Teacher Retention Analysis

Teacher Retention Analysis Overview PDF

Donley, J., Detrich, R. Keyworth, R., & States, J., (2019). Teacher Retention Analysis Overview. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/teacher-retention-turnover-analysis.

Failure to retain teachers has been a persistent problem in the United States over the past 25 years. Teacher turnover has contributed to a short supply of qualified teachers in certain locations (e.g., high-poverty urban and rural communities), in particular subject areas (e.g., science, technology, engineering, and math [STEM] courses), and among certain student groups (e.g., special education students) (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2019). These shortages have led to an inequitable distribution of high-quality teachers and poor outcomes for the students most in need of consistent high-quality instruction (Goldhaber, Gross, & Player, 2011; Goldhaber, Lavery, & Theobald, 2015; Hanushek, Kain, & Rivken, 2004). Teacher turnover is also quite costly (Barnes, Crowe, & Schaefer, 2007; Synar & Maiden, 2012), and has been shown to disrupt student learning and lower student achievement (Henry & Redding, in press; Ronfeldt, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2013) as well as contribute negatively to teacher working conditions (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010; Ingersoll, 2001; Simon & Johnson, 2015). Keeping effective teachers in classrooms is a key ingredient necessary for school improvement and positive and equitable student outcomes. This report analyzes the retention problem in the United States through documentation of recent teacher turnover data, and reviews the research on the factors that contribute to teachers’ decisions to remain in the classroom.

The Problem of Teacher Turnover

Teacher turnover, defined as “change in teachers from one year to the next in a particular school setting” (Sorenson & Ladd, 2018, p. 1), has been a persistent problem often described as a revolving door in the teaching profession (Ingersoll, 2003). Teacher turnover includes teachers who move to a different school (“movers”) and those who either leave the profession to retire or leave voluntarily prior to retirement (“leavers”) (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Movers and leavers together represent the degree of “churn” in the teacher workforce (Atteberry, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2017; Ingersoll Merrill, Stuckey, & Collins, 2018), while leavers considered separately represent the rate of attrition in the workforce. Rates of churn vary greatly across states, districts, and schools, and across subject areas and student populations (Papay, Bacher-Hicks, Page, & Marinell, 2017; Redding & Henry, 2018). A discussion of recent descriptive data is provided next, followed by an analysis of the factors that contribute to teacher turnover.

Figure 1 shows that teacher turnover rates in the United States have hovered around 16% over the last 10 years for which data are available (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014).

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey” (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014).

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey” (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014).

Figure 1. Percentage of public school teacher movers and leavers, 1988–1989 through 2012–2013

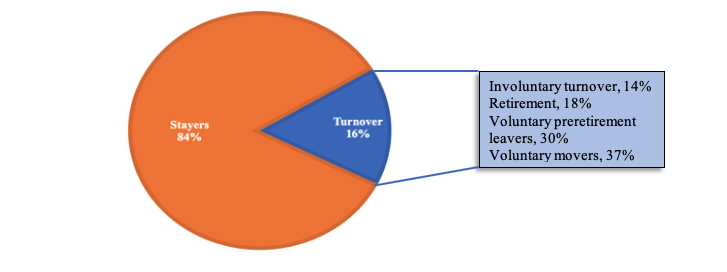

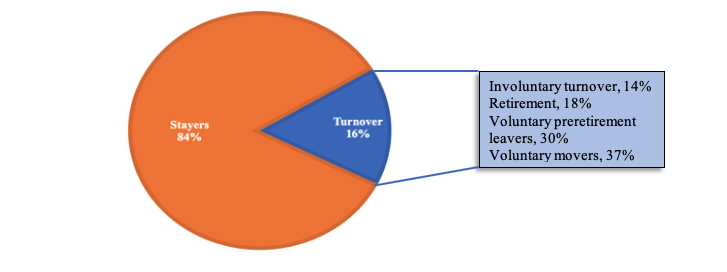

While the percentage of movers has remained fairly consistent across 25 years of the study, the percentage of leavers increased substantially from 1991–1992 and peaked in 2004–2005, suggesting increasing problems with attrition during that time period. In fact, an additional analysis of the sources of turnover from 2011–2012 to 2012–2013 found that voluntary preretirement turnover (including movers and leavers) represented two thirds of the turnover rate during these years (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019), as shown in Figure 2.

Adapted from Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019). Note: percentages do not total 100 due to rounding.

Figure 2. Sources of teacher turnover, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

While attrition due to retirement is predictable and has increased as the teacher workforce ages (Ingersoll et al., 2018), the relatively high preretirement attrition rate is a cause for concern. Attrition rates in the United States compare unfavorably with those in high-performing countries such as Finland, Canada, and Singapore, which typically average leaver rates between 3% and 4% (National Center on Education and the Economy, 2016).

While most research has focused attention on end-of-year teacher turnover, some studies have addressed teacher turnover duringthe school year (Redding & Henry, 2018, 2019). Within-year turnover may be particularly disruptive to student learning, school operations, and staff collaboration and collegiality. An analysis of turnover data in North Carolina showed that an average of 4.64% of teachers turned over during the school year, accounting for one quarter of the total turnover volume (Redding & Henry, 2018). Within-district transfers were more likely to occur within the first 2 months of the school year, while leaving was more likely to occur at the start of the spring semester. Schools with higher numbers of economically disadvantaged and underrepresented minority students had higher rates of both within- and end-of-year turnover, although the relationship between school economic status and turnover was stronger for within-year turnover. Teachers with higher evaluation ratings were also much less likely that those with lower ratings to turn over during the school year. A subsequent analysis showed that within-year turnover had a larger negative impact on student achievement than turnover that occurs at the end of the year (Henry & Redding, in press). Within-year turnover contributes to the workforce churn that is also generated by end-of-year turnover, and constitutes a significant area for further research.

Factors Related to Teacher Turnover

Research has documented a number of factors that are associated with teachers’ decisions to leave or remain in their schools, including certain school and demographic characteristics, level of teaching experience, qualifications, and teaching area. In addition, school contextual factors and teacher working conditions influence teachers’ decisions to remain in their schools. An overview of these factors follows.

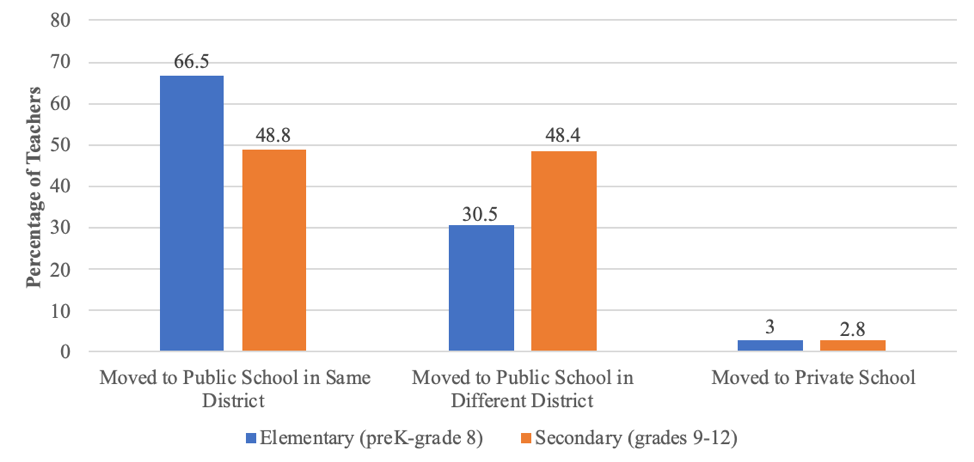

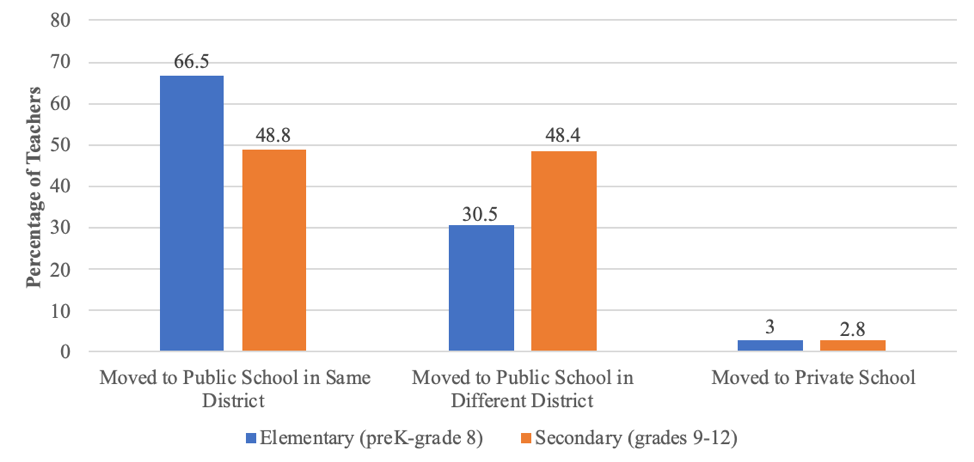

Type of School.Research shows that the movement of teachers out of schools differs by school level and type of school, and is not equally distributed across states, regions, and districts (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Recent national data from 2011–2012 to 2012–2013 show that 8.9% of elementary teachers moved to a different school compared with 7.2% of secondary teachers, but secondary teachers were more likely to leave teaching (8.3%) than elementary teachers (7.1%) (U.S. Department of Education, 2017). Figure 3 depicts the destination of teachers who moved to a different school. Elementary teachers were much more likely to move within-district than outside of the district, while approximately equal rates were seen for secondary teachers. Few elementary or secondary teachers transferred to a private school. While private schools may have advantages such as better working conditions (e.g., smaller class sizes) (Orlin, 2013), they may be less likely to attract public school teachers due to lower salaries and lack of compensation for years of service in teacher retirement systems.

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Education Digest Report (2017).

Figure 3. Percentage of public school teachers who moved to a different school by school level and destination, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

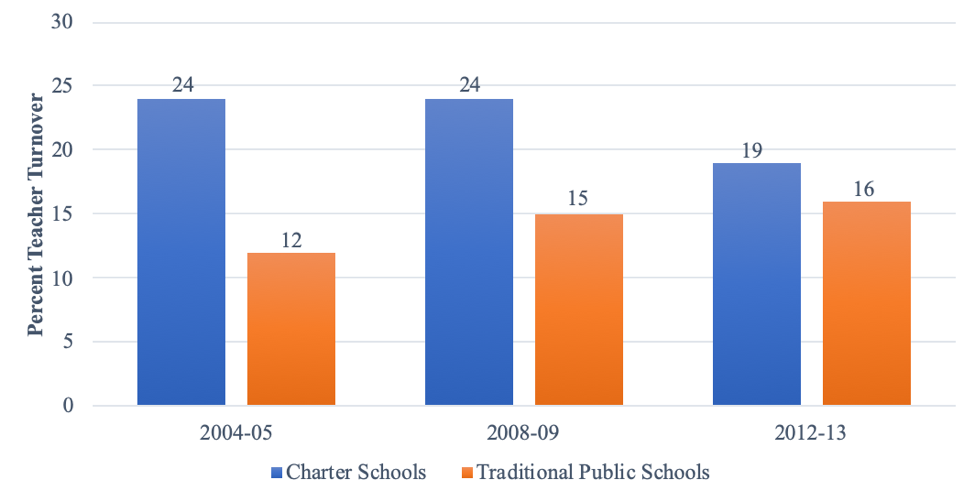

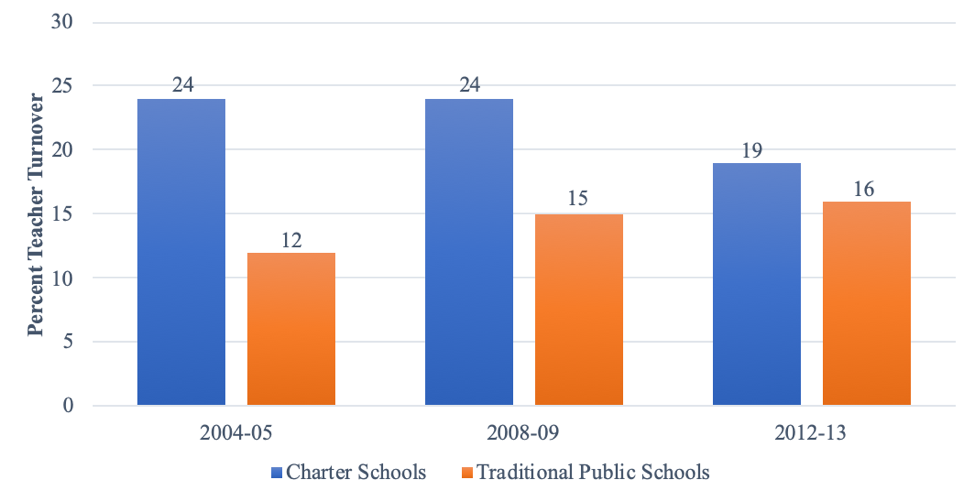

When teacher turnover rates in traditional public schools and charter schools are compared, research consistently shows higher rates of turnover in charter schools (Goldring, et al., 2014; Gross & DeArmond, 2010; Gulosino, Ni, & Rorrer, 2019; Naslund & Ponomariov, 2019; Newton, Rivero, Fuller, & Dauter, 2018; Stuit & Smith, 2012). For example, the Goldring et al. (2014) study found 10.2% mover and 8.2% leaver rates at charter schools compared with 8% mover and 7.7% leaver rates at traditional public schools. Longitudinal trends show a narrowing gap between turnover at the two types of schools, as shown in Figure 4 (Goldring et al., 2014; Stuit & Smith, 2012).

Adapted from Goldring et al., 2014; Stuit and Smith (2012).

Figure 4. Turnover rates at charter schools and traditional public schools, 2004–2005 to 2012–2013

While these trends are encouraging, there is a great degree of variability in turnover in charter schools across various regions and states. For example, Newton and colleagues (2018) found significantly higher turnover rates in Los Angeles charter schools than in traditional public schools, even when controlling for student, teacher, and school characteristics. Specifically, elementary charter school teachers had approximately 35% higher odds of leaving and secondary charter school teachers were close to 4 times more likely to exit their schools than their counterparts in traditional public schools. Naslund and Ponomariov (2019) found that Texas charter school teachers turn over at twice the rate as traditional public school teachers (36.7% versus 18.2%). While the reasons for the higher turnover are unclear (Stuit & Smith, 2012), several explanations have been proposed, including differences in teacher working conditions, preparation, and support, and the fact that greater rates of involuntary turnover tend to occur in charter schools. Roch and Sai (2018) found (using Schools and Staffing Survey data) that teachers in for-profit and nonprofit education management organizations (EMOs) were more likely to report plans to either change schools or leave the profession than those teaching in regular charter schools, with differences partially explained by poorer working conditions, including less administrative support. Some evidence also suggests that new charter school teachers have less access to beginning teacher supports (e.g., seminars or classes) and less supportive communication with administration, and are slightly less likely to report that they were well prepared to handle instructional duties than traditional public school teachers (Bowsher, Sparks, & Hoyer, 2018).

Naslund and Ponomariov’s 2019 study determined negative effects of turnover on student achievement in both charter and traditional public schools, but found the turnover to be slightly less harmful for science and math passing rates in charter schools. The researchers suggested that greater flexibility in hiring and school leaders’ capacity to remove ineffective teachers may alleviate some of the negative student outcomes of turnover in charter schools, but argued for additional research in this area. Understanding the factors influencing the high rates of turnover in charter schools is increasingly important given their substantial growth in recent years, with more than 3 million students now being educated in charter schools nationally (David & Hesla, 2018).

Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) found higher turnover rates in the South, in Title I schools (particularly in math and science, and for alternatively certified teachers), and in schools serving higher proportions of students of color. In fact, teachers in this study left schools with higher proportions of students of color at a rate 46% higher than those teaching the fewest students of color; however, when working conditions are factored in, the predictive relationship between student ethnicity and turnover is reduced. Other research supports these findings, reporting that the rates of turnover have been highest in economically disadvantaged and high-minority urban (Papay et al, 2017) and rural schools (Miller, 2012; Monk, 2007; National Center for Education Statistics, 2017; Sutton, Bausmith, O’Connor, Pae, & Payne, 2014). The rates of mobility (movers) have often reflected an annual disproportionate shuffling from more to less disadvantaged schools, from high- to low-minority schools, and from urban to suburban schools (Ingersoll & May, 2012).

Teacher Characteristics and Qualifications.The exit of teachers from schools is not uniformly spread across different teacher characteristics and qualifications. While women represent the majority of teachers, particularly at the elementary level (Ingersoll et al., 2018), they are also more likely to leave teaching than men due to a variety of factors such as childbearing and better opportunities in other workforce sectors (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014). Younger and older teachers are more likely than middle-aged teachers to turn over, with mobility and attrition generally following a U-shaped pattern as the workforce ages (Allensworth, Ponisciak, & Mazzeo, 2009; Johnson, Berg, & Donaldson, 2005).

Research suggests that beginning teachers have the highest turnover rate of any teacher group (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll, 2003; Papay et al., 2017), with recent national data showing that more than 44% of new teachers exit within 5 years (Ingersoll, Merrill, & Stuckey, 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Raue & Gray, 2015). Papay and colleagues (2017) reported even higher turnover rates in a study on urban schools, with early-career attrition rates ranging from 46% to 71%, depending on the district. Nationally, nearly two thirds of the turnover among beginning teachers occurs within the first 3 years of teaching (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Most of this turnover is voluntary (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017) and includes moving to a different school, leaving teaching temporarily, or leaving the profession permanently. When asked for their reasons for exit, roughly one third of first-year teachers indicated their exit was due to involuntary staffing changes, 40% indicated that family or personal issues were important, 32% left to pursue another job or career, and 44% left due to dissatisfaction with their position (respondents could report more than one reason for their exit) (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Involuntary transfer or dismissal has frequently targeted early-career teachers, with personnel decisions focused on “last in, first out” policies to determine which teachers to discharge (Kraft, 2015). Research shows that teaching effectiveness improves quickly among early-career teachers (Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, Rockoff, & Wyckoff, 2008; Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain, 2005), and, therefore, lower retention rates among these teachers is of particular concern as schools with high turnover often lose a large portion of their talent pipeline.

Working conditions likely explain a large portion of turnover for teachers overall, but may be particularly important factors for beginning teachers, who are adjusting to the profession and their school context (Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Simon & Johnson, 2015). Some evidence suggests that quality mentoring and induction programs can provide supportive structures for new teachers that increase their chances of being retained (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011; Raue & Gray, 2015). Research indicates that many teachers in high-poverty schools do not have mentors, and even those who do have them are less likely to report meaningful interactions about their instruction, partially because their mentors often teach different grades or subjects, or do not teach at the same school (Donaldson & Johnson, 2010).

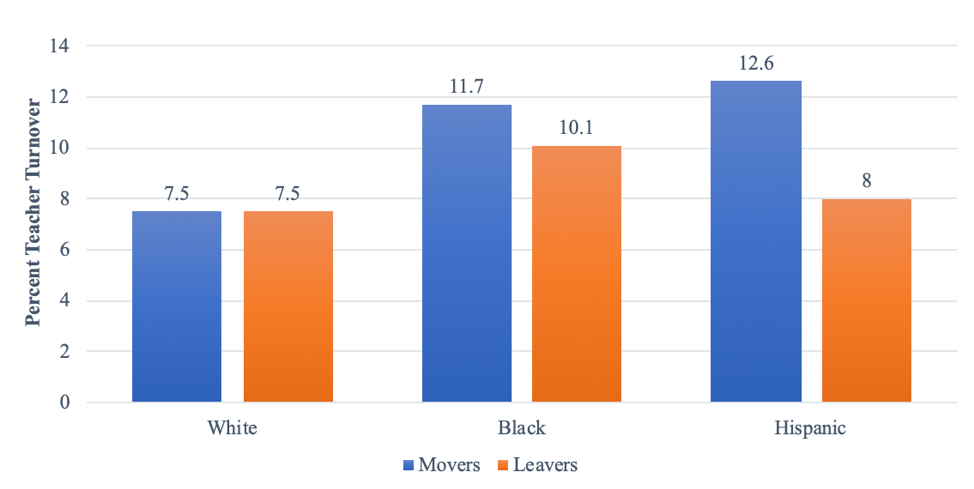

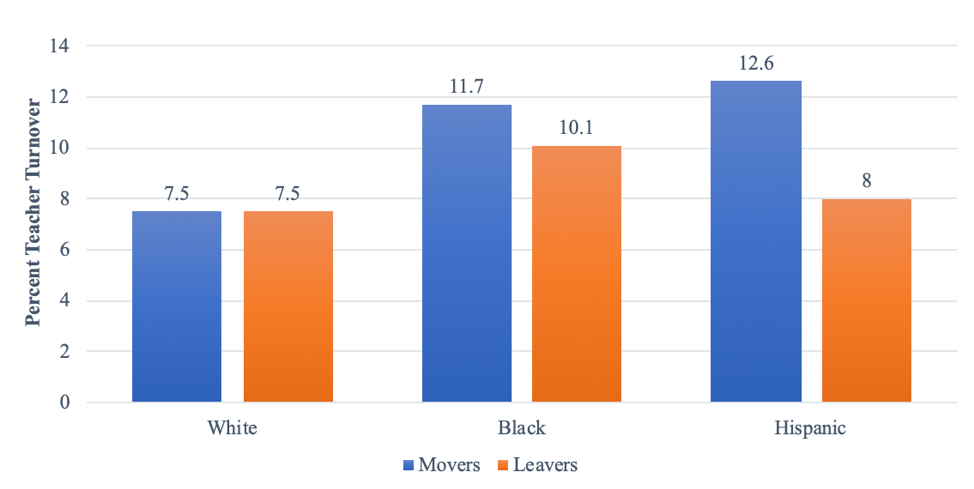

While significantly more teachers of color have entered the workforce in recent years due in part to minority recruitment programs, just 20% of teachers are ethnic minorities compared with more than half of the student population (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Most of the increase in minority teachers has occurred in high-poverty, hard-to-staff schools (Ingersoll & Merrill, 2017); however, the turnover rate among minority teachers has also increased by 45% in recent years (Ingersoll, May, & Collins, 2017) and exceeds that of White teachers in the most recent data available, shown in Figure 5 (Goldring et al., 2014).

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey” (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014). Data are not included for teachers of other ethnicities due to reporting standards not being met because of unacceptably high standard errors.

Figure 5. Percentage of public school teacher movers and leavers by teacher ethnicity, 2012–2013

Studies by Ingersoll and colleagues (2017) and Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) also found larger gaps between teachers of color and White teacher movers than leavers, and the data in both studies suggested that the difficult working conditions in many hard-to-staff schools were responsible for the higher rates of minority teacher turnover. Minority teacher turnover in these schools may be particularly problematic given research that suggests positive academic and behavioral benefits for minority students assigned to teachers of the same ethnicity (Redding, 2019).

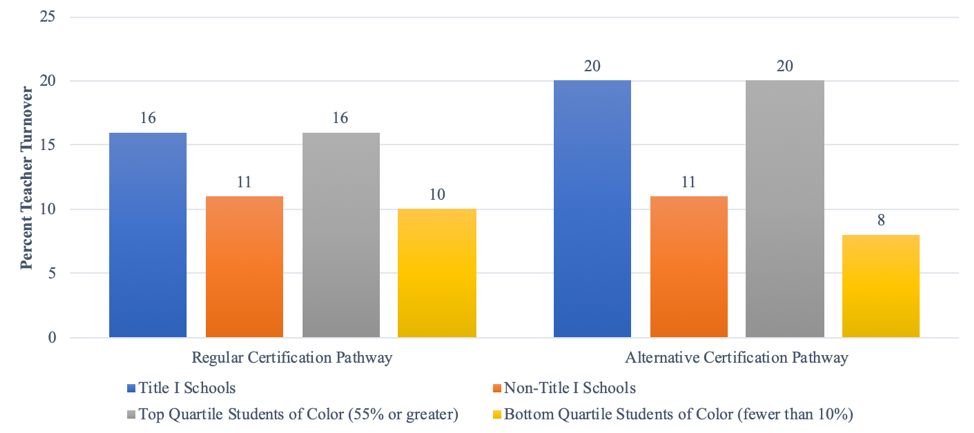

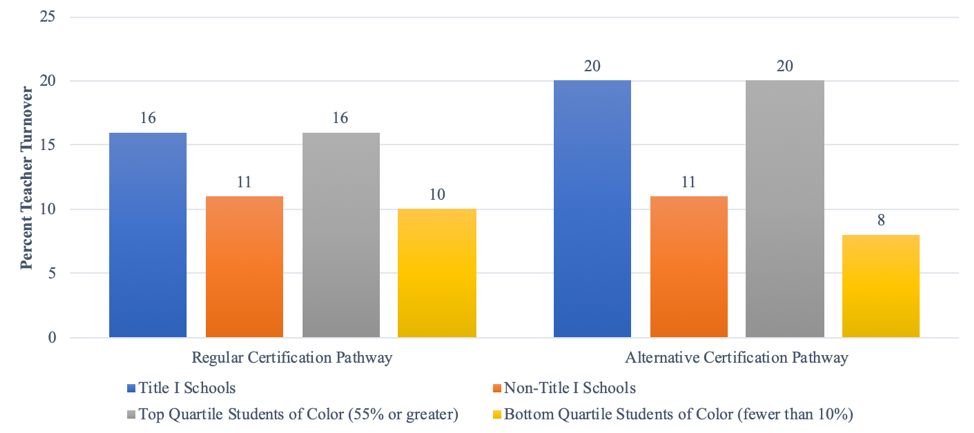

A teacher’s qualifications and entry pathway into the profession also predict the likelihood of turnover. The percentage of teachers entering the profession from outside traditional, in-state university teacher preparation programs nearly doubled from 1999–2000 (13%) to 2011–2012 (25%) (Redding & Smith, 2016), in large part due to staffing shortages in hard-to-staff subjects and schools (Redding & Henry, 2019). Research indicates that, even after controlling for factors that predict high turnover, alternatively certified teachers are still more likely than traditionally prepared teachers to exit the profession (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Boyd et al., 2012; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Redding & Smith, 2016). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) found the turnover rate for alternatively certified teachers 80% higher for Title I than non-Title I schools, and 150% higher in schools with high proportions of students of color (Figure 6). Similar, although less extreme, patterns were observed for regularly certified teachers; however, turnover rate differences among types of schools were statistically significant for both types of certification pathways.

Adapted from Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019)

Figure 6. Teacher turnover by type of school and teacher certification, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

Alternatively certified teachers are more likely to work in urban schools in disadvantaged communities, where working conditions are often less than optimal (Cohen-Vogle & Smith, 2007), with less preparation and support than for traditionally certified teachers (Redding & Smith, 2016). Combining teaching and coursework for certification likely is overwhelming and contributes to the difficult professional situation for these teachers (Redding & Henry, 2019).

Research regarding teacher effectiveness and retention provides evidence of two somewhat contradictory trends. Teachers who have stronger qualifications (e.g., higher certification exam scores or higher undergraduate institution rankings) are more likely to exit the profession (Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2005); however, more effective teachers (as measured by value-added student achievement scores) are less likely to turn over (Goldhaber et al., 2011; Hanushek et al., 2004; Redding & Henry, 2018). While the reasons for these findings are unclear, some researchers have hypothesized that more qualified teachers possess the types of skills that are more highly valued in other professions, but effective teachers stay because their success with students reinforces their professional efficacy and enhances job satisfaction (Katz, 2018).

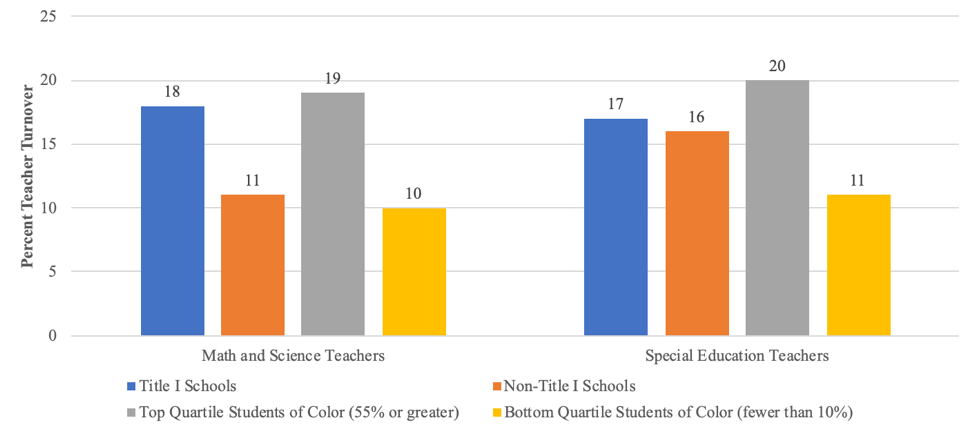

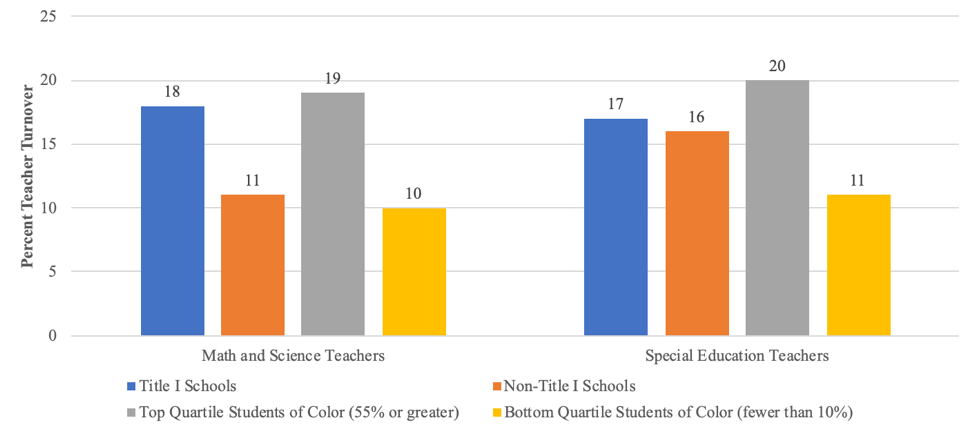

Teaching Area.Results from analyses of teacher attrition and mobility suggest that elementary and humanities teachers have among the lowest turnover rates, and teachers of math, science, special education, and English for foreign language speakers have significantly higher rates (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). Figure 7 demonstrates that math and science teachers are significantly more likely to leave high-minority, high-poverty, and Title I schools than their counterparts teaching math and science in other types of schools (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Ingersoll & May, 2012). Relatively high turnover rates among math and science teachers in high-need schools contribute to shortages in these schools in both urban and rural areas (Goldhaber, Krieg, Theobald, & Brown, 2015; Player, 2015). In addition, as many as 30% of math and science teachers in schools with large numbers of students of color are alternatively certified, compared with just 12% of those in schools with mostly White students (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). This is concerning as many alternative certification pathways lack important coursework and student teaching experiences, which can stymie beginning teachers’ performance and ultimately lead to higher turnover rates (Redding & Henry, 2019).

Adapted from Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond, (2019)

Figure 7. Turnover for math/science and special education teachers, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

Figure 7 shows that while no significant difference in turnover has been found for special education teachers in Title I versus non-Title I schools, rates are considerably higher in high-minority compared with low-minority schools (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Special education teachers overall have higher average turnover rates than general education teachers, particularly during the early career years (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Vittek, 2015). These teachers are likely to face difficult working conditions, such as excessive paperwork, lack of collaboration with colleagues, lack of appropriate induction/mentoring, and lack of administrative support, all of which increase the likelihood that they will transfer to a general education position or leave teaching entirely (Boe, Cook, & Sunderland, 2008; McLesky, Tyler, & Flippin, 2004; Vittek, 2015). Recent research by Gilmour and Wehby (in press) has also found that as the proportion of students with disabilities increases in the classrooms of general education teachers, the likelihood of turnover increases (but not for special education teachers); however, teaching students with emotional/behavioral disabilities is related to increased turnover rates for both special education and general education teachers. Special education teacher turnover rates along with insufficient numbers of newcomers being prepared has led to teacher shortages in this field, and currently teacher shortages in special education represent the largest shortages in 48 of the 50 states (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016).

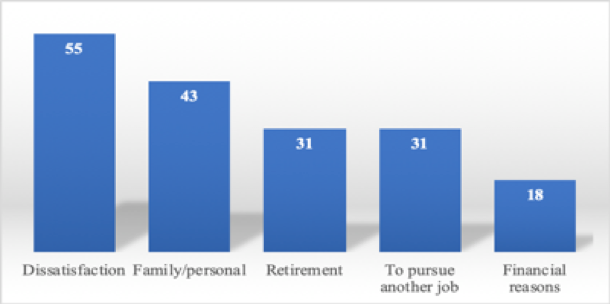

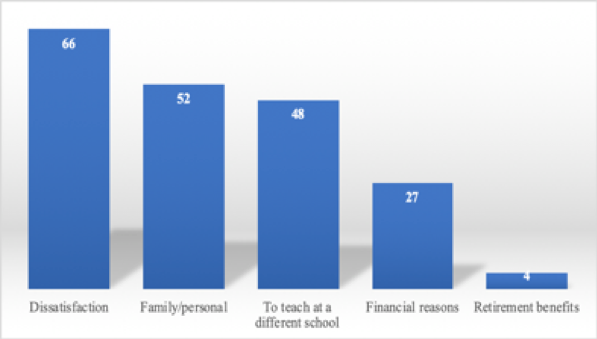

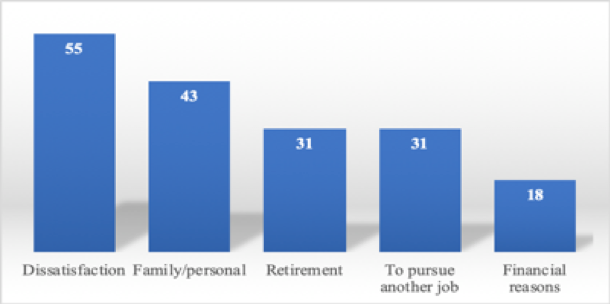

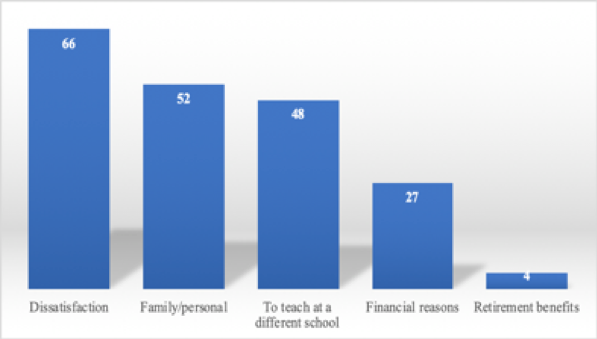

Teacher-Reported Reasons for Turnover.Understanding the reasons teachers leave may help educators develop solutions to address teacher concerns and reduce turnover. Recent data illustrate the factors that teachers report as very important in their decision to leave the teaching profession (Figure 8) or to move to a different school (Figure 9) (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017).

Adapted from Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond (2017). Figure displays percentages of teachers reporting each factor as important; teachers were able to select more than one reason, so percentages do not total 100.

Figure 8. Factors important in teachers leaving the profession

Adapted from Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond (2017). Figure displays percentages of teachers reporting each factor as important; teachers were able to select more than one reason, so percentages do not total 100.

Figure 9. Factors important in teachers moving to another school

Dissatisfaction was most frequently cited by both movers and leavers as important in their decision to leave. Leavers most frequently cited testing/accountability (25%), problems with administration (21%), and dissatisfaction with teaching as a career (21%) as sources of dissatisfaction; the family/personal reasons they cited included moving to a more conveniently located job, health reasons, and caring for family members. Two thirds of movers reported dissatisfaction as a reason to move, citing concerns with school administration, lack of influence on school decision making, and school conditions such as inadequate facilities and resources (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond’s 2019 research also found that a perceived lack of administrative support and compensation were significantly related to turnover. These findings highlight the importance of working conditions in teacher retention.

Teacher Working Conditions.Working conditions are an important predictor of teacher turnover (e.g., Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Johnson, Kraft, & Papay, 2012), and offer potentially malleable school conditions that can be shaped by changes to educational policy (Katz, 2018). Research has demonstrated that student demographics are important in teachers’ decisions to remain at their schools and that they most often leave schools containing large numbers of low-income, low-achieving, and minority students (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Clotfelter, Ladd, Vigdor, & Wheeler, 2006; Hanushek et al., 2004). However, teacher interviews have revealed that dysfunctional school contexts that make it difficult to succeed with these student populations, rather than the students themselves, are responsible for the decision to leave (Allensworth et al, 2009; Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Johnson et al., 2012). In fact, several studies have demonstrated that teacher working conditions explain most of the relationship between student demographics and teacher turnover (Allensworth et al., 2009; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Ladd, 2011; Simon & Johnson, 2015).

A critical aspect of teacher working conditions that influences retention is the quality of principal leadership (Boyd et al., 2011; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Johnson et al., 2012; Ladd, 2011; Marinell & Coca, 2013). Research suggests that as school leadership improves, the likelihood of teacher turnover decreases (Kraft, Marinell, & Yee, 2016; Ladd, 2011). For example, teachers were more likely to stay at schools where they reported the principal was trusting and supportive of teachers, a knowledgeable instructional leader, an efficient manager, and skilled at forming external partnerships with external organizations (Marinell & Coca, 2013). Additional research indicates that teachers who left schools led by the most effective principals were less likely to be effective than those who left schools led by less successful principals (Branch, Hanushek, & Rivken, 2013). Unfortunately, high-poverty schools are often staffed with less experienced and weaker principals (Loeb, Kalogrides, & Horng, 2010); on a positive note, research has also shown that an effective principal may offset teacher turnover in disadvantaged schools (Grissom, 2011; Kraft et al., 2016).

Teachers are more likely to remain in schools when they report satisfaction with school facilities and resources (e.g., textbooks or technology tools) (Loeb, Darling-Hammond, & Luczak, 2005). Turnover is also more frequent in schools with poor student discipline and where there are issues with teacher safety (Allensworth et al., 2009; Boyd et al., 2005; Grissom, 2011; Ingersoll, 2001). Additional teacher working conditions that have been identified as important to teacher retention (and that are related to administrative leadership) include a sense of collective responsibility for student outcomes, a sense of collegiality and trusting working relationships, parent-teacher interaction, time for collaboration and planning, and expanded roles for teachers (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Kraft et al., 2016; Simon & Johnson, 2015). Simon and Johnson cited three factors supporting teachers’ work with their colleagues: (1) an inclusive environment of respect and trust (e.g., teachers respect one another and trust that their colleagues are “doing the right thing for the right reasons”); (2) formal structures for collaboration and support (e.g., well-designed induction/mentoring programs and well-designed instructional teams or professional learning communities, or PLCs); and (3) a shared set of professional goals and purposes (e.g., all teachers share a social justice perspective and are motivated to help disadvantaged students achieve).

The research literature also suggests that professional empowerment and opportunities for autonomy and shared decision making are important (Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll, 2003; Ingersoll & May, 2012; Marinell & Coca, 2013; Wronowski, 2018). Goldring et al. (2014) found that of teachers who left the profession, more than half indicated they had more autonomy in their work and greater influence over workplace practices and policies in their current job than they did as teachers. Inadequate autonomy and empowerment may be particularly important for minority teachers teaching in hard-to-staff schools as well as responsible for many of these teachers leaving the profession and subsequent teacher shortages (Ingersoll & May, 2012; Ingersoll et al., 2017). In addition, research has ascribed higher teacher attrition to a perceived lack of influence and autonomy in the school, and few opportunities for career advancement and career pathways (Ingersoll & Perda, 2010; TNTP, 2012), suggesting that leadership opportunities may encourage many teachers to stay. A recent study found that two thirds of national and state “teacher of the year” award winners rated teacher leadership opportunities as a top growth experience that contributed positively to their career progression (Behrstock-Sherratt, Bassett, Olson, & Jacques, 2014).

A related aspect of teacher working conditions that influences retention is the level of compensation. Teacher salaries are generally not competitive with other labor markets (Hanushek, Piopiunik, & Wiederhold, 2014), even when controlling for the shorter work year, with new teachers earning approximately 18% less than individuals working in other fields, and midcareer teachers earning 30% less (Baker, Sciarra, & Farrie, 2015, 2018). Research consistently shows that teachers who work in districts that pay less are more likely to leave their jobs (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Goldring et al., 2014; Podolsky, Kini, Bishop, & Darling-Hammond, 2016). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) found a significant relationship between the highest teacher salary possible in a district and turnover; for example, teachers who could earn more than $78,000 in their districts had an attrition rate 31% lower than those who could earn a maximum of only $60,000. Gray and Taie (2015) found a 10-point percentage gap in turnover rates between novice teachers whose first-year salary was $40,000 or higher compared with beginning teachers earning less. Whether math and science and other in-demand teachers decide to remain in teaching is particularly dependent on salary (Adamson & Darling-Hammond, 2011). When teachers were asked what would bring them back to the profession, financial considerations including salary increases and an ability to maintain teaching retirement benefits ranked high (Podolsky et al, 2016).

Research further indicates that the highest paid teachers in high-poverty schools are paid significantly less than the highest paid teachers in less disadvantaged communities (Adamson & Darling-Hammond, 2011). The inability to adequately reward excellent teachers contributes to an inequitable distribution of high-quality teachers among schools within districts, as teachers with more seniority transfer out of less desirable placements and are replaced by less experienced and often less effective teachers (Podgursky & Springer, 2011). Many educational researchers and policymakers are advocating for reforms to the compensation teachers receive, particularly in hard-to-staff subjects and schools (Aragon, 2016; Dee & Goldhaber, 2017; Sutcher et al., 2016).

Summary and Conclusions

Teacher turnover contributes significantly to teacher shortages and often results in the inequitable distribution of effective and qualified teachers across schools. While the overall turnover rate (including teacher movers and leavers) has remained fairly consistent, the rate of preretirement attrition has increased in recent years. Within-year turnover has also been identified in the research as a significant problem, particularly in disadvantaged schools, and negatively impacts student achievement. Elementary school turnover includes a greater proportion of movers within districts, while secondary school turnover includes greater percentages of teachers leaving the profession. Teachers in charter schools are more likely to turn over than those teaching in traditional public schools, in many cases due to poorer working conditions. Teacher turnover is highest among minority teachers (particularly those working in high-need schools), younger or older teachers, those with higher qualifications, beginning teachers, alternatively certified teachers, special education teachers, and teachers of math and science. The key reasons for turnover have centered primarily around dissatisfaction with the job or school due to poor working conditions, which are more predictive of turnover than student demographic characteristics. Principal leadership, teacher relationships and collaboration, a safe school climate, autonomy, shared decision making, and opportunities for leadership and advancement are all important components of teacher working conditions that influence retention. In addition, compensation levels are predictive of turnover, with teachers (particularly those teaching hard-to-staff subjects or students) more likely to exit districts that pay less.

The research cited in this report suggests that teacher turnover is a persistent issue with negative consequences for students and schools but is also linked to several malleable factors that could be addressed through educational policy. In an overview of teacher retention research, Katz (2018) recommended several policy strategies that are consistent with the research reviewed in this report, including focused retention efforts for new teachers, differentiated pay for high-need subject areas and schools, and creating strong cadres of highly effective principals. These strategies and others are discussed in more detail in the Teacher Retention Strategies report.

Citations

Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2012). Funding disparities and the inequitable distribution of teachers: Evaluating sources and solutions. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 20(37), 1–46.

Allensworth, E., Ponisciak, S., & Mazzeo, C. (2009). The schools teachers leave: Teacher mobility in Chicago Public Schools.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. Retrieved from https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/schools-teachers-leave-teacher-mobility-chicago-public-schools

Aragon, S. (2016). Mitigating teacher shortages: Financial incentives. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States. Retrieved from https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Mitigating-Teacher-Shortages-Financial-incentives.pdf

Atteberry, A., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2017). Teacher churning: Reassignment rates and implications for student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,39(1), 3–30.

Baker, B., Sciarra, D. G., & Farrie, D. (2015). Is school funding fair? A national report card.4th ed.Newark, NJ: Education Law Center. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/state_edwatch/Is%20School%20Funding%20Fair%20-%204th%20Edition%20(2).pdf

Baker, B., Sciarra, D. G., & Farrie, D. (2018). Is school funding fair? A national report card. 7th ed.Newark, NJ: Education Law Center. Retrieved from https://edlawcenter.org/assets/files/pdfs/publications/Is_School_Funding_Fair_7th_Editi.pdf

Barnes, G., Crowe, E., & Schaefer, B. (2007). The cost of teacher turnover in five school districts: A pilot study. Washington, DC: National Commission on Teaching and America's Future. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b4ab/6eaa2ac83f4721044e5de193e3e2dec07ac0.pdf

Behrstock-Sherratt, E., Bassett, K., Olson, D., & Jacques, C. (2014).From good to great: Exemplary teachers share perspectives on increasing teacher effectiveness across the career continuum.Washington, DC: Education Policy Center, American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED555657.pdf

Boe, E., Cook, L. H., & Sunderland, R. J. (2008). Teacher turnover: Examining exit attrition, teaching area transfer, and school migration. Exceptional Child, 75(1), 7–31.

Borman, G. D., & Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 367–409.

Bowsher, A., Sparks, D., & Hoyer, K. M. (2018). Preparation and support for teachers in public schools: Reflections on the first year of teaching (NCES 2018-143). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581881.pdf

Boyd, D., Dunlop, E., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Mahler, P., O’Brien, R. O., & Wyckoff, J. (2012). Alternative certification in the long run: A decade of evidence on the effects of alternative certification in New York City. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Education Finance and Policy Conference, Boston, MA.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2011). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 303–333.

Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Rockoff, J., & Wyckoff, J. (2008). The narrowing gap in New York City teacher qualifications and its implications for student achievement in high-poverty schools. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27(4), 793–818.

Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2005). Explaining the short careers of high-achieving teachers in schools with low-performing students.American Economic Review, 95(2), 166–171.

Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2013). School leaders matter: Measuring the impact of effective principals. Education Next, 13(1), 62–69.

Bryk A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT.pdf

Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(36), 1–32.

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2006). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85, 1345–1379.

Cohen-Vogel, L., Smith, T. M. (2007). Qualifications and assignments of alternatively certified teachers: Testing core assumptions. American Educational Research Journal, 44(3), 732–753.

David, R., & Hesla, K. (2018). Estimated public charter school enrollment, 2017–2018. Washington, D.C.: National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Retrieved from https://www.publiccharters.org/sites/default/files/documents/2018-03/FINAL%20Estimated%20Public%20Charter%20School%20Enrollment%252c%202017-18_0.pdf

Dee, T. S., & Goldhaber, D. (2017). Understanding and addressing teacher shortages in the United States.The Hamilton Project. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/es_20170426_understanding_and_addressing_teacher_shortages_in_us_pp_dee_goldhaber.pdf

Donaldson, M. L., & Johnson, S. M. (2010). The price of misassignment: The role of teaching assignments in Teach for America teachers’ exit from low-income schools and the teaching profession. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 299–323.

Gilmour, A. F., & Wehby, J. J. (in press). The association between teaching students with disabilities and teacher turnover. Journal of Educational Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Allison_Gilmour/publication/333675165_The_Association_Between_Teaching_Students_with_Disabilities_and_Teacher_Turnover/links/5cfe5251299bf13a384a7997/The-Association-Between-Teaching-Students-with-Disabilities-and-Teacher-Turnover.pdf

Goldhaber, D., Gross, B., & Player, D. (2011). Teacher career paths, teacher quality, and persistence in the classroom: Are public schools keeping their best? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30(1), 57–87.

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Theobald, R., & Brown, N. (2015). Refueling the STEM and special education teacher pipelines. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(4), 56–62.

Goldhaber, D., Lavery, L., & Theobald, R. (2015). Uneven playing field? Assessing the teacher quality gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students. Educational Researcher, 44(5), 293–307.

Goldring, R., Taie, S., & Riddles, M. (2014). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey (NCES 2014-077). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014077.pdf

Gray, L., & Taie, S. (2015). Public school teacher attrition and mobility in the first five years: Results from the first through fifth waves of the 2007-08 beginning teacher longitudinal study (NCES 2015-337). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015337.pdf

Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552–2585.

Gross, B., & DeArmond, M. (2010). Parallel patterns: Teacher attrition in charter vs. district schools. Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education, University of Washington. Retrieved from http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/pub_ics_Attrition_Sep10_0.pdf

Gulosino, C., Ni, Y., & Rorrer, A. K. (2019). Newly hired teacher mobility in charter schools and traditional public schools: An application of segmented labor market theory. American Journal of Education, 125(4), 547–592.

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J., & Rivkin, S. (2004). Why public schools lose teachers. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 326–354.

Hanushek, E. A., Piopiunik, M., & Wiederhold, S. (2014). The value of smarter teachers: International evidence on teacher cognitive skills and student performance. Working Paper No. 20727. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w20727.pdf

Henry, G. T., & Redding, C. (in press). The consequences of leaving school early: The effects of within-year and end-of-year teacher turnover. Education Finance and Policy.Retrieved from https://cdn.theconversation.com/static_files/files/269/withinyear_efp_final.pdf?1536242239

Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534.

Ingersoll, R. (2003). Is there really a teacher shortage? Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Ingersoll, R. M., & May, H. (2012). The magnitude, destinations, and determinants of mathematics and science teacher turnover. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(4), 435–464.

Ingersoll, R., May, H., & Collins, G. (2017). Minority teacher recruitment, employment, and retention: 1987 to 2013. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Minority_Teacher_Recruitment_REPORT.pdf

Ingersoll, R., & Merrill, E. (2017). A quarter century of changes in the elementary and secondary teaching force: From 1987 to 2012 (NCES 2017-092). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, L., & Stuckey, D. (2014). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated April 2014. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from http://www.cpre.org/sites/default/files/workingpapers/1506_7trendsapril2014.pdf

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated October 2018. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=cpre_researchreports

Ingersoll, R., & Perda, D. A. (2010). Is the supply of mathematics and science teachers sufficient? American Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 563–594.

Ingersoll, R., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233.

Johnson, S. M., Berg, J. H., & Donaldson, M. L. (2005). Who stays in teaching and why: A review of the literature on teacher retention. The Project on the Next Generation of Teachers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from https://projectngt.gse.harvard.edu/files/gse-projectngt/files/harvard_report.pdf

Johnson, S. M., & Birkeland, S. E. (2003). Pursuing a “sense of success”: New teachers explain their career decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 581–617.

Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), p. 1–39.

Katz, V. (2018). Teacher retention: Evidence to inform policy. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia. Retrieved from https://curry.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/epw/Teacher%20Retention%20Policy%20Brief.pdf

Kraft, M. A. (2015). Teacher layoffs, teacher quality, and student achievement: Evidence from a discretionary layoff policy. Education Finance and Policy, 10(4), 467–507.

Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Yee, D. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal,53(5), 1411–1449.

Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235–261.

Loeb, S., Darling-Hammond, L., & Luczak, J. (2005). How teaching conditions predict teacher turnover in California schools. Peabody Journal of Education, 80(3), 44–70.

Loeb, S., Kalogrides, D., & Horng, E. L. (2010). Principal preferences and the uneven distribution of principals across schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 205–229.

Marinell, W. H., & Coca, V. M. (2013). Who stays and who leaves? Findings from a three-partstudy of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools. New York, NY: Research Alliance for New York City Schools. Retrieved from https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/media/users/sg158/PDFs/ttp_synthesis/TTPSynthesis_Report_March2013.pdf

McLeskey, J., Tyler, N. C., & Flippin, S. S. (2004). The supply of and demand for special education teachers: A review of research regarding the chronic shortage of special education teachers. Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 5–21.

Miller, L. C. (2012). Working paper: Understanding rural teacher retention and the role of community amenities. Charlottesville, VA: Center on Education Policy and Workforce Competitiveness.

Monk, D. H. (2007). Recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers in rural areas. Future of Children, 17(1), 155–174.

Naslund, K., & Ponomariov, B. (2019). Do charter schools alleviate the negative effect of teacher turnover? Management in Education, 33(1), 11–20.

National Center on Education and the Economy. (2016). Empowered educators: How high-performing systems shape teaching quality around the world. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://ncee.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/RecruitmentPolicyBrief.pdf

Newton, X., Rivero, R., Fuller, B., & Dauter, L. (2018). Teacher turnover in organizational context: Staffing stability in Los Angeles charter, magnet, and regular public schools. Teachers College Record, 120(3), 1–36.

Orlin, B. (2013, October 24). Why are private-school teachers paid less than public-school teachers? The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/10/why-are-private-school-teachers-paid-less-than-public-school-teachers/280829/

Papay, J. P., Bacher-Hicks, A., Page, L. A., & Marinell, W. H. (2017). The challenge of teacher retention in urban schools: Evidence in variation from a cross-site analysis. Educational Researcher, 46(8), 434–448.

Player, D. (2015). The supply and demand for rural teachers. Rural Opportunities Consortium of Idaho. Retrieved from http://www.rociidaho.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ROCI_2015_RuralTeachers_FINAL.pdf

Podgursky, M., & Springer, M. (2011). Teacher compensation systems in the United States K–12 public school system. National Tax Journal, 64(1), 165–192.

Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators.Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Solving_Teacher_Shortage_Attract_Retain_Educators_REPORT.pdf

Raue, K., & Gray, L. (2015). Career paths of beginning school teachers: Results for the first through fifth waves of the 2007–08 Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study.Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015196.pdf

Redding, C. (2019). A teacher like me: A review of the effect of student-teacher racial/ethnic matching on teacher perceptions of students and student academic and behavioral outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 499–535.

Redding, C., & Henry, G. T. (2018). New evidence on the frequency of teacher turnover: Accounting for within-year turnover. Educational Researcher, 47(9), 577–593.

Redding, C., & Henry, G. T. (2019). Leaving school early: An examination of novice teachers’ within- and end-of-year turnover. American Educational Research Journal, 56(1), 204–236.

Redding, C., & Smith, T. M. (2016). Easy in, easy out: Are alternatively certified teachers turning over at increased rates? American Educational Research Journal, 53(4), 1086–1125.

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417–458.

Roch, C. H., & Sai, N. (2018). Stay or go? Turnover in CMO, EMO and regular charter schools. Social Science Journal, 55(3), 232–244.

Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36.

Simon, N. S., & Johnson, S. M. (2015). Teacher turnover in high-poverty schools: What we know and can do. Teachers College Record, 117(3), 1–36.

Sorensen, L. C., & Ladd, H. F. (2018). The hidden costs of teacher turnover. Working Paper No. 203-0918-1. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from https://caldercenter.org/publications/hidden-costs-teacher-turnover

Stuit, D.A, & Smith, T.M. (2012). Explaining the gap in charter and traditional public school teacher turnover rates. Economics of Education Review, 31(2), 268–279.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/A_Coming_Crisis_in_Teaching_REPORT.pdf

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2019). Understanding teacher shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(35), 1–39.

Sutton, J. P., Bausmith, S. C., O’Connor, D. M., Pae, H. A., & Payne, J. R. (2014). Building special education teacher capacity in rural schools: Impact of a Grow Your Own program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 33(4), 14–23. Retrieved from http://www.sccreate.org/Research/article.CREATE.RSEQ.14.pdf

Synar, E., & Maiden, J. (2012). A comprehensive model for estimating the impact of teacher turnover. Journal of Education Finance, 38, 130–144.

TNTP. (2012). The irreplaceables: Understanding the real retention crisis in America’s urban schools.New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_Irreplaceables_2012.pdf

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Digest of Education Statistics.Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_210.30.asp

Vittek, J. E. (2015). Promoting special educator teacher retention: A critical review of the literature. SAGE Open, (5)2, 1–6.

Wronowski, M. L. (2018). Filling the void: A grounded theory approach to addressing teacher recruitment and retention in urban schools. Education and Urban Society, 50(6), 548–574.