Professional Judgment Overview

Overview of Professional Judgment PDF

Guinness, K., and Detrich, R. (2021). Overview of Professional Judgment. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/evidence-based-decision-making-professional-judgment.

Introduction

Every educational situation is unique based on concerns, setting, and student and teacher needs. Educators must rely on the best available evidence at decision-making time, but even the strongest evidence will not match the situation exactly. An inferential leap is required when implementing an evidence-based practice (EBP) described in empirical literature in an applied setting. When making this inferential leap, educators use professional judgment (also called professional wisdom or professional expertise), a “personal process that actually guides scientist and practitioner behavior in controversial and ambiguous circumstances” (Barnett, 1988, p. 658), to adapt the EBP to their specific situation.

Developing Professional Judgment

Educators develop professional judgment over the course of their careers, yet they can take active steps to facilitate this development. Slocum et al. (2014) described the following key components of clinical expertise for behavior analysts, which can also apply to educators.

Familiarity With the Research Literature

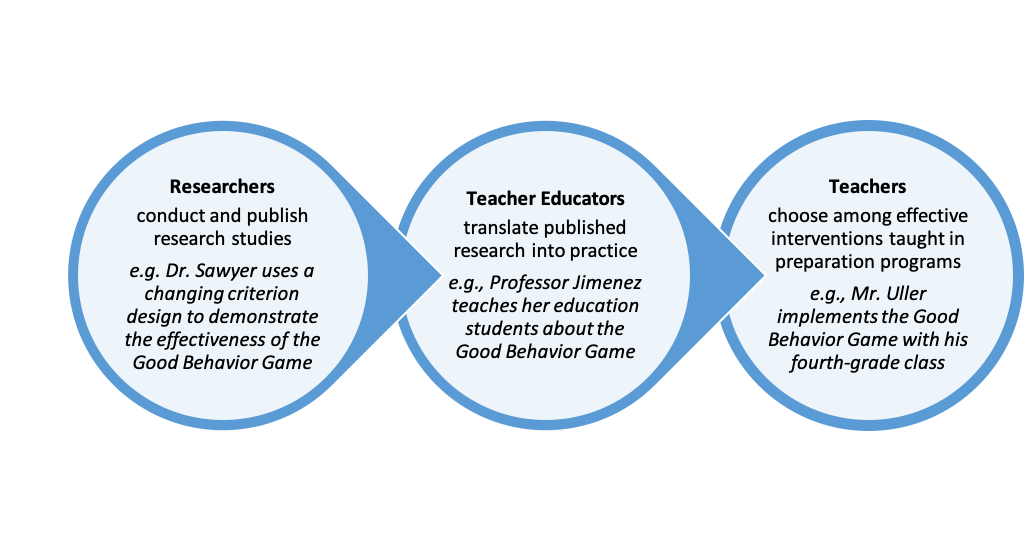

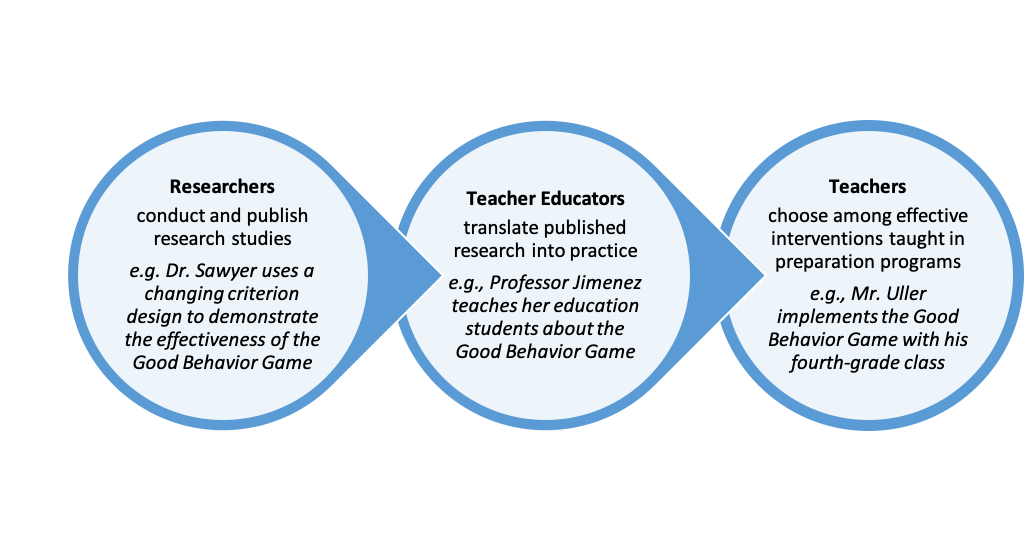

One cornerstone of EBP is reliance on best available evidence, which involves synthesizing the results of multiple research studies. Perhaps the most important barrier to locating and interpreting empirical research is that science is not easy. Landrum and Tankersley (2004) emphasized that teachers generally are not trained to interpret research, but “the educational enterprise becomes inefficient to the extent that practitioners must... always return to the research literature to answer every question they encounter about instruction or intervention” (p. 211). Delineating how researchers, teacher educators, and teachers play different roles in working toward the same goal of effective education can be helpful; for an example, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Suggested delineation of roles for researchers, teacher educators, and teachers in achieving effective education

Understanding Conceptual Systems

Individual applications of EBPs can vary widely, and educators will inevitably make adaptations to fit their current situation. When considering adaptations, educators should ensure they understand why an EBP works and can distinguish between core and peripheral components (Harn et al., 2013; Leko, 2015). Modifying a core component, such as the method or amount of instruction, may impact the effectiveness of the intervention. Modifying a peripheral component, such as the type of reward provided, is discretionary and likely will not negatively impact effectiveness. Distinguishing between core and peripheral components is challenging in practice, as determining which components of an intervention are responsible for its effectiveness requires a component analysis. Therefore, educators must rely on identifying the kernel (Embry & Biglan, 2008) or practice element (Chorpita et al., 2007); that is, components of behavioral influence derived from experimental research.

Incorporating Stakeholder Values and Context

Stakeholders can include caregivers, school leadership, community members, and the students themselves. When informing caregivers about their educational rights under the Individuals With Disabilities Act (IDEA), special educators can use the opportunity to provide information about EBP and include caregivers in the decision-making process (Cook et al., 2021). Context includes the environment in which the intervention will be implemented (physical environment, group size, student-to-teacher ratio) and the available resources (funds, training time, materials and supplies). Professional judgement is required to incorporate stakeholders and context.

Recognizing the Need for Outside Consultation

An educator may be experienced in implementing classroom management strategies in a general education setting, perhaps within Tier 1 of a multitiered system of support (MTSS). However, if some students do not respond to this intervention, additional support may be needed; this can be facilitated through consultation with an interdisciplinary team. Part of professional judgment is recognizing when one does not have the training, experience, or competency for a particular problem or context.

Data-Based Decision Making

When an EBP is adapted, progress monitoring is critical to ensuring the effectiveness of the program. Evaluating the data requires judgment: Should the intervention continue, should it be modified, or should it be terminated? Curriculum-based measurement involves developing a measurement system that is reliable and valid, simple and efficient, easy to understand, and inexpensive (Deno, 1985). One example is the number of words read correctly per minute. When assessing student performance, consistency is key to ensuring reliable measurement and fair comparison over time. Consistency in the materials and instructions provided, the timing of the assessment, and how the assessment is scored are necessary (Stecker et al., 2008). A reliable measurement system allows educators to trust the data and use their professional judgment to make data-informed decisions.

Ongoing Professional Development

An educator’s professional judgment constantly evolves. Just as the best available evidence changes as new research is published, professional judgment is refined through continual professional development (see Teacher Professional Development). Gesel et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of the effects of professional development on teacher knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy in using curriculum-based measurement and data-based decision making. Professional development activities included offering repeated practice opportunities, providing automatic graphing software or individualized student progress reports, and applying decision rules. Moderate effect sizes were observed, but the researchers noted that most studies included in the analysis took place under ideal conditions with a high degree of researcher support. Additional research is needed on the sustained effects of professional development in applied settings.

Using Professional Judgment to Adapt Evidence-Based Practices

When selecting and adapting an evidence-based practice, Cook et al. (2008) concluded that educators must consider several factors: student needs, educator strengths, and educational context.

Student Needs

Individual students can have a wide variety of learning and motivational needs. Zriebec Uberti et al. (2004) described a case example in which a special education teacher created individualized self-instruction checklists to teach a math strategy to students with learning disabilities and English as a second language. The teacher based each checklist on the student’s specific errors during an initial assessment; for example, one student’s checklist emphasized writing numerals in the appropriate columns while another’s contained reminders about when to carry and add 1. The teacher provided the students with their individualized checklists as the class worked on math problems and provided stickers for correctly using the checklist; these could later be exchanged for a reward. The participants’ posttest scores (averaging 90%) were considerably higher than pretest scores (averaging 31%). In this example, the teacher used professional judgment to adapt the intervention (self-instruction checklists) for each student as opposed to providing a generic checklist to all students.

Educator Strengths

When educators consider implementing an evidence-based practice, their own familiarity with the intervention can greatly affect implementation, including decisions about making adaptations. Webster-Stratton et al. (2011) described how The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management (IY TCM) training incorporated flexible elements that could be adapted based on teacher needs. The pacing of instruction was set by the teacher; a slower pace was recommended for teachers less experienced in classroom management. The IY TCM manual included a wide variety of vignettes, discussion questions, and other activities. The group facilitator could select the activities most relevant to their group and include more activities as needed.

Leko et al. (2015) interviewed five middle school teachers and found that they used their professional judgement to adapt a commercially available language arts curriculum (System 44) based on three factors: individual student needs, contextual fit, and their own teaching characteristics. Only one teacher had ever used System 44. Even after initial professional development, the participants were learning the curriculum on the job. The researchers found that participants supplemented the curriculum with skills that they believed were important but that System 44 did not cover. One teacher focused on note taking and whole group instruction while another prioritized working independently. The teachers’ experiences, strengths, and preferences influenced how they modified the curriculum. It should be noted that this was a qualitative study to explore the types of adaptations made and teacher-reported rationales and did not directly measure the effects of adaptation on outcomes.

Educational Context

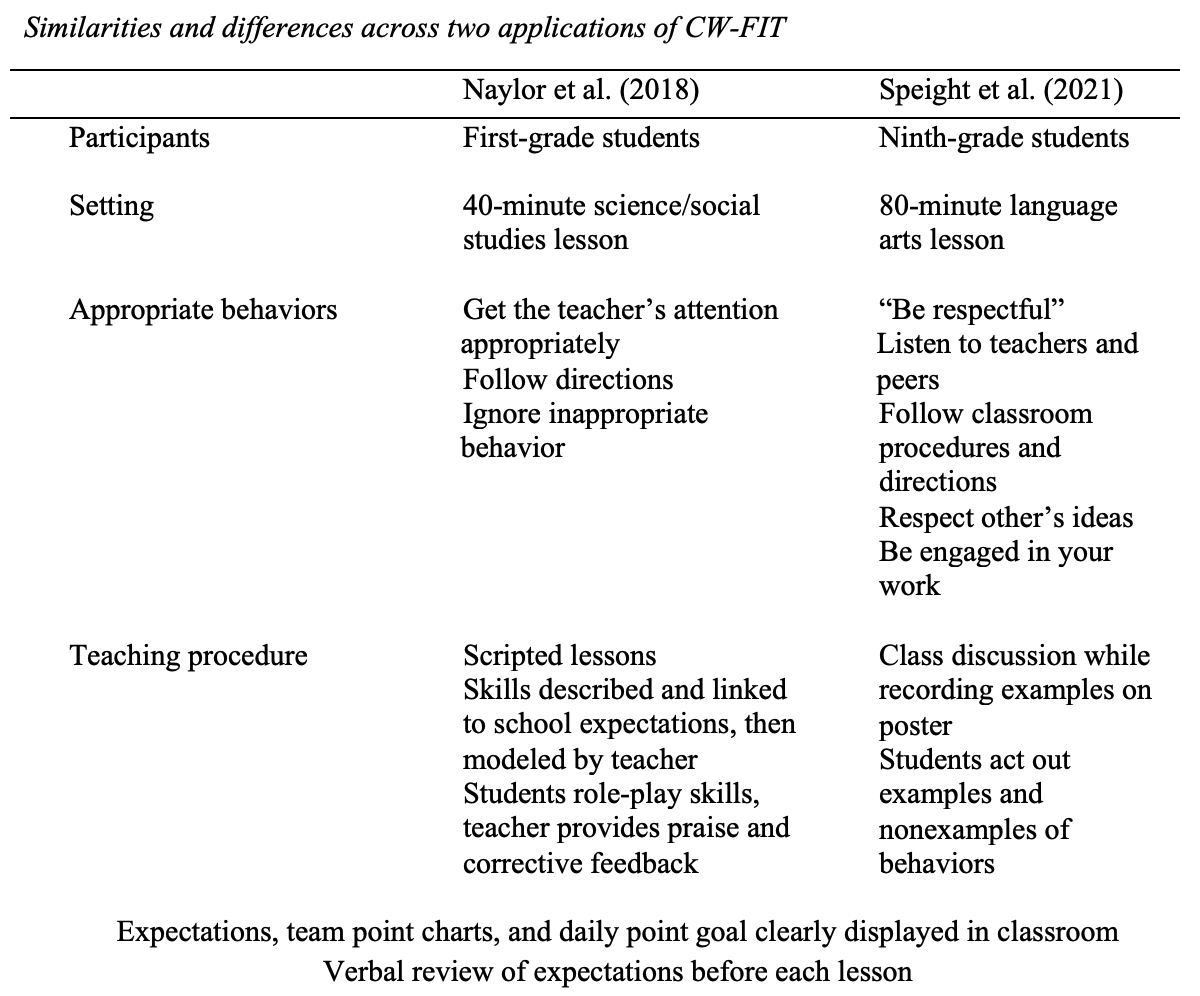

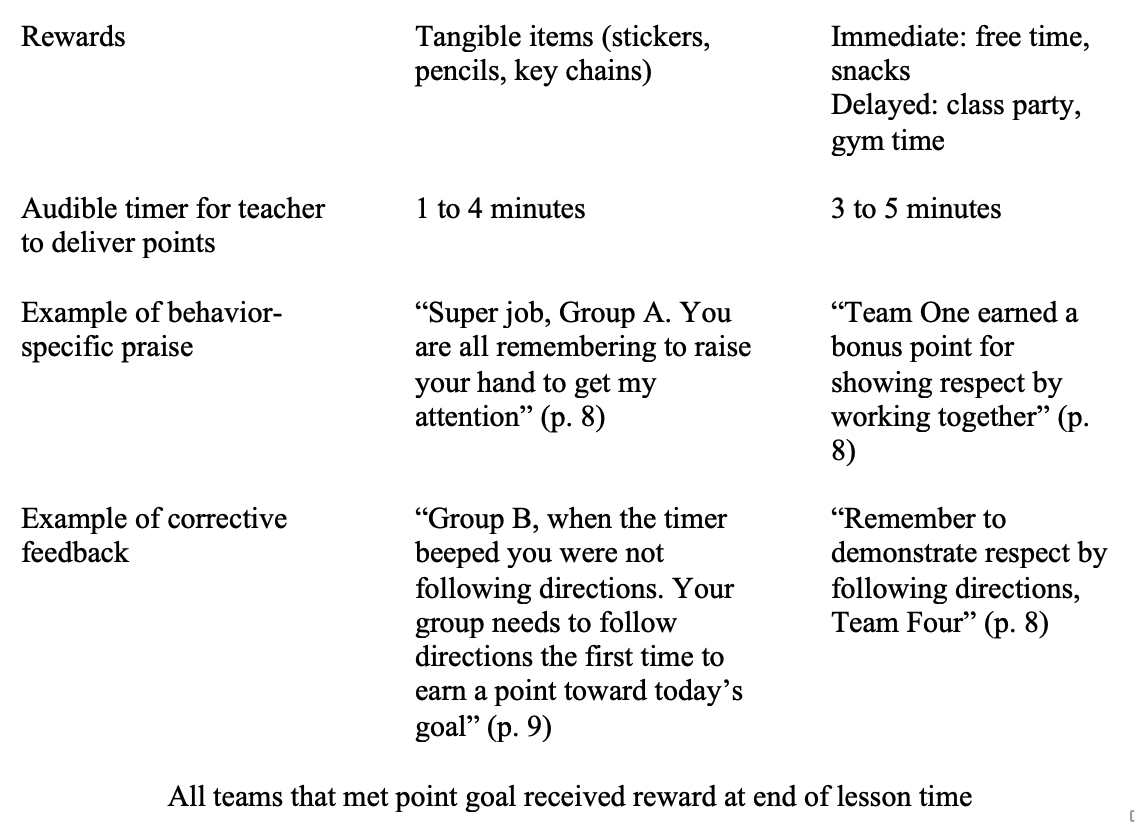

The environment or context in which the intervention will be implemented must be considered. Class-Wide Function-Related Intervention Teams (CW-FIT) is an intervention package that includes teaching appropriate replacements to challenging behavior, reviewing skills prior to each lesson, and providing rewards within a group contingency. Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CW-FIT in general and special education elementary classrooms (e.g., Kamps et al., 2015; Naylor et al., 2018; Wills et al., 2018).

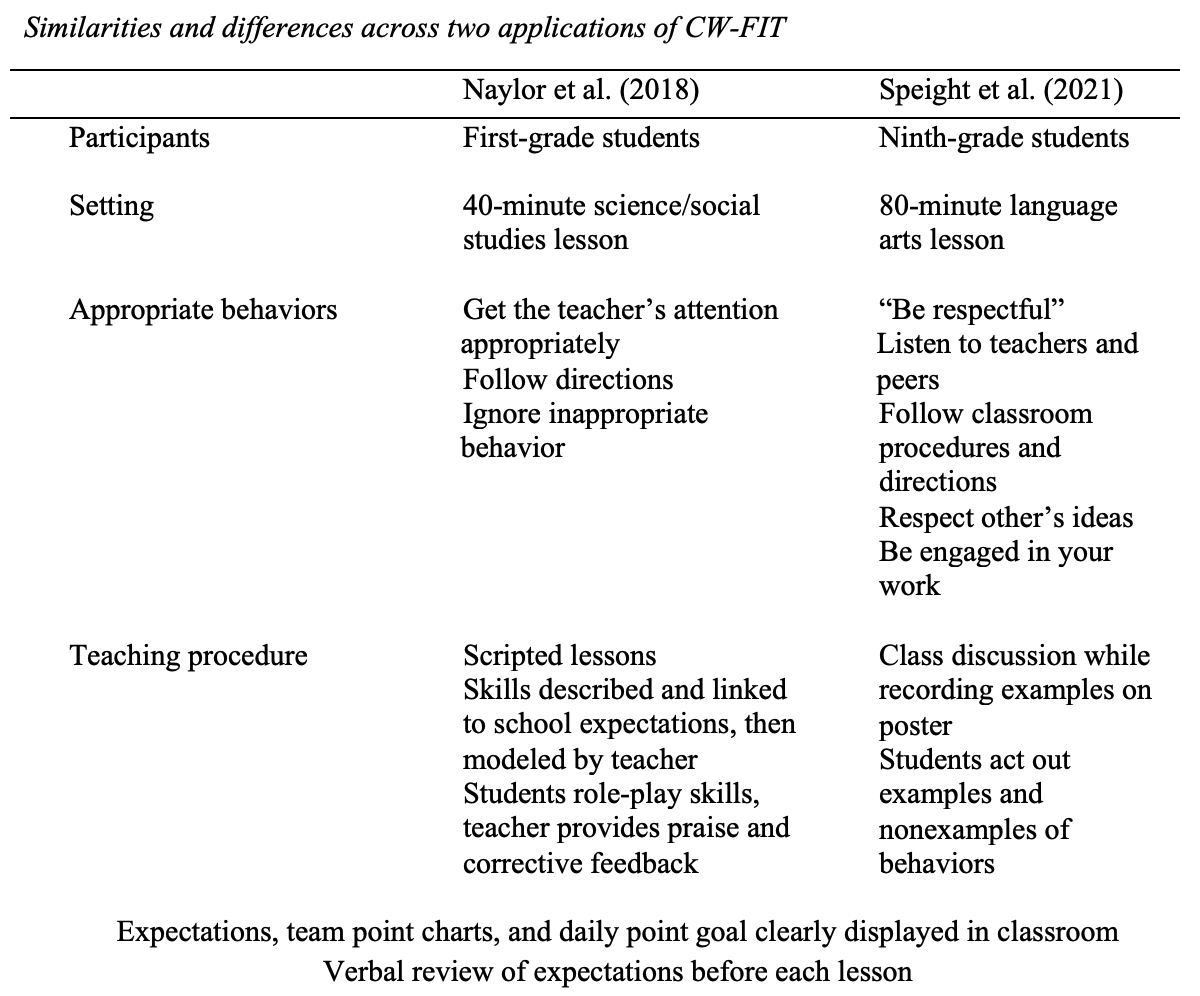

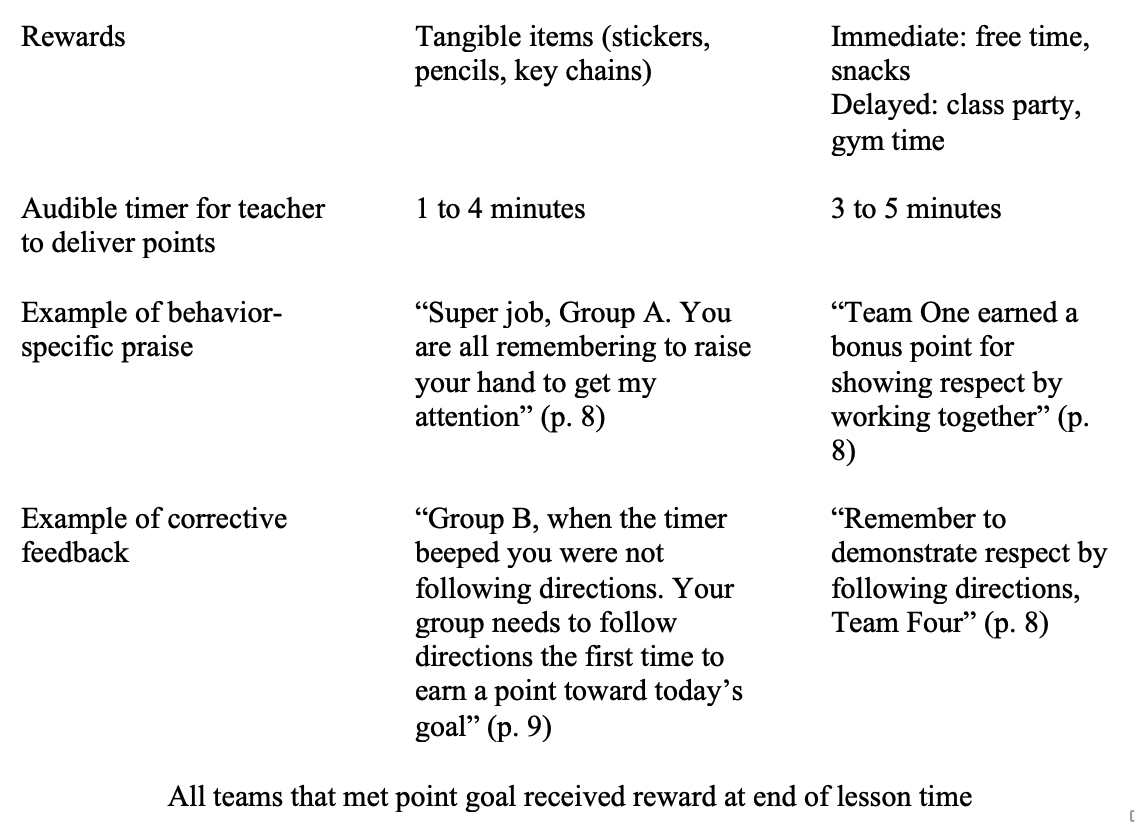

A recent study by Speight et al. (2021) evaluated the effects of CW-FIT on student and teacher behavior in a high school classroom. Peripheral components of the intervention were adapted for this specific context: for example, larger, delayed rewards more appropriate for older students, such as a class party, were included. Table 1 depicts the similarities and differences between two applications of CW-FIT in different contexts. Note how the core components are the same, but peripheral components (type of reward, specific appropriate behaviors, duration of lesson) varied. In each case, the researchers used professional judgment to adapt the intervention based on the context but maintained the core components responsible for the effectiveness of the intervention.

Table 1

What Adaptations Are Educators Making and Why?

Parekh et al. (2019) evaluated the extent to which teachers made adaptations to an evidence-based sexual health curriculum and the effects of adaptations on outcomes. Program facilitators completed a log detailing changes they had made to the program after each program session. Overall, the average level of adaptation was 63% (ranging from 3% to 98%). The most common adaptation was increasing the amount of time to complete the program; it was designed to be completed in 8 hours, but study participants completed it in an average of 11 hours.

The researchers divided the participants into three categories: low adaptation (<25%), moderate adaptation (25% to 50%), and high adaptation (>50%). On outcome measures such as sexual health knowledge, intent to abstain from sex, and intent to use birth control, all three categories of participants had significantly better outcomes than comparison groups that did not receive the intervention. Further, there were no differences among the three adaptation levels, suggesting that adaptation did not impact outcomes. Importantly, the authors noted “the type of adaptations suggest that program implementers were not making changes to core content of the program, but rather were making changes in the delivery of the content such as dosage, [and] modality...as a response to classroom context and participant needs/behavior” (p. 1080). In this example, adaptations were made to peripheral rather than core components, which could account for the maintenance of effectiveness despite reduced adherence.

Kern et al. (2020) examined 19 published studies on social skills training. Among them were 8 studies that made adaptations; 6 of the 8 made adaptations at the outset of the study while the remaining 2 made adaptations based on student nonresponse. The most common adaptations were matching lessons to participant skill deficits and adding a token economy. Other types of adaptations included using peers, self-monitoring, and changing the session time. Rationales for adaptations included data-based (formal assessment or baseline data collection), clinical judgment (no formal data collection), and nonresponse, but the most common rationale was not data-based but rather a priori (i.e., a modification was made prior to implementation as part of a replication or research study). The studies that reported adaptations resulted in favorable outcomes, yet it is unclear if the adaptations were necessary to achieve these outcomes. More research on the direct effects of adaptations on intervention effectiveness is needed.

Professional Judgment Over Time

More experienced professionals are often assumed to have better professional judgment, but that is not necessarily the case. Choudhry et al. (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of studies examining the relation between physicians’ clinical experience and quality of patient care. They found that clinical experience was inversely related to quality of care—that is, physicians with more years of experience had lower quality of patient care. There are a couple of potential explanations for this: Older, more experienced physicians may be less likely to participate regularly in professional development, or they may not be trained in more recent therapies that were researched after their initial training. This analysis was based on research with physicians, and additional research is needed on the relation between experience and professional judgment with educators. Yet the findings highlight the need for continual professional development to stay informed of the best available evidence.

Conclusions and Implications

Professional judgment is a key component of evidence-based practice, and educators use professional judgment to adapt EBPs to their specific situation. An individual’s professional judgment evolves with the best available evidence. Continual professional development on EBPs, data-based decision making, and recognizing the need for outside consultation is integral to this process. When considering adaptations for EBPs, educators should ensure they understand why the intervention works, and modify peripheral components rather than core components. Distinguishing which components are core versus peripheral can be challenging, but identifying the fundamental elements of behavioral influence, or kernels, can serve as a starting point (Embry & Biglan, 2008).

In practice, educators frequently make adaptations, although more research is needed on the effects of adaptation on outcome measures. Adaptations may be based on student needs, educator strengths, or the educational context. Ultimately, whatever the adaptation, progress monitoring and data-based decision making are vital to ensuring that the most effective intervention is delivered to students.

Citations

Barnett, D. W. (1988). Professional judgment: A critical appraisal. School Psychology Review, 17(4), 658–672.

Chorpita, B. F., Becker, K. D., & Daleiden, E. L. (2007). Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(5), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e318033ff71

Choudhry, N. K., Fletcher, R. H., & Soumerai, S. B. (2005). Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(4), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008

Cook, B. G., Shepherd, K. G., Cook, S. C., & Cook, L. (2021). Facilitating the effective implementation of evidence-based practices through teacher-parent collaboration. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44(3), 22–30.

Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., & Harjusola-Webb, S. (2008). Evidence-based special education and professional wisdom: Putting it all together. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451208321566

Deno, S. L. (1985). Curriculum-based measurement: The emerging alternative. Exceptional Children, 52(3), 219–232.

Embry, D. D., & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 75–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x

Gesel, S. A., LeJeune, L. M., Chow, J. C., Sinclair, A. C., & Lemons, C. J. (2021). A meta-analysis of the impact of professional development on teachers’ knowledge, skill, and self-efficacy in data-based decision-making. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 54(4), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420970196

Harn, B., Parisi, D., & Stoolmiller, M. (2013). Balancing fidelity with flexibility and fit: What do we really know about fidelity of implementation in schools? Exceptional Children, 79(3), 181–193.

Kamps, D., Wills, H., Dawson-Bannister, H., Heitzman-Powell, L., Kottwitz, E., Hansen, B., & Fleming, K. (2015). Class-Wide Function-Related Intervention Teams “CW-FIT” efficacy trial outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(3), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300714565244

Kern, L., Gaier, K., Kelly, S., Nielsen, C. M., Commisso, C. E., & Wehby, J. H. (2020). An evaluation of adaptations made to Tier 2 social skills training programs. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 36(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2020.1714858

Landrum, T. J., & Tankersley, M. (2004). Science in the schoolhouse: An uninvited guest. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(3), 207–212.

Leko, M. M. (2015). To adapt or not to adapt: Navigating an implementation conundrum. Teaching Exceptional Children, 48(2), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059915605641

Leko, M. M., Roberts, C. A., & Pek, Y. (2015). A theory of secondary teachers’ adaptations when implementing a reading intervention program. Journal of Special Education, 49(3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466914546751

Naylor, A. S., Kamps, D., & Willis, H. (2018). The effects of the CW-FIT group contingency on class-wide and individual behavior in an urban first grade classroom. Education and Treatment of Children, 41(1), 1–30.

Parekh, J., Stuart, E., Blum, R., Caldas, V., Whitfield, B., & Jennings, J. M. (2019). Addressing the adherence-adaptation debate: Lessons from the replication of an evidence-based sexual health program in school settings. Prevention Science, 20(7), 1074–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01032-2

Slocum, T. A., Detrich, R., Wilczynski, S. M., Spencer, T. D., Lewis, T., & Wolfe, K. (2014). The evidence-based practice of applied behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst, 37(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-014-0005-2

Speight, R., Kucharczynk, S., & Whitby, P. (2021). Effects of a behavior management strategy, CW-FIT, on high school student and teacher behavior. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-020-09428-9

Stecker, P. M., Lembke, E. S., & Foegen, A. (2008). Using progress-monitoring data to improve instructional decision making. Preventing School Failure, 52(2), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.3200/PSFL.52.2.48-58

Webster-Stratton, C., Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Newcomer, L. L. (2011). The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management training: The methods and principles that support fidelity of training delivery. School Psychology Review, 40(4), 509–529.

Wills, H., Wehby, J., Caldarella, P., Kamps, D., Swinburne Romine, R. (2018). Classroom management that works: A replication trial of the CW-FIT program. Exceptional Children, 84(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402918771321

Zrebiec Uberti, H., Matropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (2004). Check it off: Individualizing a math algorithm for students with disabilities via self-monitoring checklists. Intervention in School and Clinic, 39(5), 269–275.