these conditions. Supports to keep them in the profession are also critical. However, continuing professional development and support for principals are often overlooked by districts and states, and, even when provided, may not be evidence based.

Licensing and certification systems represent entry-level knowledge and skills, and principals must continue with professional development across their careers in order to maintain licensure. While many states require a master’s degree to obtain licensure, this practice has not been supported by research. Licensure systems are linked to standards for effective school leadership preparation and development in all 50 states; the Professional Standards for Education Leaders represent the most current research on what is known about an effective principalship, and include emphases on creating equitable schools and inclusive and supportive school communities. In recent years, licensure assessment exams have been criticized as ineffective in predicting principal performance and biased against candidates of color. Transformative licensure assessment systems incorporate multiple methods of evaluating competencies, such as portfolios and performance-based assessments, and ensure these systems are bias-free and equitable.

High-quality principal induction simultaneously orients new principals to the school setting while strengthening their knowledge and skills through supportive structures. Effective induction programs, such as the one offered as part of the New Leaders’ Aspiring Principals Program, have been shown to improve principal retention and student achievement. Socialization is important for new principals to discuss challenges and successes with peers, and collaborative learning structures such as professional learning communities can support new learning as well as socialization.

Mentors and coaches for novice principals are essential aspects of high-quality induction programs. Mentors, who are usually experienced principals, share their expertise and encourage reflection by new principals as they face the challenges of school leadership; they also help new principals connect what they have learned in their preparation program to their new experiences on the job. While providing this job-embedded professional support, mentors themselves often benefit in multiple ways. Coaching and mentoring—in both induction and ongoing professional development—are solidly supported by research. Some districts are exploring shifting the role of principal supervisor to serve as coach rather than compliance officer, although further research is needed to determine this practice’s effectiveness. Important features of effective coaching and mentoring programs include a good match between mentor and mentee; formal selection and training of and compensation for mentors; and programs that extend beyond the first year of the principalship.

In-service professional development continues throughout the careers of principals as they seek to maintain licensure and ensure that their knowledge and skills are sufficient for addressing students’ needs in their particular school context. However, the professional development in which principals participate often is inconsistent with what is known about how adults learn best, and fails to provide the meaningful and authentic job-embedded learning and support shown to be effective. Coaching and mentoring, for example, are currently provided to only approximately half of the country’s principals despite being supported through high-quality research evidence. Principal networks and professional learning communities, which are more commonly used as a professional development strategy, offer principals a chance to form collegial relationships and learn from peers, as well as work together on common problems of practice.

While certain components of principal professional development such as coaching and mentoring are well supported by research, the field lacks rigorous research support as a whole. Several recent studies, however, have examined the effectiveness of comprehensive principal professional development programs using randomized designs that meet ESSA requirements for high-quality research, with mixed results. The National Institute for School Leadership Executive Development Program, for example, demonstrated improvements to student achievement as well as evidence of cost-effectiveness, while a program offered by the Center for Leadership at the University of Washington showed little impact on principal practice.

In conclusion, while research has highlighted the necessary components of principal professional development, evidence suggests that there is much room for improvement in developing licensure systems that provide an accurate gauge of whether a principal is ready to take on his or her new role, and in advancing induction and continued professional development programs that incorporate authentic, job-embedded learning.

Citations

Adams, J. E., Copland, M. A. (2005). When learning counts: Rethinking licenses for school leaders. Wallace Foundation. https://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/pub_crpe_learncounts_dec05_0.pdf

Alsbury, T. L., & Hackmann, D. G. (2006). Learning from experience: Initial findings of a mentoring/induction program for novice principals and superintendents. Planning and Changing, 37(3/4), 169–189.

Anderson, E., & Reynolds, A. (2015). The state of state policies for principal preparation program approval and candidate licensure. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 10(3), 193–221.

Bailes, L. P., & Guthery, S. (2020). Held down and held back: Systematically delayed principal promotions by race and gender. AERA Open, 6(2), 1–17.

Ballou, D., & Podgursky, M. (1995). What makes a good principal? How teachers assess the performance of principals. Economics of Education Review, 14(3), 243–252.

Bastian, K. C., & Henry, G. T. (2015). The apprentice: Pathways to the principalship and student achievement. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(4), 600–639.

Béteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2011). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes (Working Paper No. 17243). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w17243/w17243.pdf

Bickman, L., Goldring, E., De Andrade, A. R., Breda, C., & Goff, P. (2012, March). Improving principal leadership through feedback and coaching. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, Washington, DC. https://www.sree.org

Bloom, G., Castagna, C., Moir, E., & Warren, B. (Eds.). (2005). Blended coaching: Skills and strategies to support principal development. Corwin Press.

Browne-Ferrigno, T., & Muth, R. (2004). Leadership mentoring in clinical practice: Role socialization, professional development, and capacity building. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 468–494.

Burkhauser, S., Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., & Ikemoto, G. S. (2012). First-year principals in urban school districts: How actions and working conditions relate to outcomes. RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2012/RAND_TR1191.pdf

Canole, M., Young, M. D. (2013). Standards for educational leaders: An analysis. Council of Chief State School Officers.

Cheney, G. R., & Davis, J. (2011). Gateways to the principalship: State power to improve the quality of school leaders.Center for American Progress. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED535990.pdf

City, E. A., Elmore, R. F., Fiarman, S. E., & Teitel, L. (2009). Instructional rounds in education: A network approach to improving teaching and learning. Harvard Education Press.

Clifford, M., & Mason, C. (2013). Leadership for the Common Core: More than one thousand school principals respond. National Association of Elementary School Principals. https://www.naesp.org/sites/default/files/LeadershipfortheCommonCore_0.pdf

Coggshall, J. G. (2015). Title II, Part A: Don’t scrap it, don’t dilute it, fix it. Education Policy Center at American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Title%20II%2C%20Part%20A%20-%20Don%27t%20Scrap%20It%20Don%27t%20Dilute%20It%20Fix%20It.pdf

Daresh, J. C. (2007). Mentoring for beginning principals: Revisiting the past or preparing for the future? Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 20(4), 21–27. https://www.mwera.org/MWER/documents/MWER-2007-Fall-20-4.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr, M. T., & Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from exemplary leadership development programs. Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/preparing-school-leaders-changing-world-lessons-exemplary-leadership-development-programs_1.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., Meyerson, D., LaPointe, M., Orr, M. T. (2010). Preparing principals for a changing world: Lessons from effective school leadership programs. Jossey-Bass.

Davis, S., Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., & Meyerson, D. (2005). School leadership study: Developing successful principals. Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/school-leadership-study-developing-successful-principals.pdf

Davis, B. W., Gooden, M. A., & Bowers, A. J. (2017). Pathways to the principalship: An event history analysis of the careers of teachers with principal certification. American Educational Research Journal, 54(2), 207–240. https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=loOeLM4AAAAJ&hl=cs#d=gs_md_cita-d&u=%2Fcitations%3Fview_op%3Dview_citation%26hl%3Dcs%26user%3DloOeLM4AAAAJ%26citation_for_view%3DloOeLM4AAAAJ%3AqjMakFHDy7sC%26tzom%3D300

DeAngelis, K. J., & O’Connor, N. K. (2012). Examining the pipeline into educational administration: An analysis of applications and job offers. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 468–505.

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice, 56(1), 3–12.

Drago-Severson, E. (2008). 4 practices serve as pillars for adult learning. Journal of Staff Development, 29(4), 60-63. http://akrti2015.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/96476178/EDUCATOR%20EVALUATION%20HO6%20-%20PILLARS%20OF%20ADULT%20LEARNING.pdf

Drucker, K., Grossman, J., & Nagler, N. (2019). Still in the game: How coaching keeps leaders in schools and making progress [Policy brief]. NYC Leadership Academy. https://www.nycleadershipacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Still-in-the-Game-policy-brief.pdf

Dukess, L. (2001). Meeting the leadership challenge. Designing effective mentoring programs: The experiences of six New York City community school districts. New Visions for Public Schools.

Educational Testing Service. (2021). School leadership series: State requirements. https://www.ets.org/sls/states/

Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518–540.

Fuller, E., Hollingworth, L., & An, B. P. (2019). Exploring intersectionality and the employment of school leaders. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(2), 134–151.

Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., & Pendola, A. (2017). The Every Student Succeeds Act, state efforts to improve access to effective educators, and the importance of school leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(5), 727–756. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317199526_The_Every_Student_Succeeds_Act_State_Efforts_to_Improve_Access_to_Effective_Educators_and_the_Importance_of_School_Leadership

Fuller, E., & Young, M. D. (2009). Texas high school project leadership initiative issue brief 1: Tenure and retention of newly hired principals in Texas. University of Texas at Austin. https://www.casciac.org/pdfs/ucea_tenure_and_retention_report_10_8_09.pdf

Fusarelli, B. C., Fusarelli, L. D., & Riddick, F. (2018). Planning for the future: Leadership development and succession planning in education. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 13(3), 286–313.

Fusarelli, B. C., & Militello, M. (2012). Racing to the top with leaders in rural, high poverty schools. Planning and Changing, 43(1/2), 46–56. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ977546.pdf

Gates, S. M., Baird, M. D., Doss, C. J., Hamilton, L. S., Opper, I. M., Master, B. K., Tuma, A. P., Vuollo, M, & Zaber, M. A. (2019). Preparing school leaders for success: Evaluation of New Leaders’ Aspiring Principals Program, 2012–2017. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2812.html

Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., Martorell, P., Burkhauser, S., Heaton, P., Pierson, A., Baird, M., Vuollo, M., Li, J. J., Lavery, D. C., Harvey, M., & Gu, K. (2014). Preparing principals to raise student achievement: Implementation and effects of the New Leaders Program in ten districts. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR500/RR507/RAND_RR507.pdf

Goldrick, L. (2016). Support from the start; A 50-state review of policies on new educator induction and mentoring. New Teacher Center. https://newteachercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016CompleteReportStatePolicies.pdf

Goldring, E., Porter, A., Murphy, J., Elliott, S., Cravens, X. (2009). Assessing learning-centered leadership: Connections to research, professional standards, and current policies. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(1), 1–36. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Assessing-Learning-Centered-Leadership.pdf

Goldring, R., & Taie, S. (2014). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 principal follow-up survey (NCES 2014-064 rev). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2014064rev

Goldring, R., & Taie, S. (2018). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2016–17 principal follow-up survey (NCES 2018-066). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018066.pdf

Gordon, S. P. (2020). The principal development pipeline: A call for collaboration. NASSP Bulletin, 104(2), 61–84.

Gordon, S. P., & Niemiec, J. (2020). State assessment for principal licensure: Traditional, transitional, or transformative? International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 15(1), 107–125. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1254598.pdf

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. Wallace Foundation. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/How-Principals-Affect-Students-and-Schools.pdf

Grissom, J. A., & Harrington, J. R. (2010). Investing in administrator efficacy: An examination of professional development as a tool for enhancing principal effectiveness. American Journal of Education, 116(4), 583–612.

Grissom, J. A., Mitani, H., & Blissett, R. S. L. (2017). Principal licensure exams and future job performance: Evidence from the school leaders licensure assessment. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(2), 248–280.

Grissom, J. A., Mitani, H., & Woo, D. S. (2019). Principal preparation programs and principal outcomes. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(1), 73–115.

Hackmann, D. G. (2016). Considerations of administrative licensure, provider type, and leadership quality: Recommendations for research, policy, and practice. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(1), 43–67.

Hall, P. (2008). Building bridges: Strengthening the principal induction process through intentional mentoring. Phi Delta Kappan, 89(6), 449–452.

Haller, E. J., Brent, B. O., & McNamara, J. H. (1997). Does graduate training in educational administration improve America’s schools? Phi Delta Kappan, 79(3), 222–227.

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010). Leadership for learning: Does collaborative leadership make a difference in school improvement? Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 38(6), 654–678.

Hansford, B. and Ehrich, L. C. (2006) The principalship: How significant is mentoring?. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(1), 36–52.

Herman, R., Gates, S. M., Arifkhanova, A., Barrett, M., Bega, A., Chavez-Herrerias, E. R., Han, E., Harris, M., Migacheva, K., Ross, R., Leschitz, & Wrabel, S. L. (2017). School leadership interventions under the Every Student Succeeds Act: Evidence review. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1500/RR1550-3/RAND_RR1550-3.pdf

Hermann, M., Clark, M., James-Burdumy, S., Tuttle, C., Kautz, T., Knechtel, V., Dotter, D., Wulsin, C. S., & Deke, J. (2019). The effects of a principal professional development program focused on instructional leadership (NCEE 2020-0002). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED599489.pdf

Hitt, D. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 531–569.

Ikemoto, G., Taliaferro, L., Fenton, B., & Davis, J. (2014). Great principals at scale: Creating district conditions that enable all principals to be effective. Bush Institute and New Leaders. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED556346.pdf

Jacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL Balanced Leadership Program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332.

Klar, H. W., & Huggins, K. S. (2020). Developing rural school leaders: Building capacity through transformative leadership coaching. Routledge.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., III, & Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588.

Lashway, L. (2003). Inducting school leaders. ERIC Digest. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED479074.pdf

Lavigne, H. J., Shakman, K., Zweig, J., & Greller, S. L. (2016). Principals’ time, tasks, and professional development: An analysis of Schools and Staffing Survey data (REL 2017-201). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/northeast/pdf/REL_2017201.pdf

Lee, O. Z. (2010). The leadership gap: Preparing leaders for urban schools (UMI No. 304932769) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership and Management, 40(1), 5–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332530133_Seven_strong_claims_about_successful_school_leadership_revisited

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turnaround: How successful school leaders transform low-performing schools. John Wiley & Sons.

Levin, S., Leung, M., Edgerton, A. K., & Scott, C. (2020). Elementary school principals’ professional learning: Current status and future needs [Research brief]. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/NAESP_Elementary_Principals_Professional_Learning_BRIEF.pdf

Lewis, L., & Scott, J. (2020). Principal professional development in U.S. public schools in 2017-18 (NCES 2020-045). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020045.pdf

Lochmiller, C. R. (2014). Leadership coaching in an induction program for novice principals: A 3-year study. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 9(1), 59–84.

Manna, P. (2015). Developing excellent school principals to advance teaching and learning: Considerations for state policy. Wallace Foundation. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Developing-Excellent-School-Principals.pdf

McREL International. (2021). Balanced leadership. https://www.mcrel.org/balancedleadership/

Mendels, P. (Ed.). (2016). Improving university principal preparation programs: Five themes from the field. Wallace Foundation. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Improving-University-Principal-Preparation-Programs.pdf

Miller, R. J., Goddard, R. G., Kim, M., Jacob, R., Goddard, Y., & Schroeder, P. (2016). Can professional development improve school leadership? Results from a randomized control trial assessing the impact of McREL’s Balanced Leadership Program on principals in rural Michigan schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(4), 531–566.

National Policy Board for Educational Administration (2015). Professional Standards for Educational Leaders 2015. https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/ProfessionalStandardsforEducationalLeaders2015forNPBEAFINAL.pdf

Nunnery, J. A., Ross, S. M., Chappell, S., Pribesh, S., & Hoag-Carhart, E. (2011). The impact of the NISL Executive Development Program on school performance in Massachusetts: Cohort 2 results. Old Dominion University, Center for Educational Partnerships. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED531042.pdf

Nunnery, J. A., Yen, C., & Ross, S. M. (2010). Effects of the National Institute for School Leadership’s Executive Development Program on school performance in Pennsylvania: 2006–2010 pilot cohort results. Old Dominion University, Center for Educational Partnerships. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED531043.pdf

NYC Leadership Academy. (n.d.). Giving new principals a strong start: What works in principal induction. https://www.nycleadershipacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/principal-induction-leadership-brief.pdf

Oplatka, I., & Lapidot, A. (2018). Novice principals’ perceptions of their mentoring process in early career stage: The key role of mentor-protégé relations. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 50(3), 204–222.

Orr, M. T., Pecheone, R., Snyder, J. D., Murphy, J., Palanki, A., Beaudin, B., Hollingworth, L., & Buttram, J. L. (2018). Performance assessment for principal licensure: Evidence from content and face validation and bias review. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 13(2), 109–138.

Psencik, K., & Brown, F. (2018). Learning to lead: Districts collaborate to strengthen principal practices. Learning Professional, 39(3), 48–53. https://learningforward.org/journal/june-2018-vol-38-no-3/learning-to-lead-districts-collaborate-to-strengthen-principal-practices/

Rainey, L. R., & Honig, M. L. (2015). From procedures to partnerships: Redesigning principal supervision to help principals lead for high-quality teaching and learning. University of Washington Center for Educational Leadership. http://www.nysed.gov/common/nysed/files/file-22-from-procedures-to-partnership-redesigning-principal-supervision-2015.pdf

Riley, D. L., & Meredith, J. (2017). State efforts to strengthen school leadership: Insights from CCSSO action groups. Policy Studies Associates. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED580215.pdf

Roach, V., Smith, L. W. & Boutin, J. (2011). School leadership policy trends and development: Policy expediency or policy excellence? Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(1), 71–113.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on school outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674.

Rowland, C. (2017). Principal professional development: New opportunities for a renewed state focus. Education Policy Center at American Institutes for Research. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED582417.pdf

School Leaders Network. (2014). Churn: The high cost of principal turnover. https://www.acesconnection.com/fileSendAction/fcType/0/fcOid/405780286632981504/filePointer/405780286632981536/fodoid/405780286632981531/principal_turnover_cost.pdf

Scott, D. (2017). 2017 State policy review: School and district leadership. Education Commission of the States.https://www.ecs.org/2017-state-policy-update-school-and-district-leadership/

Scott, D. (2018). 50-state comparisons: School leader certification and preparation programs. Education Commission of the States. https://www.ecs.org/50-state-comparison-school-leader-certification-and-preparation-programs/

Shoho, A. R., & Barnett, B. G. (2010). The realities of new principals: Challenges, joys and sorrows. Journal of School Leadership, 20(5), 561–596.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330574331_The_Realities_of_New_Principals_Challenges_Joys_and_Sorrows

Simon, S., Dole, S., & Farragher, Y. (2019). Custom-designed and safe-space coaching: Australian beginning principals supported by experienced peers form pipeline of confident future leaders. School Leadership and Management,39(2), 145–174.

Southern Regional Education Board. (2007). Good principals aren’t born—they’re mentored: Are we investing enough to get the school leaders we need? https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Good-Principals-Arent-Born-Theyre-Mentored.pdf

Steinberg, M. P., & Yang, H. (2020). Does principal professional development improve principal persistence, teacher effectiveness, and student achievement? Evidence from Pennsylvania’s Inspired Leadership Induction Program(EdWorkingPaper 20-190). Annenberg Institute at Brown University.https://edworkingpapers.org/sites/default/files/ai20-190.pdf

Supovitz, J., Sirinides, P., & May, H. (2010). How principals and peers influence teaching and learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 31–56.

Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Supporting principals’ learning: Key features of effective programs. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Supporting_Principals_Learning_REPORT.pdf

Taie, S., & Goldring, R. (2017). Characteristics of public elementary and secondary school principals in the United States: Results from the 2015–16 National Teacher and Principal Survey, First Look (NCES 2017-070). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017070.pdf

Taie, S., & Goldring, R. (2019). Characteristics of Public and Private Elementary and Secondary School Principals in the United States: Results From the 2017–18 National Teacher and Principal Survey, First Look (NCES 2019-141). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019141.pdf

Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P., III. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293. https://education.ufl.edu/villarreal/files/2011/10/Leadership-and-Policy-Villarreal.pdf

Turnbull, B. J., Riley, D. L., & MacFarlane, J. R. (2013). Cultivating talent through a principal pipeline. Policy Studies Associates. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Building-a-Stronger-Principalship-Vol-2-Cultivating-Talent-in-a-Principal-Pipeline.pdf

U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Findings from the 2014–2015 Survey on the Use of Funds Under Title II, Part A. https://www2.ed.gov/programs/teacherqual/learport.pdf

Valentine, J. W., & Prater, M. (2011). Instructional, transformational, and managerial leadership and student achievement: High school principals make a difference. NASSP Bulletin, 95(1), 5–30.

Villani, S. (2006). Mentoring and induction programs that support new principals. Corwin Press.

Vogel, L., & Weiler, S. C. (2014). Aligning preparation and practice: An assessment of coherence in state principal preparation and licensure. NASSP Bulletin, 98(4), 324–350.

Wallace Foundation. (2007). Educational leadership: A bridge to school reform. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Bridge-to-School-Reform.pdf

Wallace Foundation. (2008). Becoming a leader: Preparing school principals for today’s schools. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Becoming-a-Leader-Preparing-Principals-for-Todays-Schools.pdf

Wallace Foundation. (2011). Research findings to support effective educational policies: A guide for policymakers (2nd ed). https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Findings-to-Support-Effective-Educational-Policy-Making.pdf

Wallace Foundation. (2013). The school principal as leader: Guiding schools to better teaching and learning. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/overview-the-school-principal-as-leader.aspx

Wang, E. L., Schwartz, H. L., Mean, M., Stelitano, L., & Master, B. K. (2019). Putting professional learning to work: What principals do with their Executive Development Program learning. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3082.html

Waters, T., Marzano, R. J., McNulty, B. A. (2003). Balanced leadership: What 30 years of research tells us about the effect of leadership on student achievement. McREL International. https://www.mcrel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Balanced-Leadership®-What-30-Years-of-Research-Tells-Us-about-the-Effect-of-Leadership-on-Student-Achievement.pdf

Wise, D., & Jacobo, A. (2010). Towards a framework for leadership coaching. School Leadership and Management, 30(2), 159–169.

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement (REL 2007–No. 033). U.S. Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/southwest/pdf/rel_2007033_sum.pdf

Young, I. P., Vang, M., & Young, K. H. (2008). Effects of student characteristics, principal qualifications, and organizational constraints for assessing student achievement: A school public relations and human resources concern. Journal of School Public Relations, 29(3), 378–400.

Zepeda, S. J. (2013). Professional development: What works (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Adapted from Lewis and Scott, 2020

Adapted from Lewis and Scott, 2020