Fidelity of Implementation in Educational Research and Practice

Fidelity of Implementation PDF

Gage, N., MacSuga-Gage, A., and Detrich, R. (2020). Fidelity of Implementation in Educational Research and Practice. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/systems-program-fidelity

The effectiveness of implementing a new system, practice, or intervention is contingent on executing it as prescribed. This is true for all change efforts including those in education (Bruhn, Hirsch, & Lloyd, 2015; Keller-Margulis, 2012). If a new initiative, from whole-school systems change to an individualized intervention, is not implemented as designed, the likelihood of a positive outcome—whether school turnaround, increased reading achievement, or decreased problem behavior—is minimal at best. Perhaps the best analogy is from the medical field. A patient is diagnosed with strep throat and his or her doctor prescribes an antibiotic. The instructions inform the patient to take one pill twice daily for 10 days. The patient takes both doses of antibiotic on the first day, but only one on the second and third days. Remembering again, the patient takes two doses on the fourth and fifth days, but then stops taking the antibiotic. By the end of 10 days, the patient returns to the doctor, complaining that the medicine did not work. Upon review, the doctor discovers that the patient only took 8 of the 20 prescribed antibiotic pills, or, put differently, the patient implemented the intervention with 40% fidelity. The reason for the patient’s lack of improvement was not that the intervention failed but that it was not implemented as prescribed.

The terms “fidelity” and “integrity” are used synonymously throughout the literature of many fields including education; this overview uses the former term but acknowledges that the definitions are equivalent. We also want to differentiate our focus here from the expanding area of implementation research and science (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). Implementation research has been defined as (1) the systematic inquiry into innovations enacted in controlled settings or in ordinary practice, (2) the factors that influence innovation enactment, and (3) the relationships between innovations, influential factors, and outcomes (Century & Cassata, 2016). Implementation science has been defined as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice” (Eccles & Mittman, 2006, p. 1). Fidelity of implementation is a critical component of all stages of implementation research and science (e.g., a primary consideration of contextual fit is the capacity to implement with fidelity), but this overview focuses specifically on fidelity of implementation of new systems, practices, and interventions in educational settings.

The construct “implementation fidelity” has been conceptualized in a variety of ways (Nilsen, 2015). For example, Sanetti and Kratochwill (2009) identified six different conceptual models for fidelity. These embraced different domains and indicators of fidelity, including adherence to a protocol (i.e., completing all necessary steps/parts of an intervention), quality of the implementation, and quantity or dosage of the intervention. The key domains and indicators are described in more detail below, but the takeaway is that fidelity is multidimensional and includes myriad domains and measurable indicators.

Our purpose is to disentangle and clarify what fidelity of implementation is and isn’t, and to provide both empirical (i.e., based on data and experience) and conceptual (i.e., based on theory and logic) evidence that will help researchers and practitioners understand the importance of fidelity. Below, we define fidelity of implementation, review the importance and use of fidelity of implementation in educational research and practice, describe measurement approaches and issues, and provide actionable guidance for researchers and practitioners to consider.

Background and History

Concerns about fidelity of implementation and the need to measure and report on it are not new. In 1974, Berman and McLaughlin reviewed the literature on implementation of new education practices and reforms. The authors found minimal impact on student outcomes, which they argued was due in part to the new practices “not being properly implemented” (p. 1). More succinctly, they noted, “although the outcomes may be disappointing, they do not accurately reflect the potential of innovative ideas because many innovations are not implemented according to plan” (p. 11). The authors went on to advance a conceptual model to increase implementation fidelity and student outcomes based on three stages of change: (1) support (professional development), (2) implementation, and (3) incorporation (integrating the new practice into regular practice). As part of the model, the authors explicitly noted that both the definitions of project activities and the implementation of those activities had a direct effect on incorporation of the project into typical practice and on student outcomes. Although the authors highlighted the importance of fidelity, they did not describe approaches for measuring the presence or absence of implementation components.

In 1982, Peterson, Homer, and Wonderlich were among the first researchers in education to highlight the importance of measuring fidelity. They were concerned that failure to measure fidelity, or how well the intervention was implemented, would make it difficult to judge the effectiveness of the intervention. In essence, their point was that conclusions about the effectiveness of an independent variable (i.e., the variable that is controlled or changed in an experiment), whether the implementation of a schoolwide model such as response-to-intervention (Keller-Margulis, 2012) or a classroom management practice, such as behavior specific praise (Ennis, Royer, Lane, & Dunlap, 2018), must be made in the context of the fidelity of implementation of that intervention.

A recent study on the Good Behavior Game, a classwide behavior management intervention, highlights this concern. Joslyn and Volmer (2020) conducted a multiple baseline study with three teachers trained to implement the Good Behavior Game. Following training and implementation of the game, disruptive behavior in all three classrooms clearly decreased. However, the authors found that the teachers implemented the intervention with 50% or less fidelity, raising the question of whether or not the intervention caused the change in student behavior, or if simply doing something new, even poorly, was enough to change student behavior. There are no established criteria for how much fidelity is necessary for an intervention to be effective. Further, it is unlikely that a universally accepted criteria could be developed as the amount of fidelity necessary may be different for each intervention.

The focus of Peterson et al. (1982) as well as others (e.g., Gresham, 1989) was only on procedural fidelity, or adherence, meaning implementing as prescribed (see below). Moncher and Prinz (1991) expanded fidelity beyond adherence to include treatment differentiation (Kazdin, 1986). Differentiation is the degree to which two or more interventions differ theoretically and procedurally. As a component of fidelity of implementation, differentiation is important in comparing interventions. Interpreting the efficacy of one approach is confounded if the comparison approach is similar, and explicit differences between the two approaches are not clearly articulated. For example, if a study compared implementation of Schoolwide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS), described below, with Safe and Civil Schools (Ward & Gersten, 2013), a proprietary version of SWPBIS, but did not articulate explicitly how implementation was different, any interpretation of effect would be suspect. Moncher and Prinz (1991) noted that researchers should develop operationally defined treatment definitions, implementer training protocols, treatment manuals, and supervision of treatment agents. In their review, which focused on clinical psychiatry and marital therapy, the authors identified 359 research studies published between 1980 and 1988. Of those, only 32% used a treatment manual, only 21% supervised implementers, and only 18% conducted adherence checks.

Dane and Schneider (1998), building from prior conceptualizations (e.g., Blackely et al., 1987; Moncher & Prinz, 1991; Peterson et al., 1982), expanded the definition of fidelity. They conducted a systematic review of fidelity in prevention research, operationally defined five types of fidelity (adherence, exposure, quality of delivery, responsiveness, and differentiation) and reviewed studies for the presence of each. They defined each type of fidelity as follows:

- Adherence is the extent to which program components were delivered as prescribed.

- Exposure (called dosage in this overview) is an index of the number of sessions implemented; the length of each session; and/or the frequency of components implemented.

- Quality is the qualitative aspects of program delivery, such as implementer enthusiasm, preparedness, perceptions of effectiveness, and attitudes toward the program.

- Responsiveness is participant response to program sessions, including levels of participation and enthusiasm.

- Differentiation is assurance that participants in each experimental condition (e.g., treatment compared with control condition; baseline compared with intervention phase) received only the planned activities.

Unlike prior reviews, Dane and Schnieder’s included quality as a component of fidelity. Quality is important, particularly in education, where the “how” of implementation can have a meaningful impact on the outcome. For example, Unlu and colleagues (2017) evaluated the relationship between fidelity of implementation of Breakthrough to Literacy, an early literacy intervention, and young children’s literacy skills. The authors collected a series of fidelity indicators, including the Quality of Instruction in Language and Literacy (QUILL), a Likert scale observation of the quality of a teacher’s literacy instruction. (A Likert scale is a common tool used to measure attitudes or perceptions, typically including a range of responses from strongly agree to strongly disagree.) The observers rated teachers on how well they implemented specific components of literacy instruction, including activities to promote letter/word knowledge and understanding of sounds. Although quality of implementation is important, it is not regularly measured. Of the 162 studies reviewed by Dane and Schneider (1998), only 39 collected and reported any fidelity data and only one collected quality of implementation[C8] .

Perhaps no event in education has impacted interest in fidelity as much as the advent of the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES), which was established with the passage Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002 and is the department’s statistics and research arm. As part of IES’s mission, new funding streams were established for producing innovative educational research, but reviewed and evaluated against more rigorous standards than previously required (Hedges, 2018). One of the critical features of all IES research grants is the requirement that fidelity be measured. Any intervention developed with IES funding must include a direct measure of fidelity, ensuring that the intervention was implemented as designed. IES has also invested directly in fidelity research. For example, in 2010, IES funded Project PRIME: Planning Realistic Intervention Implementation and Maintenance by Educators, led by Sane ti and Kratochwill, focused on methods to increase knowledge about fidelity and fidelity approaches and use by practitioners. The work of IES has increased interest in and assessment of fidelity of implementation in research, but there is little evidence of any impact on practice.

[A head]Elements of Implementation Fidelity

Sanetti and Kratochwill (2009) synthesized six conceptual definitions of fidelity of implementation and condensed 19 different components into four broad categories: (1) content, (2) quality (3) quantity, and (4) process. Each of the four categories are not operationally defined but instead work to tie together 19 operationally defined components. Recently, van Dijk, Gage, and Lane (2020) took a practical approach to defining the key features of fidelity of implementation, borrowing, in particular, from Dane and Schneider’s (1998) five dimensions of fidelity. This overview relies on Dijk et al.’s definitions of the five dimensions:

- Adherence. Measures of adherence indicate the degree to which all elements of an intervention were implemented. Measures of adherence are reported as either the percentage of steps executed or a value judgment based on a measure. For example, teachers are trained to use behavior specific praise (BSP) to increase prosocial behavior. The intervention is prescribed as six BSP statements, defined as contingent and specific praise statements that tell learners what they did to receive the praise, during large group instruction. Adherence is considered in effect during observation sessions with at least six BSP statements per 15 minutes of instruction.

- Dosage. Measures of dosage indicate some unit of time (e.g., minutes, hours, weeks) or frequency related to the intervention. In many cases, both time and frequency are collected. If a student is to have extra reading support 3 times per week for 30 minutes each time, a. reduced amount of either of these measures will impact a measure of dosage. Measures of time can report on the actual units of time or the difference in time from the recommended amount. It is important to note that dosage may not be a measure of fidelity if there are no recommendations for dosage. However, all interventions should describe a recommended dosage. In the BSP example, dosage is both the total number of BSP statements during the post-training period and the number of observed sessions in which the teachers delivered at least six BSP statements.

- Quality. Measures of quality indicate how well a certain aspect or combination of aspects of the intervention were delivered “not directly related to the implementation of prescribed content” (Dane & Schneider, 1998, p. 45). Quality is measured on a scale with a minimum of three steps (e.g., poor, moderate, excellent quality), with no maximum, and it could be a global rating or an average across multiple elements or multiple observations. For example, a quality measure of BSP delivered by teachers during large group instruction could be measured as a frequency count and be accompanied by a Likert scale for the quality of the BSP statement, with three levels: low, medium, and high. Observers would then make a qualitative judgment about the quality of the BSP, which could include sincerity, specificity, and tone of the teacher.

- Differentiation. Measures of differentiation indicate how the intervention is distinct from another condition. Three scenarios for measures of differentiation should be considered: (1) a measure focused on how the content and/or delivery of the delivery is different from a second intervention; (2) a measure focused on how the content and/or delivery of the intervention is different from a business-as-usual control group; and (3) a measure focused on specific adaptations an intervention provider makes to an intervention protocol to maximize the intervention’s impact on student outcomes. Differentiation for the BSP example would consist of the following: clearly operationally defining the difference between BSP and general praise, as well as differences between BSP and other classroom management strategies (e.g., opportunities to respond, prompting for expectations).

- Responsiveness. Measures of responsiveness indicating how students react to the intervention include (1) engagement, (2) enthusiasm, (3) generalization of skills, and (4) independent use of skills. The BSP example would call for simultaneously collecting students’ on-task and disruptive behavior data, and evaluating whether or not there was a change in student behavior in classrooms using BSP as prescribed.

It is worth noting that not all of these fidelity dimensions must be collected for a practice to be considered implemented with fidelity. There are no empirical standards for prioritizing them, but we suggest that adherence and dosage are the two most important, with adherence as the single most critical dimension. However, research is needed to confirm this position.

As described above, fidelity of implementation in both research and practice has a long history in education (see O’Donnell, 2008, for a more thorough review) and has evolved considerably over the past 40 years. By no means do we consider van Dijk et al.’s (2020) definitions of fidelity as the final word on the subject. The work of Sanetti and Luh (2019) and others (e.g., Massar, McIntosh, & Mercer, 2019) continue to refine and improve both the theoretical and operational frameworks to guide measurement and understanding of fidelity of implementation.

Reviews of Fidelity of Implementation

Although fidelity of implementation has a long history in education, it has also been neglected (Gresham, 2017). A number of authors have attempted to explore how frequently researchers have collected and reported on fidelity and the relationship between fidelity and outcomes (responsiveness). A number of these reviews have been conducted outside education. For example, in reviewing 63 studies of social work interventions, Naleppa and Cagle (2010) found that only 29% collected fidelity data. Moncher and Prinz (1991) identified 359 psychosocial treatment studies published between 1980 and 1988, and found that only 45% of the studies reported an indicator of fidelity. Durlak and DuPre (2008) reviewed data from 542 intervention studies across a variety of fields and, although not reporting on frequency of fidelity, found that implementation fidelity was statistically significantly and positively associated with intervention outcomes.

A number of reviews of fidelity of implementation have been published in education. For example, O’Donnell (2008) reviewed K–12 core curriculum studies and coded them for indicators of fidelity of implementation. The author identified 23 studies that described fidelity, but only five (22%) included a quantitative measure of fidelity and examined the relationship between fidelity and student outcomes (Allinder, Bolling, Oats, & Gagnon, 2000; Hall & Loucks, 1977; Penuel & Means, 2004; Songer & Gotwals, 2005; Ysseldyke et al., 2003). Quantitative measures of fidelity are important as they provide a comparable scale for interpreting results. For example, a study may report that five of eight intervention steps were completed, or 63% fidelity. This percentage can then be compared to recommended levels or across different implementations or studies.

In the five studies that reported quantitative fidelity data and examined the association with student outcomes, higher fidelity was consistently related to higher student outcomes. Van Dijk and colleagues (2020) identified 50 reading intervention studies that included fidelity of implementation data as part of the analysis of student outcomes. They examined how fidelity was reported; 64% reported data on dosage of the independent variable, 36% reported a combined measure of adherence and quality, and 26% reported only adherence. Unlike prior studies, these didn’t show a clear relationship between fidelity and student outcomes. Only 32% of studies that reported data on dosage found a significant relationship between fidelity and student outcomes; 41% of the studies that reported data on adherence and quality found a significant relationship; and only 24% of the studies that reported data on adherence found a significant relationship.

Systematic Review of Educational Intervention Reviews to Measure How Often Fidelity Is Reported

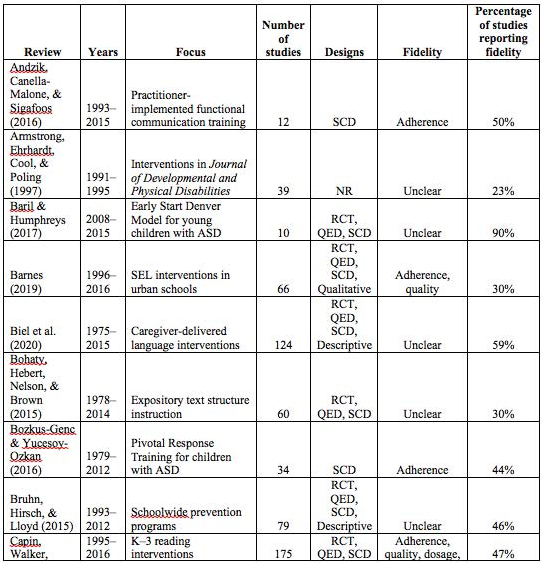

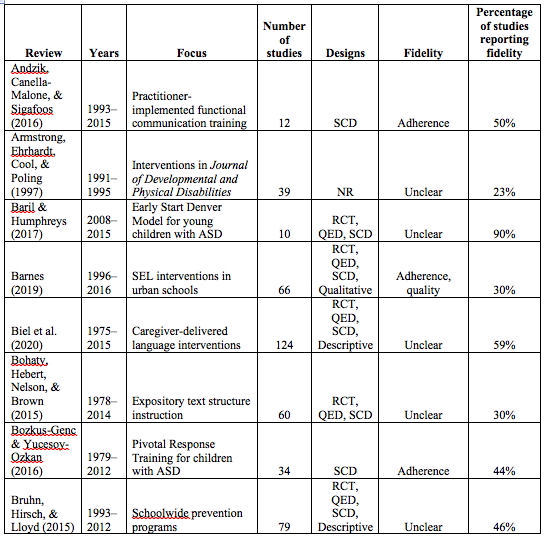

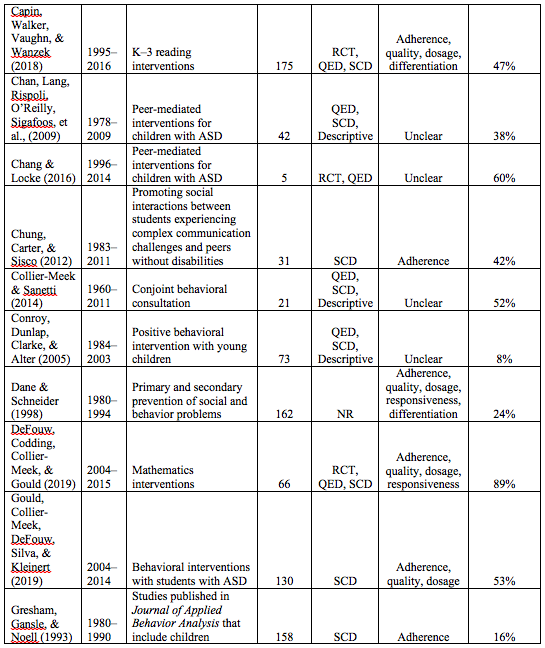

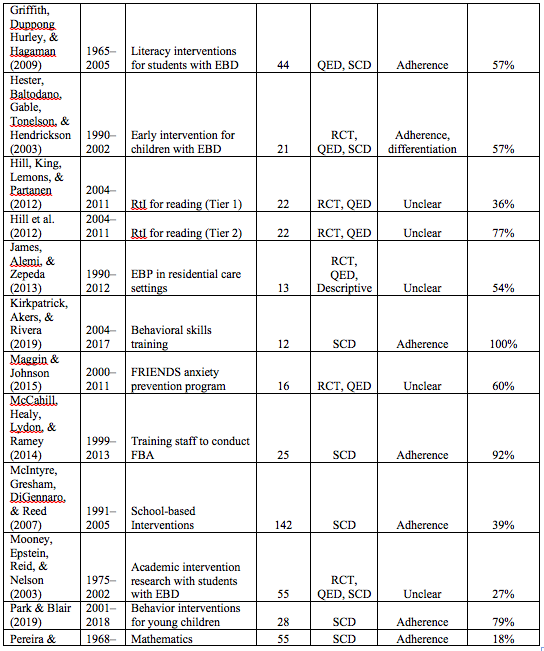

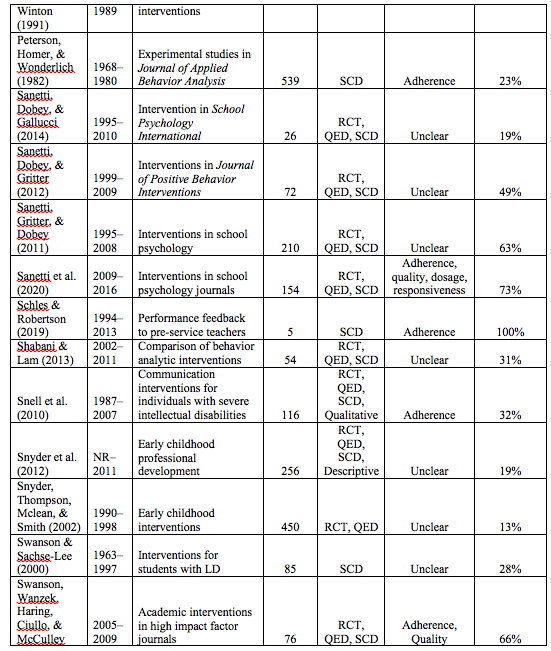

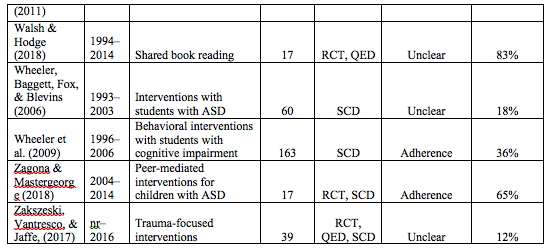

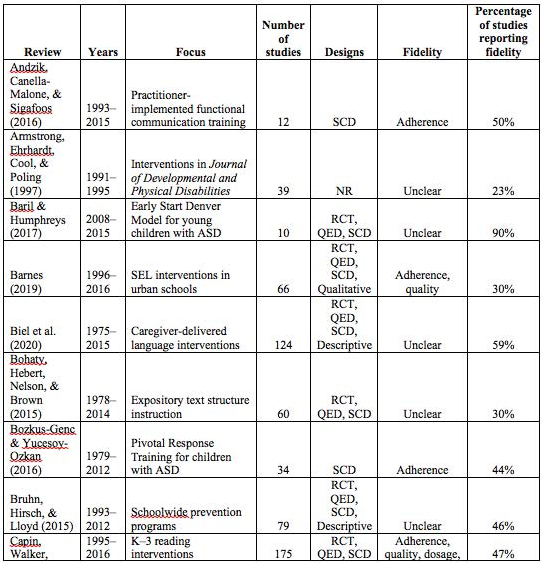

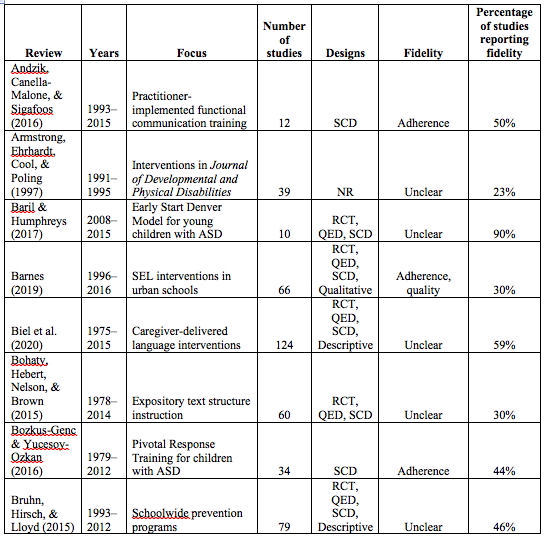

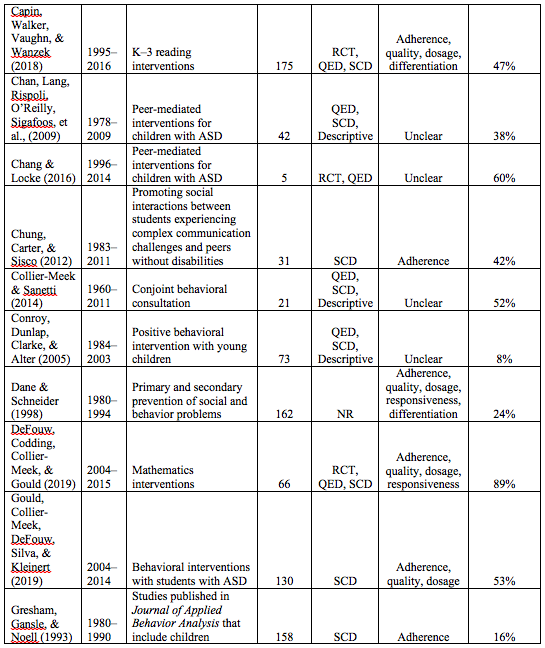

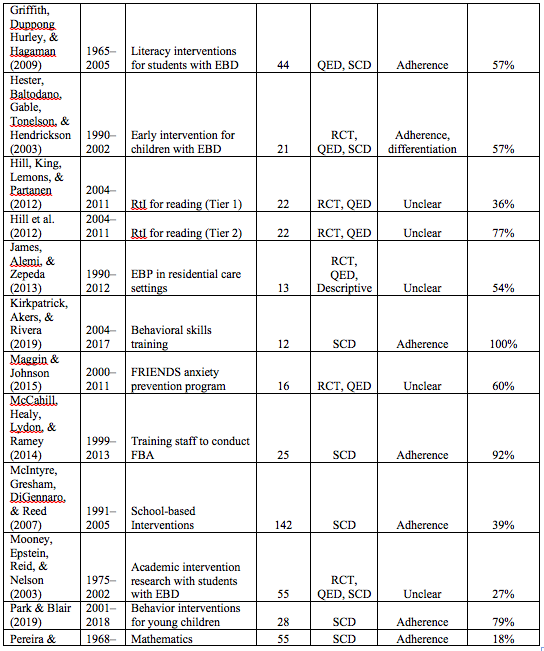

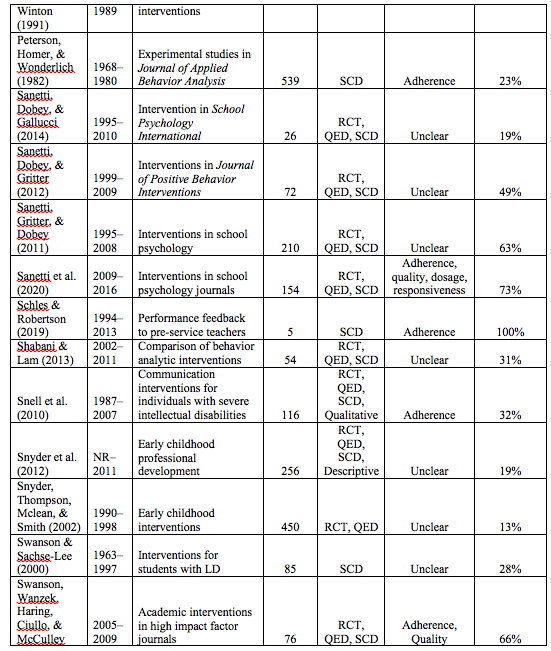

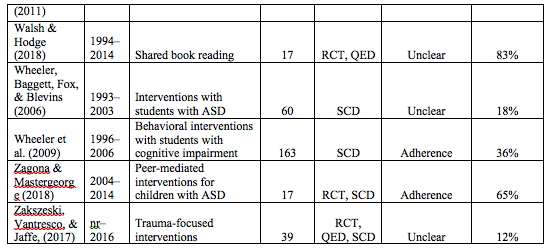

Although their work is informative, neither O’Donnell (2008) nor van Dijk et al. (2020) compared the number of studies reporting fidelity with the number of studies not reporting fidelity. Therefore, we conducted a systematic literature review to identify how often educational researchers actually report fidelity. We identified 47 reviews of educational research that reported the number of studies collecting fidelity data. Characteristics of the 47 reviews are presented in Table 1. One review, by Hill, King, Lemons, and Partanen (2012), reported fidelity for reading interventions for all students (Tier 1) and small groups of students (Tier 2) separately; therefore, we treated each as a separate review. The reviews covered a broad time frame, from 1960 to 2017, and examined a variety of topics from mathematics interventions to an anxiety prevention program. Five reviews focused exclusively on a single journal. Sixteen of the reviews focused exclusively on single-case design research, while six focused exclusively on group experimental designs. Most reviews (52%) did not make clear the type of fidelity being reported. Thirty-one percent of the reviews reported on adherence, while 19% reported on more than one type of fidelity.

Table 1.

Systematic Reviews Focused on Education-Related Topics Reporting Fidelity of Implementation

Note: ASD = autism spectrum disorder, EBD = emotional and behavioral disorder, EBP = evidence-based practice, FBA = functional behavior assessment, LD = learning disabilities, NR is not reported, QED = group-based quasi-experimental design, RCT = randomized control trial, RtI = response-to-intervention, SCD = single-case design, SEL = social-emotional learning.

The primary focus of this review of reviews was to estimate how many studies in the education-related literature reported on fidelity of implementation. Because each review includes a different number of studies, we used a weighted average to get a more precise and accurate estimate. Weights were based on the number of studies in each review. Across the 5,274 studies included in the 47 reviews, the weighted average percentage of studies reporting on fidelity of implementation was 37.4%. We then examined differences by topic of the review (e.g., applied behavior analysis), research design (e.g., single-case designs only), and years covered by the review. We found no differences in the weighted percentage of studies reporting fidelity by the topic of review or reviews that included only single-case designs. However, we found large differences based on the years covered. Forty-nine percent of studies in reviews that spanned beyond 2010 reported fidelity, while only 32% of studies in reviews prior to 2010 reported fidelity. Only 19.3% of studies in reviews prior to 2000 reported on fidelity.

A number of important findings can be gleaned from this review of reviews. First, researchers need to increasethe collection and reporting of fidelity of implementation of their independent variables. Almost two thirds of published research studies did not collect or report fidelity data. We should note that some reviews distinguished between mentioning fidelity data and collecting quantifiable fidelity data. We counted studies that mentioned or measured fidelity; therefore, fewer than two thirds reported quantitative data on fidelity of implementation.

Second, there was a clear difference across time, with more reporting of fidelity in studies published after 2010. This finding was also supported in reviews that examined differences of fidelity reporting by year. For example, Capin, Walker, Vaughn, and Wanzek, (2018) reviewed reading intervention studies conducted with students in kindergarten through third grade. The authors identified 175 published studies and dissertations. Of those, 47% reported information about fidelity of implementation. When disaggregated by years, the authors found a clear increase in the rate of fidelity reporting across time, from 27% of studies reporting fidelity in the 1990s to 61% reporting fidelity after 2010.

Unexpectedly, the domains of fidelity described and measured in the reviews were most often unclear, meaning that the review authors did not articulate a clear definition of fidelity. Of those who did provide a definition, all (100%) reported that studies collected adherence data, while 30% reported on quality. We should note that we did not disaggregate the percentage of studies within reviews reporting each fidelity domain. For example, the Sanetti et al. (2020) review examined intervention studies published in school psychology journals between 2009 and 2016. Of the 154 studies reviewed, 73% included a measure of adherence, 21% included a measure of responsiveness, 12% included a measure of dosage, and only 6% included a measure of quality.

Given that reporting on and measuring fidelity are necessary for increasing trustworthiness of study results (Gersten, Baker, Haager, & Graves, 2005; Horner et al., 2005), the scarcity of quantitative data reported is of concern. We believe that research teams should commit to collecting fidelity of implementation data across at least one dimension. However, as noted, the relationship between fidelity and outcomes is not fully established. This issue needs further research to establish the role of fidelity. Nonetheless, from a trustworthiness perspective, fidelity reporting provides evidence that the intervention was implemented and transparency about how well it was implemented.

Measurement Approaches

Once a research or practitioner team determines which dimensions of fidelity it hopes to measure, it must (1) develop a fidelity of implementation data collection approach or tool, or (2) identify an existing tool that aligns with the intervention being put into practice. The methods used to measure fidelity are critical as the tool, assessment, or system, at minimum, needs to document the presence or absence of adherence, and ideally also capture dosage, quality, differentiation, and responsiveness. Typically, fidelity measures rely on direct observation, rating scales, checklists, permanent products, interviews, and/or narrative notes. Below, we (1) describe each of these measurement approaches, (2) highlight the expanding literature in this research area, and (3) provide an example of different approaches that have been used in Schoolwide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS).

There is no right way to measure fidelity. Some advocate for one approach over another (e.g., Gresham, 2017, advocates for direct observation of fidelity), but the contextual factors associated with each intervention should drive the measurement approach. As noted, these can include checklists, rating scales, and narrative notes. Each method is often, but not always, completed by directly observing the implementation process. Direct observation is defined as the systematic collection of information about behavior (Suen & Ary, 1989). Observation can be in situ or from recordings of the implementation process.

Gersten, Baker, et al. (2005) defined three types of direct observation methods: (1) low, (2) moderate, and (3) high inference, or interpretation based on subjective perspective. A high inference observation approach is qualitative, set naturally rather than in a lab, and uses narrative reporting instead of non-numerical scaling. This approach is often used to describe the implementation process in the observer’s own words. A moderate inference observation approach requires a trained observer to make informed judgments about the quality of established, operationally defined constructs. This approach often relies on Likert scaling and requires that observers rate features of the implementation process. Moderate inferences observations can also include checklists for recording the observer’s judgment of the presence or absence of defined features of the implementation process. Finally, a low inference direct observation approach records the frequency, duration, latency, or rate of operationally defined behaviors and requires little to no inference made by the trained observer.

Measuring fidelity of implementation can also be conducted with permanent product review, qualitative interviews, or self-reporting using rating scales or checklists. Permanent product review involves the collection and coding of tangible outcomes of a behavior rather than the behavior itself (Fisher, Piazza, & Roane, 2011). For example, collecting the power points and handbooks used in a training, materials completed by implementers or students, or photos of classroom activities (e.g., the tallying marks on a whiteboard when implementing the Good Behavior Game). Coding the permanent products may involve a narrative review or a checklist or rating scale documenting the presence or absence of a critical implementation feature. Qualitative interviews can be conducted with implementers, teachers, school staff, or students and can be one-on-one or in a focus group format. The qualitative data can then be analyzed using an a priori determined qualitative method, including content analysis, case study, grounded theory, or phenomenology (Brantlinger, Jimenez, Klingner, Pugach, & Richardson, 2005). Self-reporting of fidelity typically involves an implementer or team of implementers completing a rating scale or checklist to evaluate the implementation process. Self-reports can be completed alone or in collaboration with a coach or trainer and reflect the perceptions of fidelity from those doing the implementation.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each of these measurement approaches. Some, particularly direct observations, require extensive training and time to complete, while others, like qualitative interviewing, require expertise to be done well. Another important consideration is the reliability and validity of each. Reliability is the consistency, stability, and trustworthiness of quantitative values resulting from a measure, while validity is the accuracy of inferences, interpretations, or actions made on the basis of test scores (Johnson & Christenson, 2017). It is important to note that not all reliable measures are valid; reliability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for validity (Baer, Harrison, Fradenburg, Petersen, & Milla, 2005). Reliable tests may or may not be valid, but valid tests must be reliable. For example, two observers may agree in their coding (high reliability) but what they are measuring is not what they are interested in (poor validity).

Collier-Meek, Fallon, and Gould (2018) reviewed the performance feedback literature and identified 58 studies that directly assessed fidelity. The authors then evaluated how fidelity was measured and whether or not reliability was assessed. The authors found that 76% of the studies measuring fidelity used a direct observation approach, followed by permanent product (31%), and self-report (3%).[1] The measures’ scaling approaches included present or not present (33%), Likert scale (3%), frequency counts of discrete behaviors (22%), duration (2%), and interval recording (17%). Ninety percent of the studies reported information about interobserver agreement reliability, while no studies reported on intra-observer reliability, an approach that estimates the consistency of data should a single observer observe the same behavior over and over again (Hintze, 2005 ; Suen & Ary, 1989). Further, these reliability methods can be combined in a theoretical framework known as generalizability theory, a statistical approach to evaluating reliability of a measure under different circumstances, such as number of raters, number or items, or length of observations (Shavelson & Webb, 1991; Hintze, 2005).

Gresham, Dart, and Collins (2017) used a generalizability theory approach to evaluate and compare three different fidelity measures of the Good Behavior Game. They used direct observations to evaluate the presence or absence of procedural steps, a self-report measure of the same procedural steps assessed by an observer, and permanent products (e.g., tally marks, scores) from implementation. Gresham and colleagues found that all three fidelity approaches produced acceptable reliability when measured twice weekly for 5 weeks. However, further analyses revealed that a reliable estimate from direct observations required only four observations, while permanent product fidelity required five observations, and self-report required seven observations. Correlational analyses found that direct observations and permanent product reviews significantly correlated, while direct observations and self-report did not. Essentially, the results indicate that all three methods can generate a reliable estimate, but there is little agreement between direct observation and self-report, even though both approaches used the same format.

Wilson (2017) replicated Gresham and colleagues’ study by evaluating fidelity of a response card intervention using only direct observation and self-report measures. The author created a seven-item fidelity tool that was used in both measures and conducted a generalizability study to evaluate reliability. Contrary to what occurred in the Good Behavior Game, neither direct observation or self-report resulted in a reliable measure of fidelity when conducted twice a week for 5 weeks. However, like Gresham et al., Wilson found no correlation between direct observation and self-report. It’s worth noting that Collier-Meek, Fallon, and DeFouw (2020) conducted a similar study to both Gresham et al.’s and Wilson’s comparing different dimensions of fidelity using direct observations and permanent products during Good Behavior Game implementations. However, Collier-Meek and colleagues did not use a generalizability theory approach but instead compared the methods using visual analysis and descriptive statistics. Regardless, the results were consistent, with direct observation of Good Behavior Game procedures clearly the most reliable approach to fidelity assessment.

Southam-Gerow et al. (2020) evaluated the generalizability of direct observation fidelity in two randomized controlled trials of Coping Cat (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006), a cognitive behavioral intervention. In evaluating the same fidelity tool used in research and community settings, Southam-Gerow and colleagues found that the setting accounted for the most variance and so conducted separate studies for each context. Overall, the authors found that adequate reliable and generalizable estimates of fidelity required four raters, 13 participants, and 14 sessions rated for fidelity in a research setting, and two raters, 12 participants, and 11 sessions rated for fidelity in a community setting. They noted that the resulting requirements for generalizable estimates of fidelity may not be possible given the associated costs and time and, instead, recommended development of more efficient reliable approaches to measuring fidelity.

Finally, Collier-Meek, Johnson, and Farrell (2018) developed a tool, Measure of Active Supervision and Interaction (MASI), to measure fidelity of universal behavior management implemented in out-of-school settings (e.g., afterschool programs). MASI measures the extent to which staff implemented universal behavior management, including praise and prompting for expectations. The authors evaluated reliability (e.g., interobserver agreement), generalizability, and validity (content and convergent validity). Overall, they found high reliability and that almost all of the variance was attributable to the implementer and session, which provided evidence the rater did not influence scores. As for validity, the authors found no significant correlations between MASI and other fidelity measures of universal behavior management, including a benchmarks of quality measure adapted for out-of-school settings, suggesting more work is needed to demonstrate validity.

Overall, the results from this handful of studies suggest that direct observations may be the most reliable approach, but more research is needed as the number of observations necessary to calculate a generalizable estimate may be untenable (i.e., require too many observations) and limited validity studies have been conducted. Yet, the comparisons between studies may not be appropriate given that each study focused on a different intervention with a different set of procedural and contextual components that may impact fidelity measurement. Thus, a consistent research base evaluating the psychometric properties (i.e., reliability and validity) of a fidelity tool for a single or similar intervention is needed. Until a reliable, valid, and usable observation tool is available, researchers and practitioners should continue to collect direct observations and focus on two pieces of information: stability of the fidelity measure across time and changes in student behavior. If fidelity is high (i.e., most steps/procedures correctly implemented) and student behavior changes, then it is safe to assume that the measure is accurate and valid until future evaluation is conducted.

Schoolwide Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports

One research and practice area where there has been consistent psychometric evaluation and use of fidelity tools is SWPBIS. For more than 20 years, fidelity has been an integral part of the SWPBIS implementation process (Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, Todd, & Horner, 2001).

As a result, there have been multiple measures developed and evaluated, using different measurement approaches, focused on overall implementation of the framework as well as fidelity of specific critical features of the framework. These fidelity measures include the following:

- School-Wide Evaluation Tool (SET; Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, et al., 2001)

- School-Wide Benchmarks of Quality (BoQ; Kincaid, Childs, & George, 2005, 2010)

- Effective Behavior Support Self-Assessment Survey (SAS; Sugai, Horner, & Todd, 2000)

- SWPBIS Tiered Fidelity Inventory (TFI; Algozzine et al., 2019)

- Team Implementation Checklist (TIC; Sugai, Horner, & Lewis-Palmer, 2001)

- Benchmarks for Advanced Tiers (BAT; Anderson et al., 2012)

- Individual Student Systems Evaluation Tool (ISSET; Lewis-Palmer, Todd, Horner, Sugai, & Sampson, 2003)

- Monitoring Advanced Tiers Tool (MATT; Horner, Sampson, Anderson, Todd, & Eliason, 2013)

For a complete review of fidelity measures, see George and Childs (2012) and McIntosh[GA71] et al. (2017). Below is a review of psychometric evaluations of the four [GA73] primary[C74] SWPBIS fidelity tools.

School-Wide Evaluation Tool (SET). Among the first fidelity measures develope[GA75] d to evaluate universal (Tier 1) fidelity, SET includes 28 items organized into seven subscales that represent the critical features of universal SWPBIS implementation (e.g., schoolwide expectations defined and taught to children, administrator support). The items are scored, summed overall and within each subscale, and then the percentage of points scored are calculated to quantify fidelity[C77] . The developers consider a score of 80% or greater as an indicator of fidelity. The SET is conducted by an evaluator that does not work at the school.

Benchmarks of Quality (BoQ). This 53-item self-report fidelity tool completed by a SWPBIS team, in consultation with an external coach, is designed to evaluate implementation of universal SWPBIS. BoQ provides scores for 10 subscales and an overall fidelity score. The developer[GA78] s consider a score of 70% or greater as an indicator of fidelity[C79] . The BoQ is conducted by a school’s SWPBIS team in consultation with an external coach.

Effective Behavior Support Self-Assessment Survey (SAS). This 46-item self-report fidelity tool reports on four SWPBIS domains: schoolwide systems, non-classroom systems, classroom systems, and individual student systems. SAS is completed independently and can be done by any staff member of a school. Unlike SET and BoQ, which are summative fidelity assessment tools, SAS is designed as a formative tool that can be given during the implementation process. Responses for each item are scored along two response scales: current status and priority for improvement. The tool is used for action planning and does not have a score that is considered an indicator of fidelity. The SAS is conducted by a school’s SWPBIS team.

SWPBIS Tiered Fidelity Inventory (TFI). A 45-item fidelity tool, TFI is structured around three subscales: Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 implementation. Each subscale score and total score are summed and divided by the total points possible. The developers define adequate implementation fidelity as 70%. The TFI is conducted by a school’s SWPBIS team in consultation with an external coach.

Research continues to explore the role of fidelity, not only with regard to responsiveness, but also as an implementation driver of scale-up efforts. For example, Pinkelman, Mcintosh, Rasplica, Berg, and Strickland-Cohen (2015) surveyed 860 educators to identify enablers and barriers to SWPBIS scale-up and found that evidence of fidelity was among the most highly rated enabler of SWPBIS scale-up. Research also continues to explore the measurement approaches used to evaluate SWPBIS fidelity. SET is conducted by an external evaluator who uses observations, interviews, and permanent products to score fidelity, while BoQ, TFI, and SAS are self-report measures. As noted above, convergent validity assessments among the different measures and approaches has been and continues to be conducted.

Recently, Mercer, McIntosh, and Hoselton (2017) examined convergent validity among all four of the primary SWPBIS tools. The authors found moderate convergent validity among the four fidelity tools, with all correlations statistically significant and ranging from .59 to .71, suggesting that they were generally consistent with each other, but not exactly the same. This line of research is important as it continues to highlight that diverse measurement approaches can be used to accurately identify fidelity of implementation of SWPBIS. Currently, the PBIS National Technical Assistance Center recommends that schools use TFI to measure SWPBIS fidelity because it measures implementation at all three tiers. However, if schools are implementing only Tier 1, or universal, then BoQ may be a better fit. Further, if an independent observer can collect fidelity, SET may provide relevant information for improving SWPBIS implementation.

The Importance of Implementation Fidelity

Assessing the implementation fidelity of an intervention and documenting that fidelity is important from two perspectives: (1) research design and evaluation, and (2) practical and applied. The section below highlights some of the important connections between fidelity and both research and practice. However, we should note that there are additional reasons beyond these and suggest that readers consult additional resources for a comprehensive review (e.g., Sanetti & Collier-Meek, 2019).

Fidelity plays a critical role in research design and evaluation. Perhaps most important are the connections between fidelity and internal and external validity in an experimental design study (i.e., randomized control trial) and quasi-experimental design study (two more groups compared to each other, but not randomly assigned to groups). Internal validity establishes that the results of an experiment can be attributed to what the research did; it rules out alternative explanations of study results (Kazdin, 2011). Poor implementation has a direct impact on assumptions about why something worked or didn’t work and could be the reason for a null effect[C87] , or no differences between groups. If the intervention was not implemented as prescribed, there is no reason to believe that the intervention itself is the reason that there was no difference between the groups. Alternatively, poor implementation could rule out the intervention as the reason for a positive effect (e.g., the Joslyn & Volmer study of the Good Behavior Game described above). Put differently, the effect may be spurious given that the intervention was not implemented as prescribed.

External validity is the extent to which experimental results are generalizable and can be applied across other situations (Kazdin, 2011; Shadish et al., 2002). If an intervention is implemented poorly, the likelihood that it can be successfully replicated in other settings is minimal at best.

[C89] Implementation fidelity is also critically important in practice. First, measuring and examining fidelity ensures that an intervention is being implemented correctly and confirms that student responsiveness or non-responsiveness is attributable to it. This is particularly relevant in multitiered systems of support (MTSS), including response-to-intervention (RtI) and SWPBIS. MTSS is a multi-tiered framework designed to leverage schoolwide data to identify students in need of more intensive support beyond universal supports. In RtI, universal, or tier 1, support (defined as grade-specific, evidence-based academic curriculum) is delivered to all students. Students are then periodically evaluated, ideally using curriculum-based measures, to identify those not making adequate progress and, if necessary, to deliver targeted, (tier 2), and intensive (tier 3) intervention. The entire model is contingent on accurate student-level data and assurances that the universal, targeted, and intensive supports are implemented with fidelity (Brown-Chidsey & Steege, 2011). If there is no evidence of fidelity, the decisions to provide additional support may be incorrectly applied. School personnel should collect fidelity data at all three tiers to ensure that students’ responsiveness and non-responsiveness are not confounded by fidelity concerns.

A similar concern relates to placement decisions for students with disabilities. According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [GA92] (IDEA; 2004), students with disabilities are to receive education in the least restrictive environment, which includes options ranging from the general education classroom to residential institutions (Rozlaski, Stewart, & Miller, 2010). Students with disabilities included in general education classrooms require supplemental services to allow them to successfully receive instruction. However, if those services are not implemented as prescribed, and as a result, a student isn’t making adequate educational progress, there is risk for change of placement. IDEA requires a functional behavior assessment (FBA) and, subsequently, an FBA-based intervention before a change in placement can made based on the presence of challenging behaviors. Fidelity of that FBA-based intervention should be typical practice when implemented to ensure response or non-response was due to the intervention, not the implementation of the intervention.

Measurement of fidelity in practice is also important for evaluating the need for additional professional development. There are myriad evidence-based academic and behavioral intervention protocols that school staff can leverage (https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc), but each must be implemented as designed to achieve the desired effects. Thus, the process of measuring fidelity (particularly adherence, quality, and dosage) can identify gaps in implementation where professional development can be delivered to increase fidelity. Some fidelity tools are designed with professional development in mind. For example, TFI (https://www.pbis.org/resource/tfi) includes specific, actionable guidance for connecting each fidelity indicator to professional development resources.

Implications

Guidance for Researchers

Much work needs to be done to increase development, measurement, and use of fidelity in research. It is concerning that almost two thirds of published experimental research studies did not collect or report fidelity data. Certainly, the requirement to design and collect fidelity by some funding agencies (e.g., IES) appears to have an impact, with increased prevalence of fidelity reporting in the past 10 years. Still, there are other changes that could further increase fidelity reporting. For example, journal editors should establish clear guidelines that experimental research studies must report fidelity or justify why fidelity was not collected. In fact, the Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS; https://apastyle.apa.org/jars/quant-table-2.pdf) from the American Psychological Association (APA), used by many journals (e.g., Exceptional Children), requires fidelity reporting.

Another area of focus should be the education and professional development of researchers. Doctoral programs should incorporate fidelity of implementation into research design courses and give workshops on the importance of fidelity and methods of collecting fidelity data. Similarly, professional meetings should include workshops on fidelity. These professional development activities could also highlight the importance of operationally defined independent variables, training manuals, and explicit implementation protocols. Last, we agree with Gresham (2017) and want to see a “science of fidelity of implementation” developed and proliferated. Certainly, the on-going work of Lisa Sanetti, Melissa Collier-Meek, and Frank Gresham, as well as the expanding SWPBIS fidelity research, are models for this science. We strongly advocate that others contribute to this space and continue to grow our knowledge and resources to increase fidelity use and reporting.

Guidance for Practitioners

Although fidelity is important, it is not always easy to collect. This is particularly true in practice, where educators have limited time, resources, and capacity. Adding fidelity assessment to the complex process of beginning a new system, practice, or intervention may not always appear feasible. Nonetheless, there needs to be a commitment to identifying ways to increase measurement of fidelity in order to increase fidelity of implementation. First, school staff should consider fidelity tools when deciding on an intervention and either request fidelity tools from the developers of the intervention or work with either an external partner or internal team to develop an approach to measure fidelity.

Fidelity can be collected in a number of ways. Although direct observation appears to be the most accurate approach, permanent products and self-report checklists can and should be considered. If the new practice has an established tool, school staff should incorporate that measure into the implementation process. Further, if external supports are available, schools should work with them to ensure fidelity measurement. Some professional development organizations make access to support contingent on fidelity measurement. For example, the Florida Positive Behavior Intervention and Support Project provides continuous support for schools initiating and implementing SWPBIS and, as part of that support, requires all schools to complete and submit BoQ annually.

An additional concern at the practice level is the need to increase implementation fidelity. Detrich (2014) provided a succinct review of strategies to increase fidelity. He suggested that efforts need to be made to increase the acceptability and contextual fit of a new intervention. One way is to involve school staff in making decisions about interventions or procedures for implementation. Second, he suggested that professional development be explicit and evidence based, and that it include ongoing coaching support. Last, implementers should receive feedback that ideally is visual and provides suggestions for increasing or decreasing specific behaviors (Ennis et al., 2018).

Practitioners should receive professional development focused on the importance of fidelity of implementation and methods for leveraging fidelity in their practice. This professional development should be both pre-service and in-service. One freely available internet resource is the IRIS Center, supported by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs and located at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College. It develops and disseminates free online resources about evidence-based instructional and behavioral practices (https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/). Although no single fidelity module is available, fidelity is incorporated into many of the modules, including those focused on behavior and classroom management, MTSS, and school improvement.

Guidance for Policymakers

As much as practitioner commitment can bridge the fidelity divide, policymakers at the district and state levels can have a significant impact on fidelity collection. First, policymakers should require curriculum and intervention developers to include fidelity approaches with new programs. By placing such a requirement on developers prior to purchase, the developers will be highly motivated to ensure that fidelity is a part of the development and distribution process. Second, policymakers should establish policies and statewide recommendations focused on fidelity. For example, the California Department of Education provides information and resources about fidelity of implementation and describes it as a core component of MTSS (https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/cr/ri/corecomp7.asp). State and district policymakers should also consider codifying fidelity requirements. In essence, state and district policymakers need to create a districtwide and statewide culture of fidelity, in which the collection and reporting of fidelity are accepted parts of educational practice.

Conclusions

Fidelity of implementation is a critical but often neglected component of any new system, practice, or intervention in educational research and practice. Fidelity is a multidimensional construct focused on providing evidence of adherence, quality, dosage, differentiation, and responsiveness following implementation. Unfortunately, fidelity has not always been prioritized, although evidence suggests that is changing, at least in published research. Further, although there are myriad methods for measuring fidelity, psychometric evaluations of fidelity tools have been limited, except in the SWPBIS literature. Calls for a science of fidelity have been made (Gresham, 2017) and are beginning to be answered. Overall, there appears to be more research focused exclusively on fidelity, including measurement approaches, psychometric evaluations, and relation to outcomes. As this research expands, we hope that the broad use and integration of fidelity in practice follows. We believe that the days of neglecting fidelity are behind us in education and see fidelity playing a central role in education moving forward. Through reliable and valid measurement of fidelity, scalable evidence-based practices can be developed and proliferated, positively impacting students’ academic and behavioral outcomes.

Citations

*included in review of reviews

Algozzine, B., Barrett, S., Eber, L., George, H., Horner, R., Lewis, T., Putnam, B., Swain-Bradway, J., McIntosh, K., & Sugai, G (2019). School-wide PBIS Tiered Fidelity Inventory. OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. www.pbis.org.

Allinder, R. M., Bolling, R. M., Oats, R. G., & Gagnon, W. A. (2000). Effects of teacher self-monitoring on implementation of curriculum-based measurement and mathematics computation achievement of students with disabilities. Remedial & Special Education, 21, 219–227.

Anderson, C. M., Childs, K., Kincaid, D., Horner, R. H., George, H., Todd, A. W., . . .Spaulding, S. A. (2012). Benchmarks for Advanced Tiers. Unpublished instrument, Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon & University of South Florida.

*Andzik, N. R., Cannella-Malone, H. I., & Sigafoos, J. (2016). Practitioner-implemented functional communication training: A review of the literature. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(2), 79-89.

*Armstrong, K.J., Ehrhardt, K.E., Cool, R.T. et al. Social Validity and Treatment Integrity Data: Reporting in Articles Published in the Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 1991-1995. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 9, 359–367 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024982112859

Baer, D. M., Harrison, R., Fradenburg, L., Petersen, D., & Milla, S. (2005). Some pragmatics in the valid and reliable recording of directly observed behavior. Research on Social Work Practice, 15(6), 440-451. DOI: 10.1177/1049731505279127

*Baril, E. M., & Humphreys, B. P. (2017). An Evaluation of the Research Evidence on the Early Start Denver Model. Journal of Early Intervention, 39(4), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815117722618

*Barnes, T. N. (2019). Changing the Landscape of Social Emotional Learning in Urban Schools: What are We Currently Focusing On and Where Do We Go from Here?. The Urban Review, 51(4), 599-637.

Berman, P. & McLaughlin, M. W. (1974). Federal programs supporting educational change, Vol. 1: A model of educational change. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED099957.pdf

*Biel, C. H., Buzhardt, J., Brown, J. A., Romano, M. K., Lorio, C. M., Windsor, K. S., ... & Goldstein, H. (2020). Language interventions taught to caregivers in homes and classrooms: A review of intervention and implementation fidelity. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 140-156.

Blackely, C. H., Mayer, J. P., Gottschalk, R. G., Schmitt, N., Davidson, W. S., Roitman, D. B., & Emshoff, J. G. (1987). The fidelity-adaptation debate: Implications for the implementation of public sector social programs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15, 253-268.

*Bohaty, J. J., Hebert, M. A., Nelson, J. R., & Brown, J. A. (2015). Methodological Status and Trends in Expository Text Structure Instruction Efficacy Research. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 54(2). Retrieved fromhttps://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol54/iss2/3

*Bozkus-Genc, G., & Yucesoy-Ozkan, S. (2016). Meta-analysis of pivotal response training for children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51(1), 13-26.

Brand, D., Henley, A. J., DiGennaro Reed, F. D., Gray, E., & Crabbs, B. (2019). A review of published studies involving parametric manipulations of treatment integrity. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28(1), 1–26. doi:10.1007/s10864-018-09311-8

Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., & Richardson, V. (2005). Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional children, 71(2), 195-207.

Brown-Chidsey, R., & Steege, M. W. (2011). Response to intervention: Principles and strategies for effective practice. Guilford Press.

Bruckner, C. T., Yoder, P. J., & McWilliam, R. A. (2006). Generalizability and decision studies: An example using conversational language samples. Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 139-153.

*Bruhn, A. L., Hirsch, S., & Lloyd, J. W. (2015). Treatment integrity in school-wide programs: A review of the literature (1993-2012). Journal of Primary Prevention, 36, 335-349. Doi. 10.1007/s10935-015-0400-9

*Capin, P., Walker, M. A., Vaughn, S., & Wanzek, J. (2018). Examining how treatment fidelity is supported, measured, and reported in K–3 reading intervention research. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 885–919. doi:10.1007/s10648-017-9429-z

Century, J., & Cassata, A. (2016). Implementation research: Finding common ground on what, how, why, where, and who. Review of Educational 40, 169-215. DOI: 10.3102/0091732X16665332

*Chang, Y. C., & Locke, J. (2016). A systematic review of peer-mediated interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 27, 1-10.

*Chan, J. M., Lang, R., Rispoli, M., O’Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., & Cole, H. (2009). Use of peer-mediated interventions in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 3(4), 876-889.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.04.003

*Chung, Y. C., Carter, E. W., & Sisco, L. G. (2012). A systematic review of interventions to increase peer interactions for students with complex communication challenges. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37(4), 271-287.

*Collier-Meek, M. A., Fallon, L. M., & Gould, K. (2018). How are treatment integrity data assessed? Reviewing the performance feedback literature. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(4), 517.

Collier-Meek, M. A., Fallon, L. M., & DeFouw, E. R. (2020). Assessing the Implementation of the Good Behavior Game: Comparing Estimates of Adherence, Quality, and Exposure. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 45(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508418782620

Collier-Meek, M. A., Johnson, A. H., & Farrell, A. F. (2018). Development and initial evaluation of the Measure of Active Supervision and Interaction. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 43(4), 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508417737516

*Collier-Meek, M. A., & Sanetti, L. M. (2014). Assessment of consultation and intervention implementation: A review of conjoint behavioral consultation studies. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 24(1), 55-73.

*Conroy, M. A., Dunlap, G., Clarke, S., & Alter, P. J. (2005). A descriptive analysis of positive behavioral intervention research with young children with challenging behavior. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 25(3), 157-166.

Crocker, L., & Algina, J. (1986). Introduction to classical and modern test theory. Fort

Worth, TX: Harcourt.

*Dane, A. V., & Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control?. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3

*DeFouw, E. R., Codding, R. S., Collier-Meek, M. A., & Gould, K. M. (2019). Examining dimensions of treatment intensity and treatment fidelity in mathematics intervention research for students at risk. Remedial and Special Education, 40(5), 298-312.

Detrich, R. (2014). Treatment integrity: Fundamental to education reform. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 14, 258-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.13.2.258

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E .P. (2008) Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology 41, 327 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to Implementation Science. Implementation Science, 1(1),1–3. Retrieved from http://www.implementationscience.com/content/1/1/1

Ennis, R. P., Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., & Dunlap, K. D. (2018). The Impact of Coaching on Teacher-Delivered Behavior-Specific Praise in Pre-K-12 Settings: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Disorders, 0198742919839221.

Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., & Roane, H. H. (2011). Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. (FMHI Publication No. 231). University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National IMPLEMENTATION Research Network.

George, H. P., & Childs, K. E. (2012). Evaluating implementation of schoolwide behavior support: Are we doing it well. Preventing School Failure, 56, 197-206. Doi. 10.1080/1045988X.2011.645909

Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., Haager, D., & Graves, A. W. (2005). Exploring the role of teacher quality in predicting outcomes for first-grade English learners: An observational study. Remedial and Special Education, 26, 197–206.

Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., & Innocenti, M. S. (2005). Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional children, 71(2), 149-164.

*Gould, K. M., Collier-Meek, M., DeFouw, E. R., Silva, M., & Kleinert, W. (2019). A systematic review of treatment integrity assessment from 2004 to 2014: Examining behavioral interventions for students with autism spectrum disorder. Contemporary School Psychology, 1-11.

Gresham F. M. (1989). Assessment of treatment integrity in school consultation and prereferral intervention. School Psychology Review, 18, 37–50.

Gresham, F. M. (2017). Features of fidelity in schools and classrooms: Constructs and measurement. In G. Roberts, S. Vaughn, S. N. Beretvas, & V. Wong (Eds.). Treatment fidelity in students of educational intervention (pp. 22-38). New York: Routledge.

Gresham, F.M., Dart, E., & Collins, T. (2017). Generalizability of multiple measures of treatment integrity: Comparisons among direct observations, permanent products, and self-report. School Psychology Review, 46(1), 108-121.

*Gresham, F. M., Gansle, K. A., & Noell, G. H. (1993). Treatment integrity in applied behavior analysis with children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(2), 257-263.

*Griffith, A. K., Duppong Hurley, K., & Hagaman, J. L. (2009). Treatment Integrity of Literacy Interventions for Students With Emotional and/or Behavioral Disorders: A Review of Literature. Remedial and Special Education, 30(4), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932508321013

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. (2017). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, & mixed approaches (6th Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Hall, G. E., & Loucks, S. F. (1977). A developmental model for determining whether the treatment is actually implemented. American Educational Research Journal,14, 263–276.

Hedges, L. V. (2018). Challenges in building usable knowledge in education. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(1), 1-21.

*Hester, P. P., Baltodano, H. M., Gable, R. A., Tonelson, S. W., & Hendrickson, J. M. (2003). Early intervention with children at risk of emotional/behavioral disorders: A critical examination of research methodology and practices. Education and Treatment of Children, 362-381.

*Hill, D. R., King, S. A., Lemons, C. J., & Partanen, J. N. (2012). Fidelity of implementation and instructional alignment in response to intervention research. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 27(3), 116-124.

Hintze, J. M. (2005). Psychometrics of direct observation. School Psychology Review, 34(4), 507-519.

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional children, 71(2), 165-179.

Horner, R. H., Sampson, N. K., Anderson, C. M., Todd, A. W., & Eliason, B. M. (2013). Monitoring Advanced Tiers Tool. Eugene: Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon.

Horner, R. H., Todd, A. W., Lewis-Palmer, T., Irvin, L. K., Sugai, G., & Boland, J. B. (2004). The School-Wide Evaluation Tool (SET): A Research Instrument for Assessing School-Wide Positive Behavior Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/10983007040060010201

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

Institute for Education Sciences. (2020).Request for Applications: Education Research Grants. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/funding/pdf/2021_84305A.pdf

*James, S., Alemi, Q., & Zepeda, V. (2013). Effectiveness and implementation of evidence-based practices in residential care settings. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(4), 642-656.

Joslyn, P. R., & Vollmer, T. R. (2020). Efficacy of teacher‐implemented good behavior game despite low treatment integrity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(1), 465-474. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.614

Kazdin, A. E. (1986). Comparative outcome studies of psychotherapy: Methodological issues and strategies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 95-105.

Kazdin, A. E. (2011). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied

settings (2nd Ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Keller-Margulis, M. A. (2012). Fidelity of implementation framework: A critical need for response to intervention models. Psychology in the Schools, 49, 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21602

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual. Ardmore, PA: Workbook.

Kincaid, D., Childs, K., & George, H. (2005). School-wide benchmarks of quality. Unpublished instrument, University of South Florida

Kincaid, D., Childs, K., & George, H. (March, 2010). School-wide benchmarks of quality (Revised). Unpublished instrument. USF, Tampa, Florida. Retrieved from https://www.pbis.org/resource/benchmarks-of-quality-boq-scoring-form

*Kirkpatrick, M., Akers, J., & Rivera, G. (2019). Use of Behavioral Skills Training with Teachers: A Systematic Review. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28(3), 344-361.

Lewis-Palmer, T., Todd, A. W., Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Sampson, N. K. (2003). Individual Student Systems Evaluation Tool (ISSET). Eugene, OR: Educational and Community Supports.

*Maggin, D. M. & Johnson, A. H. (2015) The Reporting of Core ProgramComponents: An Overlooked Barrier for Moving Research Into Practice, Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59:2, 73-82, DOI: 10.1080/1045988X.2013.837812

Massar, M. M., McIntosh, K., & Mercer, S. H. (2019). Factor Validation of a Fidelity of Implementation Measure for Social Behavior Systems. Remedial and Special Education, 40(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932517736515

*McCahill, J., Healy, O., Lydon, S., & Ramey, D. (2014). Training educational staff in functional behavioral assessment: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 26(4), 479-505.

McIntosh, K., Massar, M. M., Algozzine, R. F., George, H. P., Horner, R. H., Lewis, T. J., & Swain-Bradway, J. (2017). Technical Adequacy of the SWPBIS Tiered Fidelity Inventory. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300716637193

*McIntyre, L. L., Gresham, F. M., DiGennaro, F. D., & Reed, D. D. (2007). Treatment integrity of school-based interventions with children in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 1991-2005. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(4), 659–672.

Mercer, S. H., McIntosh, K., & Hoselton, R. (2017). Comparability of Fidelity Measures for Assessing Tier 1 School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(4), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717693384

Moncher, F. J., & Prinz, R. J. (1991). Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 11(3), 247–266.

*Mooney, P., Epstein, M. H., Reid, R., & Nelson, J. R. (2003). Status of and trends in academic intervention research for students with emotional disturbance. Remedial and Special Education, 24(5), 273-287.

Naleppa, M. J., & Cagle, J. G. (2010). Treatment Fidelity in Social Work Intervention Research: A Review of Published Studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(6), 674–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509352088

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53–66. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

O’Donnell, C. L. (2008). Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring fidelity of implementation and its relationship to outcomes in K–12 curriculum intervention research. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 33–84. doi:10.3102/0034654307313793

*Park, E. Y., & Blair, K. S. C. (2019). Social Validity Assessment in Behavior Interventions for Young Children: A Systematic Review. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 39(3), 156-169.

Penuel, R., & Means, B. (2004). Implementation variation and fidelity in an inquiry science program: Analysis of GLOBE data reporting patterns. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41, 294–315.

*Peterson, L., Homer, A. L., & Wonderlich, S. A. (1982). The integrity of independent variables in behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 15(4), 477–492.

*Pereira, J. A., & Winton, A. S. (1991). Teaching and remediation of mathematics: A review of behavioral research. Journal of Behavioral Education, 1(1), 5-36.

Pinkelman, S. E., Mcintosh, K., Rasplica, C. K., Berg, T., & Strickland-Cohen, M. K. (2015). Perceived Enablers and Barriers Related to Sustainability of School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Behavioral Disorders, 40(3), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.17988/0198-7429-40.3.171

*Sanetti, L. M. H., Charbonneau, S., Knight, A., Cochrane, W. S., Kulcyk, M. C., & Kraus, K. E. (2020). Treatment fidelity reporting in intervention outcome studies in the school psychology literature from 2009 to 2016. Psychology in the Schools, 57(6), 901-922.

Sanetti, L. M. H., & Collier-Meek, M. A. (2019). Supporting successful interventions in schools: Tools to plan, evaluate, and sustain effective implementation. New York: Guilford Press.

*Sanetti, L. M. H., Dobey, L. M., & Gallucci, J. (2014). Treatment integrity of interventions with children in School Psychology International from 1995–2010. School Psychology International, 35(4), 370-383.

*Sanetti, L. M. H., Dobey, L. M., & Gritter, K. L. (2012). Treatment integrity of interventions with children in the Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions from 1999 to 2009. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(1), 29-46.

*Sanetti, H. L. M., Gritter, K. L., & Dobey, L. M. (2011). Treatment integrity of interventions with children in the school psychology literature from 1995 to 2008. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 72-84.

Sanetti, L. M. H., & Kratochwill, T. R. (2009). Toward developing a science of treatment integrity: Introduction to the special series. School Psychology Review, 38(4), 445-459.

Sanetti, L. M. H., & Luh, H.-J. (2019). Fidelity of implementation in the field of learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 42(4), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948719851514

*Schles, R. A., & Robertson, R. E. (2019). The role of performance feedback and implementation of evidence-based practices for preservice special education teachers and student outcomes: A review of the literature. Teacher Education and Special Education, 42(1), 36-48.

*Shabani, D. B., & Lam, W. Y. (2013). A review of comparison studies in applied behavior analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 28(2), 158-183.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental

designs for generalized causal inference. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Shavelson, R. J., & Webb, N. M. (1991). Generalizability theory: A primer. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage.

*Snell, M. E., Brady, N., McLean, L., Ogletree, B. T., Siegel, E., Sylvester, L., ... & Sevcik, R. (2010). Twenty years of communication intervention research with individuals who have severe intellectual and developmental disabilities. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities, 115(5), 364-380.

*Snyder, P., Hemmeter, M. L., Meeker, K. A., Kinder, K., Pasia, C., & McLaughlin, T. (2012). Characterizing key features of the early childhood professional development literature. Infants & Young Children, 25(3), 188-212.

*Snyder, P., Thompson, B., Mclean, M. E., & Smith, B. J. (2002). Examination of quantitative methods used in early intervention research: Linkages with recommended practices. Journal of Early Intervention, 25(2), 137-150.

Songer, N. B., & Gotwals, A. W. (2005, April). Fidelity of implementation in three sequential curricular units. In S. Lynch (Chair) & C. L. O’Donnell, “Fidelity of implementation” in implementation and scale-up research designs: Applications from four studies of innovative science curriculum materials and diverse populations. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, Canada.

Southam-Gerow, M. A., Bonifay, W., McLeod, B. D., Cox, J. R., Violante, S., Kendall, P. C., & Weisz, J. R. (2020). Generalizability and Decision Studies of a Treatment Adherence Instrument. Assessment, 27(2), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118765365

Suen, H. K., & Ary, D. (1989). Analyzing quantitative behavioral observation data Hillsdale, NJ: LEA.

Sugai, G., Lewis-Palmer, T., Todd, A., & Horner, R. H. (2001). School-wide evaluation tool. Eugene: University of Oregon.

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., & Lewis-Palmer, T. L. (2001). Team Implementation Checklist (TIC). Eugene, OR: Educational and Community Supports. Available from http://www.pbis.org

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., & Todd, A. W. (2000). Effective behavior support: Self-assessment survey. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon.

*Swanson, H. L., & Sachse-Lee, C. (2000). A meta-analysis of single-subject-design intervention research for students with LD. Journal of learning disabilities, 33(2), 114-136.

*Swanson, E. A., Wanzek, J., Haring, C., Ciullo, S., & McCulley, L. (2011). Intervention fidelity in special and general education research journals. The Journal of Special Education, 47(1), 3–13.

Unlu, F., Bozzi, L., Layzer, C., Smith, A., Price, C., & Hurtig, R. (2017). Linking implementation fidelity to impacts in an RCT. In G. Roberts, S. Vaughn, S. N. Beretvas, & V. Wong (Eds.). Treatment fidelity in students of educational intervention (pp. 100-129). New York: Routledge.

Van Dijk, W., Gage, N. A., & Lane, H. (2020). The relation between implementation fidelity and students’ reading outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Reading Research Quarterly.

*Walsh, R. L., & Hodge, K. A. (2018). Are we asking the right questions? An analysis of research on the effect of teachers’ questioning on children’s language during shared book reading with young children. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 18(2), 264-294.

Ward, B. & Gersten, R. (2013), A randomized evaluation of the Safe and Civil Schools model for positive behavioralinterventions and supports at elementary schools in a large urban school district. School Psychology Review, 42(3), 317-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2013.12087476

*Wheeler, J. J., Mayton, M. R., Carter, S. L., Chitiyo, M., Menendez, A. L., & Huang, A. (2009). An assessment of treatment integrity in behavioral intervention studies conducted with persons with mental retardation. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 187-195.