Active Student Responding (ASR) Overview

Active Student Responding Overview PDF

States, J., Detrich, R. & Keyworth, R. (2019). Active Student Responding (ASR) Overview.Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/instructional-delivery-student-respond

For decades there have been serious concerns that the nation’s schools aren’t living up to expectations (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983). Over 40 years of data from the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) reveal that more than 60% of American students have been performing below proficiency, and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) shows students in the United States falling behind peers from many of the world’s developed nations (Nation’s Report Card, 2017; PISA, 2015).

The knowledge base of what works and what doesn’t when it comes to improving student outcomes is growing. The abundance and quality of studies now offer educators and policymakers sufficient data to make informed choices to change this picture (Slavin, 2019). Research supports the conclusion that much of the past reforms missed the target and focused on practices with a track record of having only modest effects on student outcomes (States, Detrich, & Keyworth, 2012). Strong evidence supports reforms directed at what happens in the classroom, improving how teachers teach. The data are clear: Effective instruction outweighs all other factors under the control of the school system, closely followed by evidence-based strategies that offer guidelines on how to implement and sustain these practices (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, & Friedman, 2005; Hattie, 2012). One of the more powerful instructional interventions that fits this requirement and is backed by clinical research is active student responding (ASR), which not only improves academic achievement but is simple in concept and easy for teachers to implement (Heward & Wood, 2015).

What Is Active Student Responding?

ASR is a powerful set of flexible, low-cost strategies to improve student achievement and decrease inappropriate conduct by increasing active student engagement in the learning process (Armendariz & Umbreit, 1999; Ellis, Worthington, & Larkin, 1994; Godfrey, Grisham-Brown, Schuster, & Hemmeter, 2003; Haydon et al., 2010; Swanson & Hoskyn, 2001; Tincani, 2011; Wood, Mabry, Kretlow, Lo, & Galloway, 2009).ASR increases participation by requiring each pupil to provide multiple responses during instruction (Jerome & Barbetta, 2005). In ASR, teachers ask questions or provide instructions that require every student to write an answer or provide an oral reply. These responses increase opportunities for students to rehearse the material covered in the lesson, provide the teacher with a quick assessment of each pupil’s current proficiency, and give the teacher the necessary information for how and when to adjust instruction to maximize learning for all children.

ASR Practice Elements

ASR comprises three well-supported practice elements: (1) ample opportunities for students to actively practice a lesson, (2) frequent opportunities for students to reveal newly acquired skills or knowledge through observable responses the teacher can use to assess a learner’s current level of mastery of the material, and (3) increased frequency of feedback by the teacher to each student (Heward & Wood, 2015).

Practice. The old saying “Practice makes perfect” has support in research. The more opportunities a student has to practice a skill or acquire knowledge, the greater the likelihood the lesson will be successfully mastered (Donovan & Radosevich, 1999). A 2014 meta-analysis found that practice was a strong overall predictor of success and that people who practiced a lot generally tended to perform at a higher level than people who practiced less (Macnamara, Hambrick, & Oswald, 2018). Research on typical class instruction method suggests that when teachers call on students one at a time, each student actively participates for less than a minute each hour (Kagan & Kagan, 2009).

This low rate of engagement provides insufficient opportunities for a pupil to practice acquiring knowledge or to master a new skill. But how much practice is enough? Students frequently require three or four exposures to learn a lesson (Nuthall, 2005). The more opportunities students have to practice, the more likely they are to learn and for that learning to endure. When knowledge or skills are not used, they are lost (Ebbinghaus, 2013; Smith, Floerke, & Thomas, 2016). A productive regimen of practice and feedback provides students with time between practice sessions (spaced practice), a more effective approach than requiring students to practice over longer sessions (massed practice) (Donovan & Radosevich, 1999).

Too much practice is rarely a problem in schools, but excess practice should be controlled to make the best use of the available instructional time (Chard & Kame’enui, 2000; Stichter et al., 2009). One study found that having students actively respond to spelling words 10 or 15 times was no more effective that than having students practice five times (Cuvo, Ashley, Marso, Bingju, & Fry, 1995). Finding the sweet spot for the best dosage of practice needed to maximize academic achievement and minimize unnecessary practice is ultimately a win-win for both teacher and students and is an area in need of further study.

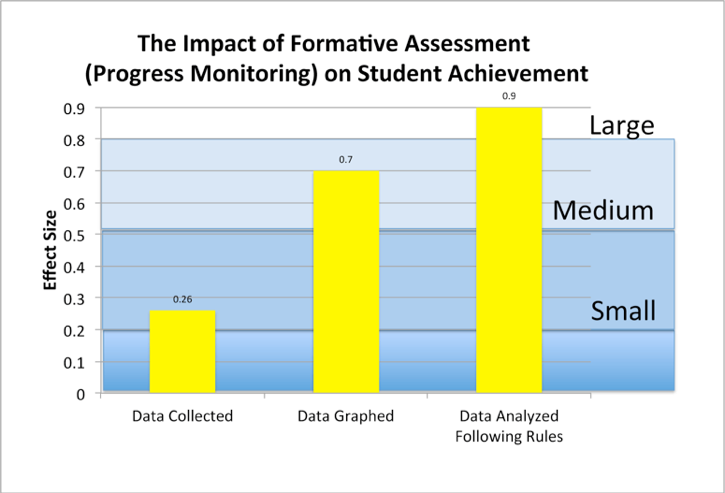

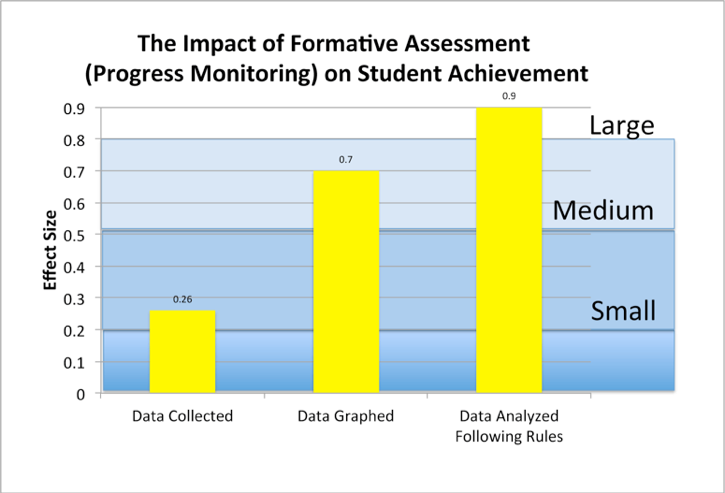

Formative Assessment. Increasing the number of active student responses not only provides more opportunities to practice but permits teachers to rapidly assess performance. Research on ongoing progress monitoring (formative assessment) suggests this form of assessment has a large 0.90 effect size on learning (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986). The Fuchs and Fuchs study found that the power of formative assessment was enhanced by teachers collecting data, graphing the data, and taking the time to analyze the information following guidelines. When students have more active opportunities to respond, teachers gain more information on each student’s performance. Accurate information on each student’s status in the mastery of a lesson can guide the teacher in adapting instruction to meet each student’s needs.

Figure 1. Effects of systematic formative evaluation (Fuchs and Fuchs, 1986)

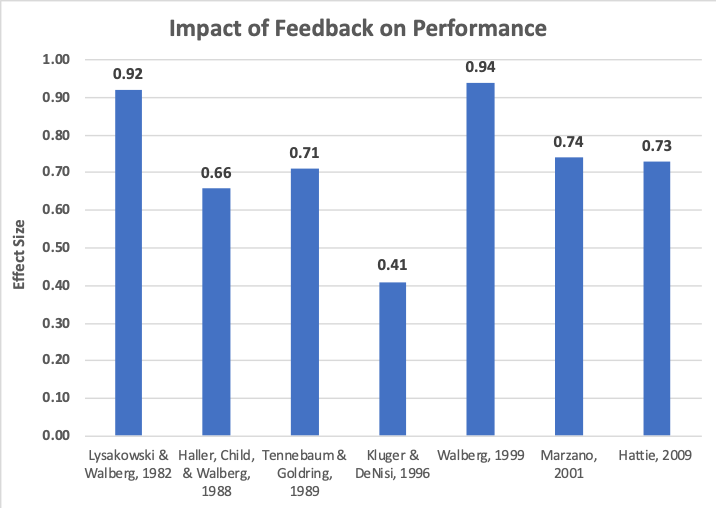

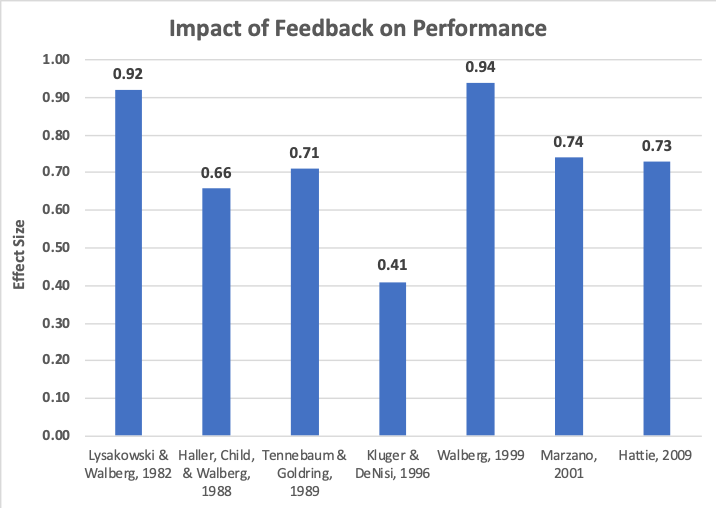

Feedback. ASR increases the opportunities for a teacher to provide feedback that is better matched to the needs of each pupil. Feedback has the effect of augmenting the power of ASR as it is among the most powerful practices available for improving student achievement, with an effect size of 0.73 (Hattie, 2009). It provides information to teachers and students about both the quality and accuracy of student responses (Cleaver, Detrich, & States, 2019). A substantial body of research strongly supports the power of feedback to improve academic performance. Figure 2 highlights seven meta-analyses on the use of feedback and its effect on performance. They show that feedback can have a significant impact; in fact, six of the seven meta-analyses reveal medium to large effect sizes. The Kluger and DeNisi (1996) research, which found the smallest effect size (0.41), showed that one third of the studies it reviewed produced negative outcomes. When feedback was perceived to be directed at the person, performance was negatively impacted, but when feedback was focused on the task at hand, performance improved. The takeaway lesson: For feedback to have the greatest positive impact on student outcomes, teachers need to be trained in how to deliver it.

Figure 2. Impact of feedback derived from seven meta-analyses

Sample of Active Student Responding Strategies

Active student responding consists of a range of strategies designed to promote student engagement (Jerome & Barbetta, 2005). These strategies can be classified according to the response mode required of the students: written response, oral response, or action.

An example of a common ASR practice is the use of response cards. Their use can help to explain what ASR is and how it can work in the classroom.

Response Cards

This way of actively engaging students in learning enables teachers to easily assess student learning. Response card activities require all students in the class to write their responses to a question on a card or to choose answers on preprinted cards.

Lesson

Grade 5 social studies standard: Students learn to identify the capital of each state and its general location on a map.

- The teacher poses a question that requires a response. (e.g., The teacher points to West Virginia on a map of the United States and asks, “What is the capital of West Virginia?”)

- Students are given time to think of a response and then write it on a card.

- The teacher prompts students to reveal their answers by holding up the card. (“Show me your answer!”)

- The teacher assesses the responses.

- The teacher provides feedback (“Correct answer! The capital is Charleston.”)

- The teacher instructs students to correct the answer if wrong and provides additional instruction when necessary.

Below is a listing of common ASR strategies.

Guided Notes. These notes are designed to increase active student engagement and, in turn, increase academic performance and facilitate success in school. Note taking isn’t often taught and students have been found to be poor note takers (Boyle & Forchelli, 2014).Guided notes help remediate this situation by providing students with teacher-prepared materials that guide them through a lecture. Guided notes use prompted cues and prepared spaces for students to write facts, concepts, and/or relationships, making note taking more effective (Heward, 1994; Konrad, Joseph, & Itoi, 2011; Tincani, 2011).

Response Cards. Requiring all students to answer questions that a teacher poses by writing their answers on a card has been shown to maximize engagement (Heward, 1994; Tincani, 2011).Response cards offer instructors a low-tech option for engaging students in the lesson, and they allow teachers to assess each student’s performance. During instruction, the teacher stops and delivers a cue for students to write a response to a question or issue pertaining to the lesson. All students are required to answer on a card, slate, board, or electronic performance system. All the students show their answers to the teacher. This strategy gives students increased opportunities to actively respond and receive feedback in addition to providing the teacher with information on each student’s movement toward mastery of the material (Pearce, 2011).

A variation consists of preprinted response cards. Students reveal responses by revealing a card that offers such options as true/false, yes/no, or noun/verb/adverb/adjective.

Think-Write-Pair-Share. This strategy is designed to provide students with increased opportunities to practice critical thinking through interactions with peers. Students are grouped into pairs. The teacher provides a prompt or question to the class, and the students write their responses. Each student pair is asked to share their answers with each other. Then the teacher invites one or more pairs to share their responses with the whole group or class. The strategy increases engagement through sharing ideas with peers. This is an improvement over the commonly employed recitation method in which a teacher poses a question and only one student offers a response (Kothiyal, Majumdar, Murthy, & Iyer, 2013; Simon, 2019).

Time Trials. The teacher describes an assignment and specifies the time allocated for completing it. The teacher signals for students to start writing their answers and tells them when time is up, at which point the students stop writing. Then the students show their results to the teacher and their peers, and record their own progress (Pearce, 2011).

Four Corners. This technique stimulates learning through movement and discussion. The class is presented with a statement or question about what is being studied. The teacher prompts or asks a question, and each student writes a response. The teacher labels the four corners of the room with a relevant word or phrase, and students go to the corner that corresponds with their opinions or responses. The students in each corner review their answers and discuss the issue (FacingHistory.org; Theteachertoolkit.com).

Show Me. This low-cost and low-effort strategy offers all students the opportunity to be engaged and respond to a teacher’s question. The instructor asks the students to respond by signaling (thumbs up, down, sideways; hold up number of fingers, etc.). This strategy gives a teacher immediate feedback on a student’s understanding of the material being presented.

Choral Responding. This method, which requires all students to respond in unison to teacher questions, uses brisk instructional pacing to increase engagement (Heward & Wood, 2015; Tincani & Twyman, 2016). It can be used with the whole class or adapted for small groups. Choral responding increases active responding and has the added benefit of reducing student disruptive behavior compared with the traditional raising of hands (Haydon, Marsicano & Scott, 2013).

Cloze Reading. Students are required to respond in unison to fill in the blanks in a reading passage. The teacher reads a selection, pauses, and the students fill in the missing word or phrase (Raymond, 1988). There is evidence for cloze reading as a technique for improving learning, increasing recall of information, and enhancing reading comprehension (McGee, 1981).

Numbered Heads. This strategy uses a random method for asking students to respond to teacher questions. Students are divided into small groups, and the students count off. Then the teacher poses a problem or asks a question, the group reviews and discusses the task, and the teacher calls a number. The student with the drawn number in each group is asked to explain the group’s response. Numbered heads increases engagement and student responding. The technique helps improve academic performance and the collaborative skills needed to work as part of a team (Kagan & Kagan, 2009).

Inside-Outside Circle. The students form two equal circles: Half of the group stands in a circle facing outward and the other half faces inward. The teacher provides each student with an index card with questions pertinent to the assignment. On a signal from the instructor, the inside circle partner asks a question and the outside circle partner responds. Then the outside circle partner asks a question and inside circle partner responds. The partners exchange cards and the outer circle rotates so that each student has a new partner. The technique helps students develop communication skills as they share ideas (Bennett & Rolheiser, 2001).

Paired Verbal Fluency. Students are paired and each partner is assigned the letter A or B. The partners are asked to engage in a brief, focused conversation in response to a question or topic. Then the teacher prompts partner A to begin talking about the assignment. When the allotted time is up, the teacher signals for student B to begin talking without repeating what his or her partner said. The cycle is repeated for a total of three rounds with each round shorter than the previous round (e.g., 45 seconds, 30 seconds, 20 seconds). This strategy works to improve information processing and verbal fluency (Pearce, 2011; Susanti, 2012).

Round Table. Students work in small groups, and the teacher assigns each student a specific role in the group. The roles rotate over time, allowing each student the opportunity to practice different skills. The assignment commences with the teacher prompting students to provide oral or written responses (Harms & Myers, 2013). The activity shapes fluency as students practice organizing their thoughts and presenting information in front of a group. This strategy allow both peers and teacher to provide feedback (Pearce, 2011).

Timed Partner Reading. This strategy gives students opportunities to improve reading comprehension and text-based discussion skills. The teacher assigns each student a partner, then describes the assignment and allocates time for reading. When prompted, one partner begins reading and the other listens, records positive comments, and notes errors. When time runs out, the listening student exchanges notes with the reader. The cycle continues as the partners switch roles (Giovacchini, 2017).

Active Student Responding Versus Whole Class Lecture

Whole group instruction is the most common method for delivering instruction across all grades (Hollo & Hirn, 2015). The most widely used form of whole class instruction is lecturing (Behr, 1988; Gibbons, Villafañe, Stains, Murphy, & Raker, 2018; Goffe & Kauper, 2014). Lectures have been the favored method of instruction since at least the middle ages (Haskins, 2017). The technique is simple, straightforward, and easy to implement: The teacher talks and the students are responsible for learning (Heward, 2004). It provides teachers with great control of the material to be presented (Friesen, 2008). Generally, along with talking to students, the instructor asks a limited number of questions to selected students to ascertain if the students are paying attention or have acquired the intended knowledge. Lectures are generally followed by summative assessment in the form of a quiz or an exam, or having the students write a paper (Heward & Wood, 2015).

Despite being ubiquitous, lecturing falls far short of being the most effective method of instruction. A primary deficit of didactic presentation is thatlistening is a passive experience (Cleaver et al., 2018). It has been found wanting as a technique for mastering skills (Heward & Wood, 2015). Research suggests that active participation, when combined with teacher feedback, is a much more effective way to boost student performance (Freeman et al., 2014; Pratton & Hales, 1986).Allowing only a few students to respond to questions does not offer sufficient opportunities for all students to actively participate and is not a replacement for increasing engagement and the ongoing progress monitoring afforded by ASR.

A more effective way to maximize learning is for teachers to couple a lecture with a demonstration of the skills being taught, followed by student practice, teacher feedback and, when possible, individual coaching (Joyce & Showers, 2002). In combination, these techniques are superior to didactic lecturing. More important, ASR is a reliable tool that puts the responsibility for ensuring that all students are actively engaged in learning and progressing through a lesson squarely in the hands of the teacher.

How Do Educators Know If Students Are Actively Engaged?

Research supports student engagement as a key measure of instruction. It is important to examine the most common ways in which engagement is employed to see which of these methods produces the most accurate and useful data(Ellis et al., 1994; Freeman, et al., 2014; Greenwood, Horton, & Utley, 2002).

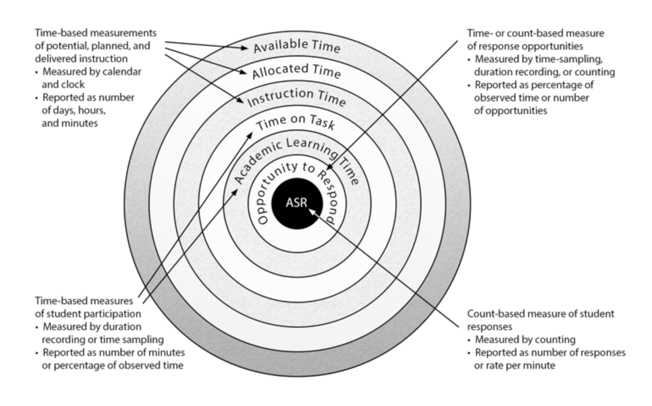

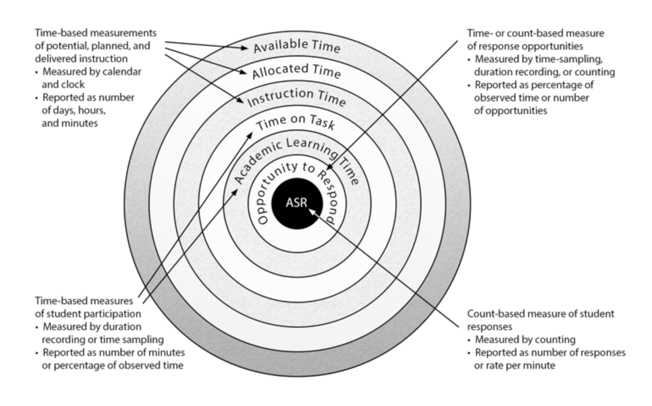

- Time-based measures of instruction. A 1984 study (Berliner) calculated that only about 40% of class time was allocated to actual instruction. It is certainly true that the amount of instructional time is relevant to learning (Hattie, 2009; Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1990). Teachers who provide little time for instruction will likely find the performance of their students lagging behind that of students who have more opportunities to be engaged in lessons. Measures taken to increase the time spent in learning include expanding the number of hours in the school day, lengthening the school year, and allocating more time for instruction each day. Research suggests that merely increasing the amount of potential engagement by increasing instructional time has a minimum impact on achievement (Patall, Cooper, & Allen, 2010; States, Detrich, & Keyworth, 2013). A serious flaw of time-based measures (available time, allocated time, or instructional time) is they are an indirect measure of engagement and cannot tell teachers how frequently students are actively participating in learning.

- Time-based measures of student participation.Two common ways to measure student participation are student time on task and academic instructional time. Although on-task data is easy to collect, research suggests that it correlates poorly with academic performance. A study using time samples of on-task behavior found that students were engaged in an academic activity only approximately 50% of the time (Yair, 2000). These measures, either duration of time on task or time samples, cannot provide teachers with accurate or valid data on whether students are truly participating in learning. These procedures are not designed to measure the actual time a student is engaged; they are capable only of measuring potential time of engagement. Students might appear to be engaged in learning when they are actually thinking of something else or daydreaming.

- Time- or count-based measures of opportunities to respond (OTR).As a method of measuring responses, OTR is an improvement over the first two measures as it focuses on student responding. However, it fails to deliver the critical information teachers require: how often each student actively responds during the lesson. Having an opportunity to respond is not the same as actual responding. In effect, OTR is a measure of the teacher’s behavior rather than a measure of student behavior.

- Count-based measures of student responses.This is the best option for ensuring students are actively engaged in a lesson (Heward & Wood, 2015). Measuring actual student responses through ASR offers teachers a reliable way to identify the frequency of each student’s responses or the rate of student responding during a lesson (Heward, 2013). Another advantage of ASR is its relative ease of implementation (Tincani & Twyman, 2016). A teacher can simply note the number of responses or have the students collect data on their own active responses.

Figure 3 illustrates the different ways of measuring student participation.

Figure 3. ASR compared with other commonly used measures of instructional delivery and student participation (Heward, 1984)

Is Active Student Responding Right for All Students?

A substantial body of research supports ASR and its positive impact on student achievement, but this is not the only consideration for policymakers and practitioners. Educators must also know how versatile, applicable, practical, and cost-effective a practice is for meeting the needs of the students in a given school. Educators should address these questions:

- Is ASR effective for use with different populations (general education, special education, range of ages, varying socioeconomic statuses, differing cultural backgrounds)?

- What curricula and subjects are well suited for use with ASR?

- What formats of instruction can be adapted for use with ASR?

- Can ASR be used for different stages of learning?

- In what settings has ASR been shown to have produced optimum results?

- How difficult is it to train teachers in ASR?

- Is ASR a cost-effective way to increase student engagement?

- IS ASR a good match for the culture of the school?

The extent of how, where, and when ASR practices can be used is large. ASR has great flexibility and is easily adapted for use in multiple settings, but what does the data tell us?

Populations. ASR is employed across a wide range of student populations. It is used for teaching high achievers, average performers, and students with special needs (Boyle & Forchelli, 2014; Cakiroglu, 2014; Christie & Schuster, 2003; Swanson et al., 2014). ASR has been used effectively to increase engagement in diverse age groups beginning with preschoolers and has proven effective for students in all grades through college (Haydon, Mancil, Kroeger, McLeskey, & Lin, 2011). ASR strategies are used with small groups as well as in whole class lessons (Christie & Schuster, 2003; Swanson et al., 2014). Finally, ASR is effective across the spectrum of socioeconomic populations as well as being adaptable for use with students of varying races and cultures (Cartledge & Kourea, 2008; Stanley & Greenwood, 1983).

Curricula and Subjects. The effectiveness of new curricula is maximized by coupling with ASR, which acts as an independent but complementary practice (Lambert, Cartledge, Heward, & Lo, 2006). ASR has also been integrated into highly effective curricula packages including direct instruction and Headsprout Early Reading (Hattie, 2009; Heward & Wood, 2015; Layng, Twyman, & Stikeleather, 2003). Research supports the positive impact of ASR in science, reading, and mathematics (Chard & Kame’enui, 2000; Codding, Burns, & Lukito, 2011; Cooke, Galloway, Kretlow, & Helf, 2011; Cuvo et al., 1995; Drevno, Kimball, Possi, Heward, & Gardner, 1994). ASR maximizes engagement in the following instructional areas: words read, sentences written, mathematics problems solved, lengths and weights measured, musical notes played, historical events identified, and chemical compounds analyzed (Heward & Wood, 2015). Additionally, ASR has been found to be an effective tool when teachers transition and integrate students with disabilities into the general curriculum (Tincani & Twyman, 2016).

Instructional Formats. ASR can be adapted for use across a wide range of formats. It works well with whole class instruction (Maheady, Michielli- Pendl, Mallette, & Harper, 2002; Narayan, Heward, Gardner, Courson, & Omness, 1990); small-group instruction (Tincani & Crozier, 2008); peer tutoring (Arreaga-Mayer, 1998;Bowman-Perrott, 2009; Maheady, Mallette, & Harper, 2006); computer-assisted instruction (Tudor, 1995; Tudor & Bostow, 1991); individualized instruction (Heward & Wood, 2015); and self-study (Heward & Wood, 2015).

Stages of Instruction. ASR can be used in all phases of instruction including acquisition, practice upon acquisition, development of fluency, and application in real-world settings, and it is also effective in generalizing knowledge or skills to novel situations (Heward & Wood, 2015).

Settings. ASR is readily applied in multiple settings including academic classroom, science lab, music room, and gymnasium, as well as community-based settings. Griffin & Ryan, 2016).

Cost-Benefit. ASR offers educators an array of low-cost, high-impact strategies directly associated with improvements in student achievement and reduced misbehavior. Key areas of costs to consider when adopting new practices include commercial package fees, expenditures for equipment required for implementation, professional development expenses, and ongoing maintenance expenditures. A major benefit of ASR is its low cost. The return on investment (ROI) for implementation of ASR techniques is relatively high when compared with structural interventions such as charter schools, school vouchers, class-size reduction, high-stakes testing, and increased spending (States, Detrich, & Keyworth, 2012). Most of ASR’s written, action, and oral response systems are economical, require only small adjustments by the teacher to current instruction practices and curriculum, have the advantage of being low-tech, and require only paper and pencil (see list of active response strategies).

Professional Development. A relatively simple concept that has been around for decades and actively engages students in instruction, ASR is also a set of strategies teachers find easy to master (Haydon et al., 2010; Kretlow, Wood, & Cooke, 2011). Heward has spent more than 30 years researching ASR and has developed an assortment of materials to assist schools in training teachers in the use of these strategies. His training aids include articles on ASR, manuals on how to implement strategies, and video demonstrations (Heward, 2013; Heward, Courson, & Narayan, 1989).Training benefits by being constructed around proven explicit instruction methods such as the “I do, we do, you do” model, which promotes learner mastery and independence through elements such as guided practice and independent practice (Fisher, 2008; Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001). Schools can maximize the impact of ASR strategies by offering follow-up coaching and performance monitoring to ensure newly trained skills are actually used in the classroom (Biancarosa, Bryk, & Dexter, 2010; Kretlow & Bartholomew, 2010; Joyce & Showers 2002).

Compatibility. As an education practice, ASR has great versatility and is compatible with most curricula. ASR strategies can be implemented systemwide or at the classroom level (Tincani & Twyman, 2016). In a classroom, ASR strategies can be fitted for use across a teacher’s schedule or implemented for specific subjects or projects. ASR has been shown to be adaptable to the teacher’s available time and current practices (Heward & Wood, 2015).

The great challenge confronting the wider use of ASR isn’t compatibility across curricula, settings, and populations, but rather will teachers and administrators embrace the practice? Is the new practice compatible with the current values and beliefs of educators? Studies support the theory that a practice must fit within the culture and practices espoused by the school’s leadership and teachers for it to have the greatest likelihood of being adopted and sustained (Fixsen et al., 2005).When a new practice runs counter to these values, resistance is more likely, limiting successful adoption (Heward, 2003). Opposition to increased use of ASR often comes from a segment of the education community that characterizes such practices as “drill and kill.” This resistance stems from concerns that ASR hinders creativity and increases student boredom (Morgan, 2018). Countering these concerns, research shows that systematic drill, repetition, practice, and review produce large effect sizes on achievement (Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006; Dixon & Carnine, 1994).

Why Are Drill and Practice Important in Learning?

Only with fluency does the newly acquired knowledge or skill truly become a part of the student’s repertoire. More important, fluency allows students time to focus on the task at hand and not be distracted by having to think about how to perform the skill (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974). When the new skill becomes automatic, students are free to make creative connections between the goal to be accomplished and how they want to employ the skills in their repertoire (Willingham, 2004). For example, it is impossible to complete a creative writing assignment effectively without having first learned the language, mastered the basic skills of decoding and comprehension, and grasped the skills required for writing words and sentences. Without first achieving competency in the core skills of a task, a student will likely struggle with being a creative writer (Chance, 2008; Willingham, 2009).

Why Being Right Isn’t Enough to Persuade Teachers a Practice is Worthwhile

ASR falls into the category of instruction called explicit instruction. Research strongly supports explicit instruction as the most powerful model of pedagogy (Hattie, 2009). Still, a large portion of the teaching profession continues to question the model, whichrequires teachers to take responsibility for learning, motivating students, directing instruction, and adjusting instruction to meet the educational needs all the students in the classroom. The model embraces an approach that looks to the teacher as the activator of instruction (Grace, 1955; Hattie, 2009; Schug, 2003). It assumes the teacher is the professional trained to identify what students need to be successful, because it is the teacher who has mastered the most effective practices for delivering instruction and is best qualified to diagnose and adapt lessons for students who are struggling.

Despite the strength of the available research supporting explicit instruction, many skeptics question the efficacy of its practices such as ASR. Given the need for buy-in from teachers if a practice is to be successfully adopted, it is important to understand these concerns and to develop plans to address them. Challenges are inevitable and real, and must be overcome for ASR to be embraced by teachers and sustained over time. Only when effective implementation plans are deployed can ASR impact student performance and raise academic performance on NAEP and PISA tests, where scores have been stubbornly flat for decades. Effective strategies for implementing new practices are available and can improve student performance and reverse the real problem of most school initiatives being abandoned within 18 months of adoption (Latham, 1988). For resources on strategies for effective adoption and implementation of new practices, refer to the National Implementation Research Network(NIRN) and Positive Behavior Interventions and Support(PBIS).

Summary

The fact that teacher preparation programs often omit ASR leaves teachers underprepared to meet the challenges they will face in the classroom. When teachers are not aware of ASR’s potential to enhance learning, everyone suffers. It means teachers are likely to be suspicious of the unfamiliar and less inclined to embrace the novel practice, seeing it as inconsistent with what their mentors taught them. Getting teachers to adopt and use ASR strategies every day requires an implementation plan designed to address teacher concerns and overcome hurdles commonly encountered when ASR or other innovative practices are introduced into the school.Citations

Citations

Armendariz, F., & Umbreit, J. (1999). Using active responding to reduce disruptive behavior in a general education classroom. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1(3), 152–158.

Arreaga-Mayer, C. (1998). Increasing active student responding and improving academic performance through classwide peer tutoring. Intervention in School and Clinic, 34(2), 89–94.

Behr, A. L. (1988). Exploring the lecture method: An empirical study. Studies in Higher Education, 13(2), 189–200.

Bennett, B., & Rolheiser, C. (2001). Beyond Monet: The artful science of instructional integration.Toronto, ON: Bookation.

Berliner, D. C. (1984). The half-full glass: A review of research on teaching. In P. L. Hosford (Ed.), Using what we know about teaching(pp. 51–77). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Biancarosa, G., Bryk, A. S., & Dexter, E. R. (2010). Assessing the value-added effects of literary collaborative professional development on student learning. The Elementary School Journal, 111(1), 7–34.

Boyle, J. R., & Forchelli, G. A. (2014). Differences in the note-taking skills of students with high achievement, average achievement, and learning disabilities.Learning and Individual Differences, 35, 9–14.

Bowman-Perrott, L. (2009). Classwide peer tutoring: An effective strategy for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(5), 259–267.

Cakiroglu, O. (2014). Effects of preprinted response cards on rates of academic response, opportunities to respond, and correct academic responses of students with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 39(1), 73–85.

Cartledge, G., & Kourea, L. (2008). Culturally responsive classrooms for culturally diverse students with and at risk for disabilities. Exceptional Children, 74(3), 351–371.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380.

Chance, P. (2008). The teacher’s craft: The ten essential skills of effective teaching.Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Chard, D. J., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2000). Struggling first-grade readers: The frequency and progress of their reading. Journal of Special Education, 34(1),28–38.

Christie, C. A., & Schuster, J. W. (2003). The effects of using response cards on student participation, academic achievement, and on-task behavior during whole-class, math instruction. Journal of Behavioral Education, 12(3), 147–165.

Cleaver, S., Detrich, R. & States, J. (2019). Overview of Performance Feedback. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. Retrieved from https://www.winginstitute.org/teacher-evaluation-feedback

Codding, R. S., Burns, M. K., & Lukito, G. (2011). Meta-analysis of mathematic basic-fact fluency interventions: A component analysis. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 26(1), 36–47.

Cooke, N. L., Galloway, T. W., Kretlow, A. G., & Helf, S. (2011). Impact of the script in a supplemental reading program on instructional opportunities for student practice of specified skills. Journal of Special Education, 45(1), 28–42.

Cuvo, A. J., Ashley, K. M., Marso, K. J., Bingju, L. Z, & Fry, T. A. (1995). Effect of response practice variables on learning spelling and sight vocabulary. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28,155–173.

Dixon, R., & Carnine, D. (1994). Ideologies, practices, and their implications for special education. Journal of Special Education, 28(3), 356–367.

Donovan, J. J., & Radosevich, D. J. (1999). A meta-analytic review of the distribution of practice effect: Now you see it, now you don't. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(5), 795–805.

Drevno, G. E., Kimball, J. W., Possi, M. K., Heward, W. L., Gardner R. III, & Barbetta, P. M. (1994). Effects of active student response during error correction on the acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of science vocabulary by elementary students: a systematic replication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(1), 179–180.

Ebbinghaus, H. (2013). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of Neurosciences, 20(4), 155–156.

Ellis, E. S., Worthington, L. A., & Larkin, M. J. (1994). Effective teaching principles and the design of quality tools for educators. Unpublished paper commissioned by the Center for Advancing the Quality of Technology, Media, and Materials, University of Oregon.

Fisher, D. (2008). Effective use of the gradual release of responsibility model. Author Monographs, 1–4.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature.Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415.

Friesen, S. (2008). Effective teaching practices: A framework and rubric. What did you do in school today?Toronto, ON: Canadian Education Association.

Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (1986). Effects of systematic formative evaluation: A meta-analysis. Exceptional children, 53(3), 199–208.

Gibbons, R. E., Villafañe, S. M., Stains, M., Murphy, K. L., & Raker, J. R. (2018). Beliefs about learning and enacted instructional practices: An investigation in postsecondary chemistry education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 55(8), 1111–1133.

Giovacchini, M. (2017). Timed partner reading and text discussion. English Teaching Forum, 55(1), 36–39.

Godfrey, S. A., Grisham-Brown, J., Schuster, J. W., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2003). The effects of three techniques on student participation with preschool children with attending problems. Education and Treatment of Children, 26(3), 255–272.

Goffe, W. L., & Kauper, D. (2014). A survey of principles instructors: Why lecture prevails. Journal of Economic Education, 45(4), 360–375.

Grace, H. A. (1955). A teacher‐centered theory for education. Peabody Journal of Education, 32(5), 273–281.

Greenwood, C. R., Horton, B. T., & Utley, C. A. (2002). Academic engagement: Current perspectives on research and practice. School Psychology Review, 31(3), 328–349.

Griffin, C. and Ryan, M. (2016). Active Student Responding: Supporting Student Learning and Engagement. Retrieved from https://www.into.ie/ROI/Publications/InTouch/FullLengthArticles/Fulllengtharticles2016/ActiveStudentResponding_InTouchMay2016.pdf

Haller, E. P., Child, D. A., & Walberg, H. J. (1988). Can comprehension be taught? A quantitative synthesis of “metacognitive” studies. Educational researcher, 17(9), 5-8.

Harms, E., & Myers, C. (2013). Empowering students through speaking round tables. Language Education in Asia, 4(1), 39–59.

Haskins, C. H. (2017). The rise of universities. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hattie, J. A. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of 800+ meta-analyses on achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Haydon, T., Conroy, M. A., Scott, T. M., Sindelar, P. T., Barber, B. R., & Orlando, A. (2010). A comparison of three types of opportunities to respond on student academic and social behaviors. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(1), 27–40.

Haydon, T., Mancil, G. R., Kroeger, S. D., McLeskey, J., & Lin, W. Y. J. (2011). A review of the effectiveness of guided notes for students who struggle learning academic content. Preventing School Failure, 55(4), 226–231.

Haydon, T., Marsicano, R., & Scott, T. M. (2013). A comparison of choral and individual responding: A review of the literature. Preventing School Failure, 57(4), 181–188.

Heward, W. L. (1994). Three” low-tech” strategies for increasing the frequency of active student response during group instruction. In R. Gardner III et al. (Eds.), Behavior analysis in education: Focus on measurably superior instruction(pp. 283–320). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Heward, W. L. (2003). Ten faulty notions about teaching and learning that hinder the effectiveness of special education. Journal of Special Education, 36(4), 186–205.

Heward, W. L. (2004). Want to improve the effectiveness of your lectures? Try guided notes.Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Academy of Teaching. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1811/34578

Heward. W. L. (2013). Exceptional children: An introduction to special education(10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Heward, W. L., Courson, F. H., & Narayan, J. S. (1989). Using choral responding to increase active student response. Teaching Exceptional Children, 21(3), 72–75.

Heward, W. L. & Wood, C. L. (2015). Improving educational outcomes in America: Can a low-tech, generic teaching practice make a difference. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. Retrieved from https://www.winginstitute.org/uploads/docs/2013WingSummitWH.pdf

Hollo, A., & Hirn, R. G. (2015). Teacher and student behaviors in the contexts of grade-level and instructional grouping. Preventing School Failure, 59(1), 30–39.

Jerome, A., & Barbetta, P. M. (2005). The effect of active student responding during computer-assisted instruction on social studies learning by students with learning disabilities. Journal of Special Education Technology, 20(3), 13–23.

Joyce, B. R., and B. Showers (2002). Student achievement through staff development(3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Kagan, S., & Kagan, M. (2009). Kagan cooperative learning.San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological bulletin, 119(2), 254.

Konrad, M., Joseph, L. M., & Itoi, M. (2011). Using guided notes to enhance instruction for all students. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46(3), 131–140.

Kothiyal, A., Majumdar, R., Murthy, S., & Iyer, S. (2013). Effect of think-pair-share in a large CS1 class: 83% sustained engagement. Proceedings of the Ninth Annual International ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research,137–144.

Kretlow, A. G., & Bartholomew, C. C. (2010). Using coaching to improve the fidelity of evidence-based practices: A review of studies. Teacher Education and Special Education, 33(4), 279–299.

Kretlow, A. G., Wood, C. L., & Cooke, N. L. (2011). Using in-service and coaching to increase kindergarten teachers’ accurate delivery of group instructional units.Journal of Special Education, 44(4), 234–246.

Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. A. (2003). Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 3–21.

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6(2), 293–323.

Lambert, M. C., Cartledge, G., Heward, W. L., & Lo, Y. Y. (2006). Effects of response cards on disruptive behavior and academic responding during math lessons by fourth-grade urban students. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(2), 88–99.

Latham, G. (1988). The birth and death cycles of educational innovations. Principal, 68(1), 41–43.

Layng, T. J., Twyman, J. S., & Stikeleather, G. (2003). Headsprout Early Reading: Reliably teaching children to read. Behavioral Technology Today, 3, 7–20.

Lysakowski, R. S., & Walberg, H. J. (1982). Instructional effects of cues, participation, and corrective feedback: A quantitative synthesis. American Educational Research Journal, 19(4), 559-572.

Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Oswald, F. L. (2018). Corrigendum: Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1202–1204.

Maheady, L., Mallette, B., & Harper, G. F. (2006). Four classwide peer tutoring models: Similarities, differences, and implications for research and practice. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 22(1), 65–89.

Maheady, L., Michielli-Pendl, J., Mallette, B., & Harper, G. F. (2002). A collaborative research project to improve the academic performance of a diverse sixth grade science class. Teacher Education and Special Education, 25(1), 55–70.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement.Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

McGee, L. M. (1981). Effects of the cloze procedure on good and poor readers’ comprehension. Journal of Reading Behavior, 13(2), 145–156.

Morgan, P. L. (2018). Should U.S. students do more math practice and drilling? Psychology Today.Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/children-who-struggle/201808/should-us-students-do-more-math-practice-and-drilling

Narayan, J. S., Heward, W. L., Gardner R. III, Courson, F. H., & Omness, C. K. (1990). Using response cards to increase student participation in an elementary classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(4), 483–490.

Nation’s Report Card. (2017). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Educational Statistics. Retrieved from the NAEP Data Explorerhttp://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata/

Nuthall, G. (2005). The cultural myths and realities of classroom teaching and learning: A personal journey. Teachers College Record, 107(5), 895–934.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., and Allen, A. B. (2010). Extending the school day or school year: A systematic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 80(3):401–436.

Pearce, A. R. (2011). Active student response strategies. CDE Facilities Seminar. Retrieved from

http://www.cde.state.co.us/sites/default/files/documents/facilityschools/download/pdf/edmeetings_04apr2011_asrstrategies.pdf

Pratton, J., & Hales, L. W. (1986). The effects of active participation on student learning. Journal of Educational Research, 79(4), 210–215.

Programme for International Student Assessment. (2015). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/

Raymond, P. (1988). Cloze procedure in the teaching of reading. TESL Canada Journal, 6(1), 91–97.

Reber, R., Fazendeiro, T. A., & Winkielman, P. (2002). Processing fluency as the source of experiences at the fringe of consciousness. Psyche, 8(10), 175–188.

Schug, M. C. (2003). Teacher-centered instruction: The Rodney Dangerfield of social studies. In J. Leming, L. Ellington, & K. Porter-Magee (Eds.), Where did social studies go wrong?(pp. 94–110). Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Foundation.

Simon, C. A. (2019). National Council of Teachers of English. Using the think-pair-share technique. Retrieved from http://www.readwritethink.org/professional-development/strategy-guides/using-think-pair-share-30626.html

Slavin, R. (2019). Replication. [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://robertslavinsblog.wordpress.com/2019/01/24/replication/

Smith, A. M., Floerke, V. A., & Thomas, A. K. (2016). Retrieval practice protects memory against acute stress. Science, 354(6315), 1046–1048.

Stanley, S. O., & Greenwood, C. R. (1983). How much “opportunity to respond” does the minority disadvantaged student receive in school? Exceptional Children, 49,370–373.

States, J., Detrich, R. & Keyworth, R. (2012). How does class size reduction measure up to other common educational interventions in a cost-benefit analysis? Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/how-does-class-size

States, J., Detrich, R. & Keyworth, R. (2013). Does a longer school year or longer school day improve student achievement scores? Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute.https://www.winginstitute.org/does-longer-school-year

Stichter, J. P., Lewis, T. J., Whittaker, T. A., Richter, M., Johnson, N. W., & Trussell, R. P. (2009). Assessing teacher use of opportunities to respond and effective classroom management strategies: Comparisons among high- and low-risk elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(2), 68–81.

Susanti, R. (2012). Teaching listening through paired verbal fluency strategy for senior high school students. E-jurnal mahasiswa prodi pend bahasa inggris 2012, 1(4).

Swanson, E., Hairrell, A., Kent, S., Ciullo, S., Wanzek, J. A., & Vaughn, S. (2014). A synthesis and meta-analysis of reading interventions using social studies content for students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(2), 178–195.

Swanson, H. L., & Hoskyn, M. (2001). Instructing adolescents with learning disabilities: A component and composite analysis. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 16(2), 109–119.

Tenenbaum, G., & Goldring, E. (1989). A meta-analysis of the effect of enhanced instruction: Cues, participation, reinforcement and feedback and correctives on motor skill learning. Journal of Research & Development in Education.

Tincani, M. (2011). Preventing challenging behavior in your classroom: Positive behavior support and effective classroom management.Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Tincani, M., & Crozier, S. (2007). Comparing brief and extended wait-time during small group instruction for children with challenging behavior. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16(4), 355–367.

Tincani, M., & Twyman, J. S. (2016). Enhancing engagement through active student response. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University, Center on Innovations in Learning.

Tudor, R. M. (1995). Isolating the effects of active responding in computer‐based instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(3), 343–344.

Tudor, R. M., & Bostow, D. E. (1991). Computer‐programmed instruction: The relation of required interaction to practical application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(2), 361–368.

United States. National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform: A report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education, United States Department of Education. The Commission.

Walberg, H. J. (1999). Productive teaching. New directions for teaching practice and research, 75-104.

Wang, M. C., Haertel, G. D., & Walberg, H. J. (1990). What influences learning? A content analysis of review literature. Journal of Educational Research, 84(1), 30–43

Willingham, D. T. (2004). Practice makes perfect—but only if you practice beyond the point of perfection.Retrieved from https://www.aft.org/periodical/american-educator/spring-2004/ask-cognitive-scientist

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don't students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wood, C. L., Mabry, L. E., Kretlow, A. G., Lo, Y., & Galloway, T. W. (2009). Effects of preprinted response cards on students’ participation and off-task behavior in a rural kindergarten classroom. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 28(2), 39–47.

Yair, G. (2000). Educational battlefields in America: The tug-of-war over students' engagement with instruction. Sociology of Education, 73(4), 247–269.