Principal Retention Overview

Principal Retention PDF

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2020). Principal Retention Overview. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-leadership-principal-retention.

Principals exert a strong influence on student learning and achievement through their ability to impact the organizational school features necessary for high-quality teaching and learning (Hitt & Tucker, 2016; Leithwood, Harris, & Hopkins, 2019; Leithwood, Harris, & Strauss, 2010; Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008; Supovitz, Sirinides, & May, 2010). While their impact on student achievement is indirect, principals exert influence over factors such as school climate and teacher working conditions, and make human capital (i.e., teacher hiring) and professional development decisions that indirectly influence student learning outcomes (Cannata et al., 2017; Sebastian & Allensworth, 2012). Not surprisingly, principal leadership is highly predictive of teachers’ perceptions of their working environment and their decision to remain in their schools from year to year (Boyd et al., 2011; Burkhauser, 2017; Grissom, 2011; Kraft, Marinell, & Yee, 2016; Ladd, 2011; Redding, Booker, Smith, & Desimone, 2019).

Stability in the principalship is critical, particularly for schools in need of rapid improvement, where consistent leadership across many years is necessary for initiatives to take root and positively impact student outcomes (Edwards, Quinn, Fuller, & Pendola, 2018; Pendola & Fuller, 2018). Unfortunately, these schools are more likely to deal with high levels of principal turnover (Gates et al., 2006; Papa, 2007), resulting in the hiring of less qualified replacements who then leave for lower need schools after gaining experience, contributing to a continuous cycle of high turnover and low student achievement (Branch, Hanushek, & Rivkin, 2012; Fuller & Young, 2009; Miller, 2013).

This report documents broadly the research that addresses the prevalence of principal turnover, the factors associated with a principal’s decision to leave, the consequences of principal turnover for teaching and learning, and evidence-based strategies for improving principal retention.

The Problem of Principal Turnover

Principals assume responsibilities and pressures that include improving student learning, managing staff, allocating school resources, cultivating a positive school climate, and rallying stakeholders around improvement goals (Hallinger, Wang, & Chen, 2013); often, the benefits of the job are not adequate to compensate for the increased stress and overwhelming workload, resulting in principal turnover (Pijanowski & Brady, 2009). Researchers addressing principal turnover have defined it in multiple ways depending on the research question of interest, which has made interpretations of data and summarizing the literature challenging (Rangel, 2018).

Various studies have defined turnover as mobility or a single departure from a school (e.g., Horng, Kalogrides, & Loeb, 2010), as intention to leave rather than actual departure (e.g., Tekleselassie & Villarreal, 2011), or as length of tenure or retention at a school (e.g., Fuller & Young, 2009; Papa, 2007), or have included assistant principals or district leaders together with principals to determine levels of “administrator” turnover (Lochmiller, Adachi, Chesnut, & Johnson, 2016). The simplest definition of principal turnover, of course, is when a principal does not return to the same school from one year to the next (Rangel, 2018). However, this does not inform the reason for the departure; for example, salary dissatisfaction or voluntary versus involuntary departure (Farley-Ripple, Raffel, & Welch, 2012).

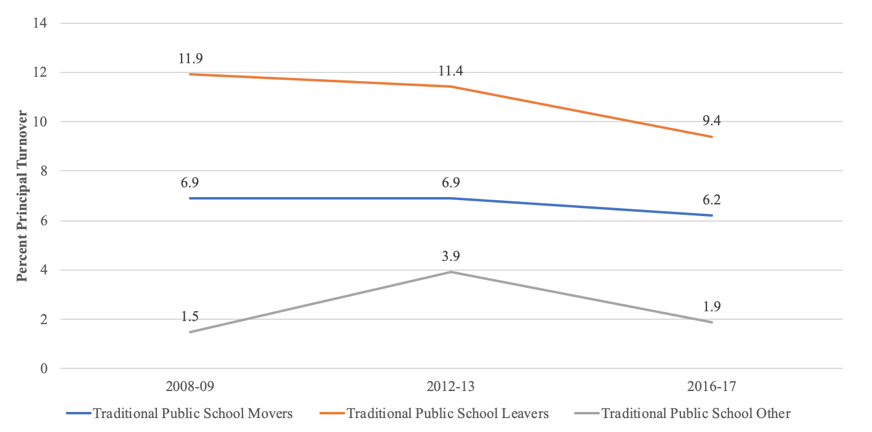

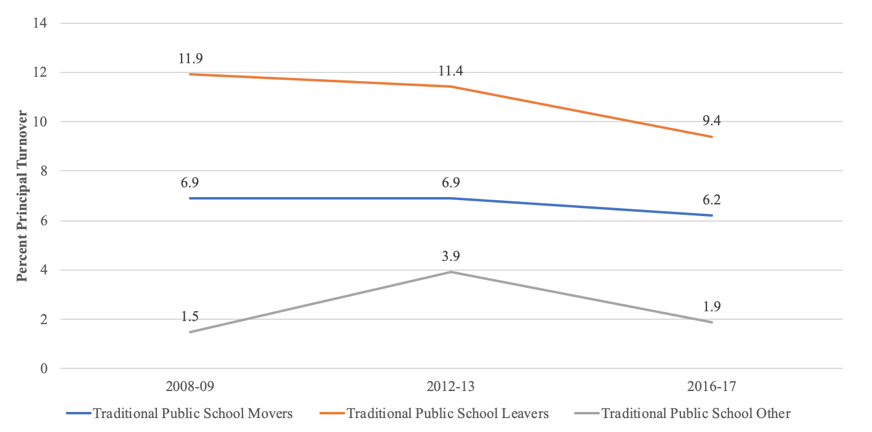

Several nationally representative studies have shown that more than 20% of principals leave public schools each year (Battle, 2010; Cullen & Mazzeo, 2007; DeAngelis & White, 2011), including 12% who leave the principalship altogether (Goldring & Taie, 2014). As of 2016–2017, the national average tenure of principals was 4 years, with approximately one third serving their school for less than 2 years, and only 11% remaining at their school for 10 years or more (Taie & Goldring, 2017). Figures 1 and 2 show the most recent national patterns of principal turnover across time for traditional public, and public charter schools, respectively, in terms of movers (remained as principal but moved to a different school after their base year), and leavers (no longer principal after their base year) (Goldring & Taie, 2018). Figure 1 shows that the overall percentage of turnover (including movers and leavers) for traditional public school principals has hovered around 20% for two of the three years studied, with slightly lower turnover rates in 2016-17 in large part due to a decline in leavers.

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Principal Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2016–2017 Principal Follow-Up Survey” (Goldring & Taie, 2018). Note: “Traditional Public School Other” refers to the percentage of principals from the sample who had left their base-year school but for whom mover or leaver status was unable to be determined.

Figure 1. Percentage of traditional public school principal movers and leavers, 2008–2009 through 2016–2017

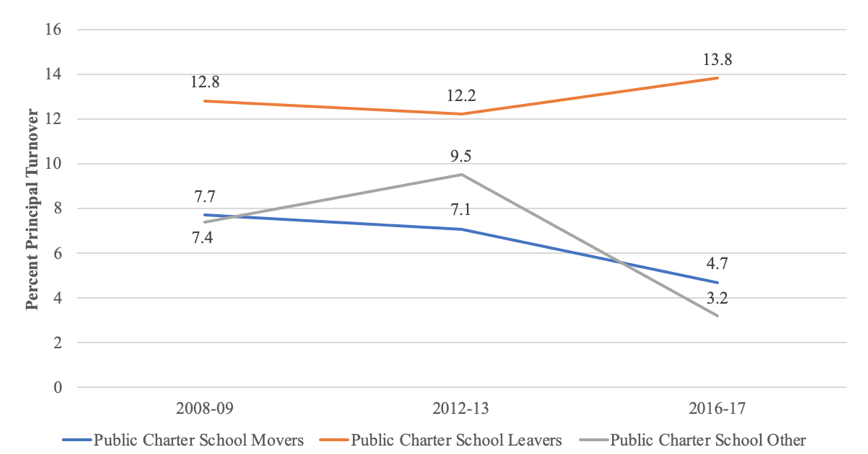

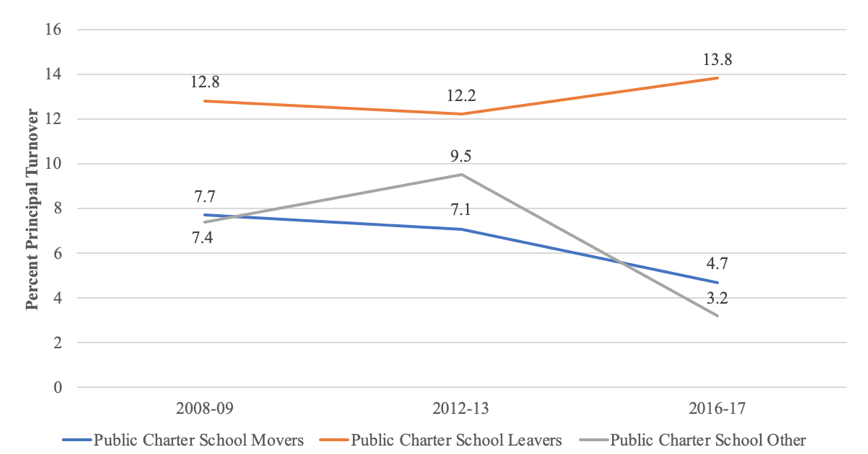

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Principal Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2016–2017 Principal Follow-Up Survey” (Goldring & Taie, 2018). Note: “Public Charter School Other” refers to the percentage of principals from the sample who had left their base-year school but for whom mover or leaver status was unable to be determined.

Figure 2. Percentage of public charter school principal movers and leavers, 2008–2009 through 2016–2017

Figure 2 demonstrates declining rates of mobility among public charter principals across the 3 years, but a slight increase in the percentages leaving the profession; in addition, there was less data available on the destination of public charter versus traditional school principals who exited their schools. Across all 3 school years measured, traditional public school principals were more likely than public charter school principals to remain in their schools. These descriptive data are consistent with other research that documents significantly higher turnover rates for charter public school principals than for traditional public school principals (Battle, 2010; Ni, Sun, & Rorrer, 2015; Sun & Ni, 2016).

A study using Utah administrative data found that an average of 26% of principals exited charter schools annually, a rate significantly higher than that of traditional public school principals, and ranged from 14% to 44% from 2004 to 2010 (Ni et al., 2015); similar results were found for New York City charter schools (New York City Charter School Center, 2012). Sun and Ni (2016) examined nationally representative data to explore which variables may impact the higher turnover rates of charter school principals. Approximately half of the turnover gap between charter public school and traditional public school principals was explained by a combination of principal characteristics, school contexts, principal leadership practices, and working conditions, with working conditions constituting the largest source of the gap. The researchers noted that many of the charter school principals worked under relatively difficult conditions as they were responsible for managing inexperienced staff; on average, 60% were either first-year teachers or new to the school.

When combining charter public school and traditional public school principal groups, the national data show that the rate of leavers has decreased over the time period studied. However, many schools and districts across the country, particularly those with high numbers of disadvantaged students, have reported high turnover and vacancy rates (National Association of Secondary School Principals, 2017; Snyder, de Brey, & Dillow, 2016).

Principals may leave their positions to pursue other opportunities within or outside the school sector, or to retire. In fact, researchers have pointed out that many principals are eligible for retirement within the next few years. For example, Fusarelli, Fusarelli, & Riddick (2018) reported that approximately half of principals in North Carolina’s rural high-poverty schools would be eligible for retirement within 4 years. The shortage of qualified and effective principals is regularly acknowledged and discussed in the field of educational leadership, particularly in light of projections that the demand for principals will grow 6% by 2022 due to increases in population (National Association of Secondary School Principals, 2017). Understanding the factors that influence principal turnover can help schools, districts, and states ensure that retention strategies are carefully designed to appropriately and effectively target improvements to retention within local contexts.

Factors Associated with Principal Turnover

An extensive body of primarily exploratory (noncausal) research has accumulated regarding the factors that may contribute to principal turnover (Rangel, 2018). Researchers have examined relationships between turnover and principal, district, school, and student characteristics; workplace conditions/compensation; accountability policies; and principal effectiveness. Rangel noted the general lack of causal research and inconsistent findings across much of the literature, with results depending in large part on the measure of turnover used and the context of the study, making interpretation and synthesis difficult.

Employing the same national datasets as in the Goldring and Taie (2018) study, Tekleselassie and Choi (2019) examined how variations in principal, school, and district characteristics influenced principal turnover (broken out by movers and leavers) using hierarchical generalized linear modeling procedures, considered to be a strong methodological approach for examining data of this nature (Subedi & Howard, 2013). This statistical approach identified variables with significant relationships to turnover, even when controlling for all other characteristics in the model. Tekleselassie and Choi derived broad sets of factors that predicted principal mobility and departure: principal characteristics, school/student characteristics, workplace conditions/compensation, and district/policy characteristics. Their results are highlighted below as a way of organizing a discussion and synthesis of research that address the factors influencing principal turnover.

Principal Characteristics. Researchers have examined how demographic characteristics such as age, experience, education, gender, and race are related to principal turnover. Tekleselassie and Choi (2019) found that, when controlling for a variety of relevant variables in their model, principal age, experience, and education degree attainment were significantly related to turnover. The odds of principals leaving their position grew with each additional year of age, while with each additional year of experience they became less likely to move or leave. Older principals, of course, are more likely to retire, and as principals accrue experience they may deepen their levels of professional commitment or have fewer opportunities for occupational alternatives, keeping them in their position (Gates et al., 2006).

Effective veteran principals who are stable may bring loyalty and higher levels of expertise and content knowledge to the table, while those who are less effective may remain simply because of few other attractive career options. Newer principals, on the other hand, typically have fewer years of experience than those they are replacing. Given that principals become more effective as they accumulate experience (Clark, Martorell, & Rockoff, 2009; Grissom, Blisset, & Mitani, 2018), replacement of principals may have negative ramifications for effectiveness (Bartanen, Grissom, & Rogers, 2019); see later discussion below.

Tekleselassie and Choi (2019) also found that principals who had earned doctoral degrees were more likely than those with master’s or bachelor’s degrees to move but not leave schools. Similar results have been found in other studies (Lochmiller et al., 2016 Tekleselassie &Villareal, 2011); however, some found lower turnover rates for principals with master’s degrees (Gates et al., 2006; Ni et al., 2015). Principal gender and ethnicity were not related to principal turnover when other variables of relevance were controlled for (Tekleselassie & Choi, 2019). Rangel’s (2018) synthesis concluded that research pertaining to principal ethnicity and gender was generally mixed and inconclusive.

One principal characteristic that has received scant research attention is how a principal’s effectiveness is associated with the likelihood of turnover (Grissom & Bartanen, 2019a, 2019b; Husain, Miller, & Player, 2019). While principal turnover may be detrimental to school performance in the short term (Miller, 2013), longer term principal turnover may ultimately be positive if higher turnover rates occur for lower performing principals (Grissom & Bartanen, 2019a). Grissom and Bartanen used measures of teachers’ perceptions of principal quality, school value-added scores, and principal effectiveness ratings made by supervisors to construct a measure of principal effectiveness in Tennessee, and examined their relationship to different types of principal turnover, such as inter- and intradistrict moves, exits from the education system, and demotions to non-principal positions. On average, less effective principals were more likely to leave their schools, and higher turnover among low-performing principals was primarily driven by exits from the system and demotions to other school positions. An examination of supervisor evaluation ratings also found higher turnover among the highest performing principals, with many of these principals promoted to central office positions.

An analysis of both local data from New York City and national data (Schools and Staffing Survey) similarly found that lower performing principals (based on teacher ratings) were more likely to turn over than those who were rated higher (Husain et al., 2019). The researchers suggested that at least some principal turnover may be positive, if the lower quality principals who vacate are replaced by higher quality principals; however, the question of the extent to which this occurs has yet to be addressed in research.

School/Student Characteristics. Several school characteristics impacted principal turnover, both positively and negatively, in the analysis conducted by Tekleselassie and Choi (2019). Principal turnover was found to increase as the percentage of students of color increased in a school. This finding is consistent with other research suggesting that schools considered to be “hard to staff,” which often include high percentages of disadvantaged students of color and/or limited English-proficient students, are more likely to deal with high levels of principal turnover (Gates et al., 2006; Papa, 2007). For example, Horng et al (2009) found that principals in Miami were 51% more likely to exit schools with large numbers of low-income and Latino and African American students, and Yan (2020) found from a national sample that principals in schools with high concentrations (third and fourth quartile) of students of color were 60% to 70% more likely than principals in schools with the lowest quartile percentage of students of color to move to other schools.

Unfortunately, when younger principals, who are often systematically assigned to these schools (Horng et al., 2009) depart, they typically move to schools with less poverty, meaning that these poorer schools often continue to be staffed by less experienced principals (Béteille, Kalogrides, & Loeb, 2012; Clotfelter, Ladd, Vigdor, & Wheeler, 2006). This frequent administrator turnover can further fuel teacher turnover, which may limit gains and benefits for groups of students for whom stable leadership and teaching are the most crucial (Béteille et al., 2012).

School level, size, and performance were also found to be significant predictors of turnover in Tekleselassie and Choi’s (2019) analysis. Nationally, principals were 3 times more likely to leave combined schools (e.g., schools with merged elementary and middle levels) than elementary schools; significant differences were not observed for other school level comparisons. The researchers noted that principal roles in these schools may be more complex; further inspection of the data revealed that these principals were also paid less than other principals (Taie & Goldring, 2019), which may contribute to their higher propensity for turnover. Principals were less likely to leave larger schools, a finding consistent with other research (Gates et al., 2006; Podgursky, Ehlert, Lindsay, & Wan, 2016; Tekleselassie & Villareal, 2011). Principals at larger schools typically have higher salaries (Taie & Goldring, 2019) and presumably larger administrative staffs, which may help to offset the potentially increased workload and intensity that typically comes with leading a large school (Papa, Lankford, & Wyckoff, 2002).

Tekleselassie and Choi (2019) also found that meeting adequate yearly progress (AYP) reduced the chances of principal turnover by 40%, a finding consistent with other research that suggests that lower academic performance is associated with higher principal turnover rates (Burkhauser, Gates, Hamilton, & Ikemoto, 2012; DeAngelis & White, 2011; Fuller & Young, 2009; Horng et al., 2009). Not surprisingly, accountability policy has also been shown to be associated with principal turnover, with studies showing that principals at schools facing sanctions for poor performance were more likely to relocate to higher performing schools (Clotfelter et al., 2006; DeAngelis & White, 2011; Mitani, 2017).

Workplace Conditions/Compensation. Currently, researchers have not established a common definition for “principal working conditions” (Fuller, Hollingworth, & Young, 2015), although working conditions are more likely to be subject to policy influences than principal or student characteristics, or school contexts (Yan, 2020). Researchers have studied a variety of issues thought to represent working conditions—for example, stress and the emotional aspects of the work, student disciplinary environment, job satisfaction, and compensation—and assessed their relationship to principal turnover. Principals must assume a wide array of duties and face many external pressures (Hallinger et al., 2013), and often any job benefits provided are not sufficient to compensate for high levels of stress and an excessive workload (Pjanowski & Brady, 2009). Principals are more likely to turn over as the number of hours they work rises (Fuller et al., 2015; Tekleselassie & Choi, 2019; Tekleselassie & Villareal, 2011), suggesting that workplace stressors that are not addressed through supportive programming (e.g., active teacher leadership, principal mentoring) can decrease principal stability.

The student disciplinary environment in a school, as reflected by indices such as student suspension/expulsion rates, also influences working conditions and, in turn, retention (Sun & Ni, 2016; Tekleselassie & Villareal, 2011). One study found that as the number of instances of teacher abuse (including physical abuse, verbal abuse, widespread disorder in classrooms, and disrespect by students) increased, the risk of principals leaving schools increased by 23% (Sun & Ni, 2016). Yan (2020) found for every standard deviation improvement in a school’s disciplinary environment rating, the odds of a principal moving to another school declined by 36%. While principals frequently report a desire to work in safer and easier-to-serve schools (Horng et al., 2009), this desire frequently stems from a lack of coherent instructional programs and regular routines, and poor disciplinary environments rather than an aversion to working with certain student populations or school contexts (Yan, 2020).

While states and districts provide principals with administrative and professional supports, they also frequently exert excessive control over issues and functions at the school level, which can harm principal satisfaction and retention (Ni, Yan, & Pounder, 2018). Principals who perceive they have adequate influence over areas such as hiring and evaluating teachers, setting disciplinary policies, and budgeting are less likely to either leave the principalship or move to another school (Tekleselassie & Villareal, 2011). In addition, interviews with principals have revealed that having this autonomy is important in their decision to remain in a school (Farley-Ripple et al., 2012; Oberman, 1996). Yan (2020) found that the specific area of influence was important for principal retention. Increased principal influence over teacher professional development and budgeting, and less influence over setting performance standards were both associated with a lower risk of turnover, suggesting that principals perceive they need more influence over personnel and financial allocation for school improvement but perceive the state’s role in setting student performance standards as noninterfering.

Job satisfaction also is strongly related to principal turnover and, in part, is likely a function of the principal’s working conditions. Tekleselassie and Choi (2019) created a composite measure for satisfaction based on principal responses to questions regarding satisfaction with the district and school, enthusiasm for the job, energy level to continue working as a principal, and view of faculty job satisfaction. Increased principal job satisfaction was found to reduce the likelihood of turnover, a finding consistent with earlier research (Boyce & Bowers, 2016; Tekleselassie & Villareal, 2011). Boyce and Bowers used nationally representative data to examine the role of satisfaction in turnover, and determined two types of principal leavers: those who were satisfied with their position and those who were not. They found that many principals who left had a positive attitude about their job and reported higher levels of influence over areas such as budget and hiring of teachers, but were lured away by “pull factors” in other settings such as promotion opportunities, better salary, and retirement benefits. Disaffected leavers, on the other hand, reported lower efficacy and influence levels and a more negative school climate.

Some evidence suggests that higher principal salaries are associated with lower turnover (Baker, Punswick, & Belt, 2010; Papa, 2007). Somewhat surprisingly, however, every unit increase of principal salary (i.e., $10,000) was associated with increased risk of a principal leaving but not moving, according to the national study by Tekleselassie and Choi (2019), which suggested that salary may serve as a proxy for other attributes such as relevant skill and experience that make the principal desirable and visible for other positions. Salary’s effect on turnover was removed, however, when district policy contexts and characteristics were also controlled for in their model; see further discussion below. Tran and Buckman (2017) similarly found that higher salaries helped explain a principal’s exit to another district but not a move within the current district. Yan (2020) found that, when controlling for principal characteristics and school context, for every unit increase in salary the risk of moving to another school declined by 53%. However, when also controlling for working conditions variables that included job benefits and other nonmonetary working conditions, the significant effect of salary was eliminated, suggesting these factors may serve to moderate the influence of salary on principal turnover, a finding consistent with Tekleselassie and Choi (2019).

District/Policy Characteristics. Districts play an important role in principal retention by providing policies, practices, and resources that encourage principal competence, satisfaction, and efficacy in their roles. Several studies have examined how district policies and job benefits affect principal turnover. Tenure protections have been found to reduce the odds of departure from schools, while union membership has been shown to reduce the odds of moving to a different school (Tekleselassie and Choi, 2019; Yan, 2020). Yan found that principals within tenure systems were two thirds less likely to leave the education system and those with collective bargaining contracts were 56% less likely than those who lacked these job benefits to move to non-principal positions.

District policies designed to enhance teacher working conditions to improve teacher retention may have the additional benefit of improved principal retention. Tekleselassie and Choi (2019) found that districts providing National Board Certification incentives and those providing incentives for teachers working in hard-to-staff locations also benefited from improved principal retention, suggesting a possible reciprocal relationship in which policies that allow principals to maximize teacher retention, in turn, improve principal stability.

Principal Development and Support. The presence and quality of professional development, preparation, and in-school supports also factor into a principal’s likelihood of remaining at a school. Tekleselassie and Villareal (2011) found that access to high-quality preparation programs, internships, and on-the-job mentoring significantly reduced the chances of a principal’s intention to leave a school. One causal study found evidence of reduced principal attrition following a balanced leadership professional development program that provided research-based guidance in the form of 21 key leadership responsibilities, including monitoring instruction and involvement in curriculum and instruction (Jacob, Goddard, Kim, Miller, & Goddard, 2015; Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005). Programs that seek to carefully identify and prepare principals to work in challenging schools, and that also work with districts to further support and develop these principals, are more likely to produce principals who will remain in these schools (Davis, Darling-Hammond, LaPointe, & Meyerson, 2005; Sutcher, Podolsky, & Espinoza, 2017).

The Consequences of Principal Turnover

Principal turnover has the potential to affect student, teacher, and school outcomes negatively by disrupting a school’s organizational climate and culture and the structures that facilitate teachers’ work, all of which are essential for improved instructional processes and student achievement (Robinson et al., 2008; Sebastian & Allensworth, 2012). Disruptive effects may be short term, or endure depending on the capacity of the replacement principal to reestablish or improve the previous school conditions (Henry & Harbatkin, 2019). Turnover’s impact depends on how these negative disruptive effects are balanced with any replacement effects associated with a new principal, who may be more or less effective than the departing principal (Bartanen et al., 2019).

Teacher Turnover. Principals are responsible for human capital management, including processes to strategically hire and retain teachers who are likely to be successful in the school’s context; these management processes may suffer during disruptions (Grissom & Bartanen, 2019b). Indeed, research suggests that higher rates of principal turnover are related to higher teacher turnover rates (Miller, 2013; Ronfeldt, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2013); for example, one study found that the odds of teacher turnover were 10% higher in the year after a principal departed, and that principal turnover was linked to increased chances of the most effective teachers leaving the school (Béteille, et al., 2012). Miller (2013) documented increased turnover of teachers during the year before a principal exited and in the year following the exit, followed by rates that returned to the levels found prior to the principal’s departure.

Henry and Harbatkin (2019) used a methodologically stronger causal analysis model and data from North Carolina to isolate the effect of principal turnover from other factors (e.g., school-level characteristics and trends associated with principal turnover and school outcomes) to get a clearer picture of turnover’s impact. They found a significant increase (approximately 1.7 percentage points) in teacher turnover in the year of the transition to a new principal, with increased turnover continuing for at least 2 additional years past the initial transition.

A recent study of principal turnover in Missouri and Tennessee using a matched comparison group process (schools that lost their principal compared with schools on a similar trajectory that kept their principal for at least 1 more year) to estimate causal effects similarly found a significant decrease in teacher retention following a principal departure, and the negative effects persisted for several years after the principal transition (Bartanen et al., 2019). This study further examined the impact of different types of principal turnover (transfers to other schools, exits from the system, promotions, and demotions) and determined that the negative effects were strongest for principal transfers and demotions, with demotions dramatically increasing the percentage of teachers who were new to the school following the transition.

Presumably, principals demoted were ineffective and likely led teachers who were less effective as well, resulting in higher levels of teacher turnover (potentially mandated by the district or new principal). Improvements to school leadership are strongly associated with reductions in teacher turnover (Kraft et al., 2016), so this finding is not necessarily a negative or permanent one.

Student Achievement. Some research suggests that principal turnover is associated with lower student achievement (Rangel, 2018). When schools have new principals, achievement gains are reduced compared with schools that maintain their principal (Béteille, et al., 2012; Miller, 2013). One descriptive analysis (meaning no causation can be inferred) found that half of schools that experienced a principal transition saw reduced achievement in the first year of the new principal (Burkhauser et al., 2012). Schools, however, are often on a downward performance trajectory in the years leading up to a principal departure (Miller, 2013), suggesting that the decline may drive principal departure, making it difficult to isolate the effect of the principal transition (Bartanen et al., 2019). Miller (2013) observed a rebounding effect in a school’s achievement 1 to 2 years after turnover, and it is difficult to know whether the improvement would have occurred even if the principal had been retained.

Other factors may mediate principal turnover’s contributions to achievement, such as downturns in school performance due to short-term factors beyond the principal’s control (e.g., large numbers of effective teachers retiring). At the high school level, Weinstein, Schwartz, Jacobowitz, Ely, and Landon (2009) studied a sample of schools over a 10-year period and found that graduation rates in New York City schools remained stable after one principal change but increased significantly after two or more changes; however, no impact on graduation rate was observed in a study of schools in North Carolina (Henry & Harbatkin, 2019).

Several empirical studies that control for a range of influential variables involving the impact of principal turnover on student achievement have recently emerged in the literature. Walsh and Dotter (2019) investigated the principal replacement policy in District of Columbia Public Schools and estimated the causal impact of principal turnover by controlling for alternative explanations for a principal departure. They found increased schoolwide achievement (4 percentile points) in schools that replaced their principal after the third year of transition compared with schools that retained their original principal. These findings were similar to a study in the same district that found positive impacts of teacher turnover on student achievement (Adnot, Dee, Katz, & Wycoff, 2017). An important caveat when interpreting these findings is the need for district access to a pool of effective educators to replace those who are ineffective (Levin & Bradley, 2019).

In contrast, several studies that estimated causal effects of principal turnover found declining school achievement in the year following the transition. Significant though modest decreases in student achievement were found following principal turnover in schools in North Carolina (Henry & Harbatkin, 2019) and in Missouri and Tennessee (Bartanen et al., 2019). The Bartanen study found that negative achievement effects were largest for turnover involving principal transfers to other schools or promotions; turnover that involved demotions (of presumably less effective principals) resulted in no impact on achievement in the near term and positive impact in later years. The researchers further concluded that while principal turnover increased teacher turnover, this increase did not explain the decline in achievement. Instead the major driver was principal quality, with replacement principals on average having less experience than their predecessors, at least at the outset of their tenure. In fact, 60% of “new-to-the-school” principals had no prior experience as a principal across the two states.

These studies suggest that not all principal turnover is harmful to school performance and can actually have positive, if longer term, effects on student achievement when less effective principals are replaced with more effective ones. A key issue, however, is the adequacy of the supply of these effective school leaders, particularly for hard-to-staff schools that may struggle with recruitment along with retention (Bartanen et al., 2019). Bartanen and colleagues, noting decreases in student achievement after principal transfers, cautioned against district policies that simply rotate successful principals among schools, but acknowledged that policies that relocate experienced principals into hard-to-staff schools may ultimately result in benefits that outweigh the initial costs.

Principal turnover can be disruptive to school climate, culture (e.g., shared values, norms and contexts), and social resources (e.g., relationships between principals and teachers) (Rangel, 2018). Principal turnover is associated with more negative school culture, defined as “shared values, norms, and contexts” (Mascall & Leithwood, 2010, p. 369). Burkhauser et al.’s (2012) descriptive analysis showed concern among school staff that new principals induced organization instability through the introduction of large numbers of rapid changes to policies and procedures. Bartanen et al.’s (2019) analysis also revealed declines in teachers’ perceptions of school climate prior to principal departure, continuing up to at least 1 year after the transition. As their analyses demonstrated, however, the different findings depended on the type of turnover. No significant school climate changes were observed for transfers or promotions either prior to or after turnover; however, significantly less positive climates were found in the 2 years preceding a principal exit of the system or demotion, with significant climate improvements in evidence following the transition.

Finally, principal turnover can result in significant costs to schools, districts, and states. One study found that a conservative estimate of the cost (including preparation program, hiring, signing, internship, mentoring, and continuing education) to replace a principal in a large urban district (New York City) was $75,000, and a significantly higher cost was thought to be likely for under-resourced schools with high turnover rates (School Leaders Network, 2014). A study of South Carolina districts found a relatively lower cost, ranging from $10,000 to $51,000, with an average cost of approximately $24,000 (Tran, McCormick, & Nguyen, 2018). This study included a narrower range of costs than the New York City study (examining personnel, materials/supplies, and facilities for interviewing), and excluded preparation or professional development costs. In addition, the cost of living is significantly lower in South Carolina, which may have contributed to the difference in findings. Tran et al. (2018) suggested that initiatives to raise principal salaries and other principal retention efforts potentially offered more cost-effective endeavors than principal replacement.

Strategies to Improve Principal Retention

Researchers have suggested a number of strategies designed to improve the chances of effective principals remaining in schools. Strategies in the areas of high-quality principal pipeline and professional development, improved working conditions and compensation, greater autonomy and decision making, and reformed accountability systems have been described in the literature (Levin & Bradley, 2019). These strategies have received varying levels of research support, both direct and indirect, but all address the factors identified as important in reducing principal turnover and, therefore, at least suggest a research-based rationale for the potential to improve principal retention (Herman et al., 2017).

High-Quality Principal Pipeline and Professional Development Initiatives. Improved principal effectiveness can lead to increases in principal retention. Some research evidence suggests that providing ongoing principal professional development activities such as coaching and/or mentoring holds promise for improving principal practice and reducing teacher attrition (Goldring, Grissom, Rubin, Rogers, & Clark, 2018; Jacob et al., 2015; Lochmiller, 2014). For example, Goldring et al. found in an analysis of implementation that shifting the principal supervisor’s role from compliance to focus more on instructional leadership and principal support (through one-on-one coaching and peer observations) resulted in more positive and productive principal-supervisor relationships.

The McREL Balanced Leadership Program provides research-based guidance in the form of 21 key leadership responsibilities (e.g., monitoring instruction, involvement in curriculum and instruction) that help principals become more effective and improve their capacity to enhance student achievement (Jacob et al., 2015; Marzano et al., 2005). A recent randomized control trial study of rural schools in Michigan showed that the program reduced principal and teacher turnover and improved principal efficacy; however, no benefits to student achievement were observed (Jacob et al., 2015). The most likely method to improve retention is principal development tailored to individual and district needs, and that includes networking opportunities with similar peers (e.g., cohort approach), with plenty of development and support targeted to early-career principals (Edwards et al., 2018).

Efforts to improve the quality of school leaders broadly include preparation, recruitment, training, evaluation, and ongoing development; improvements in these processes are likely cost-effective approaches to ultimately improving principal retention and school outcomes (Leithwood, Seashore Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, 2004). Characteristics of principal preparation have been shown to influence principal quality, although states rarely require these programs to demonstrate evidence of effectiveness for outcomes such as principal retention (Herman et al., 2017). Descriptive research has shown that the New Leaders program, which includes selective recruitment and admissions, training and endorsement, and supports for principals early in their tenure, demonstrated higher percentages of New Leader than non-New Leader principals who remained at their school for 3 or more years in 9 of 11 districts studied (Gates et al., 2014a). Many New Leaders principals have gone on to serve as principal supervisors, which count as turnover statistics but may also yield leadership benefits at the district level (Gates et al., 2014b).

Attracting effective principal candidates is most acute for hard-to-staff schools, which often lack applicant pools with sufficient numbers of candidates who have relevant leadership experience, leading to high levels of attrition and ongoing cycles of hiring replacements, particularly in low-income urban settings (Center on School Turnaround, 2017; Goldhaber, Lavery, & Theobald, 2015). The leadership pipeline policy perspective seeks to address these needs and “link principal preparation, development and support, and evaluation, and align each of these systems with leadership standards” (Korach & Cosner, 2017, p. 265). In 2011, the Wallace Foundation’s Principal Pipeline Initiative (PPI) invested in six large high-need urban districts, engaging these districts and preparation programs in collaborative recruitment and selection efforts aligned with district leadership standards (Turnbull, Riley, & MacFarlane, 2015). The initiative identified four research-based components of a principal pipeline (Turnbull, Anderson, Riley, MacFarlane, & Aladjem, 2016):

Leadership standards to guide all pipeline activitiesPre-service preparation for assistant principals and principals (including both training and recruitment, as well as selection into these opportunities)Selective hiring and placementOn-the job induction, evaluation, and support

Research addressing the implementation of PPI showed that districts created standards and competencies for school leaders, and that this work constituted a “quick win” and helped provide a common language for leaders within districts as they collaborated with external partners (Turnbull et al., 2016). District-developed standards further guided preparation, hiring, evaluation, and support of principals, and PPI supported districts as they developed tracking systems that documented where leaders were prepared, their career paths, and evaluation data. These tracking systems, in turn, provided data to inform preparation/development programs and decisions about hiring and placements, as well as specific principal competency needs within the district (Turnbull et al., 2015).

Subsequent research compared changes in outcomes in PPI district schools with changes in outcomes at similar schools in non-PPI districts, and found significantly larger improvement in math and reading, and significantly higher rates of principal retention (Gates, Baird, Master, & Chavez-Herrerias, 2019). Specifically, principals in PPI districts were 5.8 percentage points more likely to remain in their school for at least 2 years and 7.8 percentage points more likely than newly placed principals in comparison schools to remain in their school for at least 3 years (Gates et al., 2019).

A subsequent cost-effectiveness analysis revealed that PPI’s cost of $42 per student per year did not represent a “big ticket” district expenditure, with participating districts devoting 0.4% of their current expenditures to principal pipeline activities (Gates et al., 2019; Kaufman, Gates, Harvey, Wang, & Barrett, 2017). This finding is consistent with other research that demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of successful school leadership initiatives, such as the National Institute for School Leadership’s Executive Development Program (Nunnery, Ross, Chappell, Pribesh, & Hoag-Carhart, 2011; Nunnery, Yen, & Ross, 2011). Currently PPI is being piloted in 90 school systems in 31 states to determine if the program can be replicated in other school contexts (Superville, 2020).

Improved Working Conditions and Compensation. This overview has established that many aspects of the school environment influence principals’ retention, and, indeed, improving principal working conditions is thought to be crucial to keeping effective school leaders in the schools that need them most (Simon & Johnson, 2015). Working conditions that are critical include job stress, time commitment, student demographics and mobility, degree of autonomy, and available fiscal resources (Fuller et al., 2015). Supporting principals’ time management may improve working conditions and contribute to principal retention. The most effective principals are highly visible in their schools and spend a significant amount of time in the classroom monitoring new instructional practices (Goldring et al., 2015). Successful principals make purposeful classroom visits and have follow-up conversations with teachers on data-driven instructional issues designed to improve student learning and achievement (Copeland & Neeley, 2013).

Research in urban schools found that time spent by principals directly coaching teachers on how they could improve their instruction and support student academic needs positively correlated with achievement gains and school improvement (Grissom, Loeb, & Master, 2013). Unfortunately, this study of urban schools showed coaching by principals to be relatively rare, with informal walk-ins much more common. To combat this issue, the literature on effective schools suggests that the assistant principal manage administrative roles and duties, allowing the principal more time to engage with teachers (Wallace Foundation, 2013).

Turnover research suggests that increased resources and funding to schools to address poor conditions due to insufficient instructional resources and poor school climate can enhance the retention of effective principals (Burkhauser et al., 2012; Farley-Ripple et al., 2012). Increased district supports through programs such as those described previously (coaching, mentoring, etc.) can also equip principals with the skills they need in these settings.

Principal pay is often not considered to be commensurate with the perceived demands of the job, which can result in fewer potential candidates and higher rates of turnover (Baker et al., 2010; DiPaola & Tschannen-Moran, 2003). Indeed, in some cases, pay for principals may be lower than pay for experienced teachers, which may create a disincentive to move to administration (Levin & Bradley, 2019). Some experts seeking to improve schools have called for inclusion of school leaders in pay-for-performance reward systems (e.g., Schuermann, Guthrie, Prince, & Witham, 2009). The Pittsburgh Principal Incentive Program provided performance-based financial incentives ($2,000 permanent salary increases based on performance and annual bonuses of up to $10,000 based on school and student achievement measures), along with targeted professional development and support, to public school principals to build their capacity as instructional leaders. One study of the initiative found that participation correlated with improvements to student achievement in high-need schools and for low-performing students, and researchers attributed the findings to the bonus system design, which provided extra compensation for principals working in these school environments (Hamilton, Engberg, Steiner, Nelson, & Yuan, 2012).

Principals reported, however, that money was not an incentive for them to work harder or change their practice, and they were much more likely to attribute improvement in their leadership behavior to support and feedback rather than financial incentives (Hamilton et al., 2012). Findings on principal mobility suggested that the bonuses impacted principal mobility: Higher than average bonuses spurred some principals to move to the administration at the central office level, while those receiving lower than average bonuses were likely to be demoted to assistant principal positions.

A Mathematica Policy research study of implementation of the Teacher Incentive Fund program found that less than 30% of districts awarded performance bonuses to principals that were “differentiated, substantial, or challenging to earn” (Chiang et al., 2015, p. 1), and most bonuses were based solely on schoolwide achievement and just two observations. In addition, most of those principals rated low on student achievement measures received average or above-average observation ratings, suggesting that relying solely on student achievement data for assessing principal effectiveness in pay-for-performance compensation structures is unreliable and unwarranted (Baxter, n.d.; Grissom, Kalogrides, & Loeb, 2015). The National Association of Secondary School Principals (2020) has recommended that performance-based principal compensation include:

State-developed guidelines on performance incentives and clear processes for districts to participateAlignment with school/district improvement plansMultiple principal and leadership effectiveness measures that correlate with college and career readiness state standardsMeasures of principal performance such as self-assessments, documentation of instructional leadership, central office and teacher evaluation, and teacher retention rates

Given that it is often difficult to recruit principals to serve in low-performing schools in high-poverty areas, many researchers recommend that states and districts develop training and placement strategies of better prepared and/or more experienced principals in these schools to both increase achievement and prevent excessive turnover (Burkhauser et al., 2012; Grissom & Bartanen, 2019a, 2019b; Tran & Buckman, 2017). To this end, a review of state Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) plans suggests that a number of states have developed principal learning programs and incorporated incentives and supports to attract and retain highly effective principals in high-need schools (Levin & Bradley, 2019).

Increased Autonomy and Decision Making. Principal retention may also be enhanced by providing increased autonomy for school-level decision making in areas such as budget, staffing, and curriculum (Herman et al., 2017). Many schools have struggled to increase principal autonomy (Honig & Rainey, 2012); however, several high-quality studies found gains in some academic areas, particularly in charter schools, as a result of autonomy initiatives (Abdulkadiroglu, et al., 2011; Steinberg, 2014). Giving principals decision-making authority over staffing, spending, teacher evaluation, and disciplinary policy has been shown to influence principals’ intentions to remain in their schools (Tekelelassie & Villareal, 2011).

Simon and Johnson (2015) described some of the strategies for providing increased school leader autonomy and time management support in high-poverty schools:

[P]rincipals and school-level teams might be given the final say in hiring decisions so that they can cultivate teams of teachers who have shared goals and purposes as well as the collective skillset needed to get the work done… Positions for teacher-leaders would allow principals to strategically distribute some of their responsibilities and decision-making authority to outstanding teachers. Similarly, if principals of high-poverty schools were granted control of their budget, they could hire support staff, such as social workers, college advisors, and parent coordinators, to complement the expertise of their teaching staff and buffer students from the effects of poverty…Districts might grant high-poverty schools additional funds to hire operations managers so principals could focus on instruction, students, and parents. If high-poverty schools offered strong educators unmatched opportunities to develop their skills as leaders, perhaps promising principals would choose to work in them and, in turn, effective and dedicated teachers would follow. (p. 38)

Reforms to Accountability Systems. Recent federal school turnaround programs advocated for strategic staff management at chronically low-performing schools and often included replacement of the principal as a key component of school improvement (Herman et al., 2017). Replacing the principal was thought to be essential to improving a school’s leadership quality while also disrupting dysfunctional processes that inhibit reform (Hassel & Hassel, 2009). Research generally suggests, however, that changing principals does not result in achievement gains (Bartanen et al., 2019; Béteille, et al., 2012; Dhuey & Smith, 2014; Henry & Harbatkin, 2019) unless there is a highly effective replacement, which is often not the case (Bartanen et al., 2019). High-stakes accountability systems in which schools are threatened with sanctions including closure, reconstitution, or takeover have been shown to have higher rates of principal turnover (Mitani, 2018), and these principals were more likely to relocate to higher performing schools (Clotfelter et al., 2006; DeAngelis & White, 2011; Mitani, 2017).

Researchers generally agree that, by making it more difficult to retain principals in schools most in need of excellent leadership, these policies were counterproductive (Figlio & Loeb, 2011). Accountability systems that build principals’ capacity to understand and support teachers’ use of evidence-based instructional practices include (1) high-quality preparation, induction, professional development, and ongoing supports such as mentoring and coaching; (2) accreditation and licensing based on evidence of administrator proficiency in supporting diverse learners to master challenging academic standards; and (3) performance evaluation based on multiple indicators of principals’ instructional leadership competency and their capacity to support students’ college and career readiness (Darling-Hammond, Wilhoit, & Pittenger, 2014; National Association of Secondary School Principals, 2020).

Summary and Conclusions

Principals influence student learning and achievement through their capacity to provide a positive school climate and positive teacher working conditions, and to ensure that high-quality curriculum and instruction are used in the school. Principal stability is essential, particularly in high-need schools. Unfortunately, turnover is all too common, with roughly 20% of principals leaving their schools each year. While the overall turnover rate has taken a slight downturn in the last few years, many districts with large numbers of disadvantaged students have high rates of turnover and report shortages of trained and effective school leaders. Difficult working conditions in many charter schools have likely contributed to the higher turnover rate of public charter school principals compared with that of traditional public school principals.

Younger principals and those with more experience are less likely to turn over, and those who have earned a doctorate are more likely to move but not leave their schools. Less effective principals are more likely to leave the profession or to be demoted to lower level positions. However, some evidence suggests that principals who are rated highly by supervisors are also more likely to leave their schools, many to work at the central office level.

Many students of color attend schools in economically disadvantaged areas, where higher rates of principal churn are more likely to occur. These schools are often staffed by younger and less experienced school leaders, who then move to schools with less poverty, and this process contributes to higher rates of teacher turnover. Low-performing schools, many of which have faced sanctions in accountability systems, similarly must deal with high principal turnover rates.

Working conditions, which may include high stress levels, large workloads, and high rates of disciplinary incidents, also contribute to higher levels of turnover. Principals’ access to high-quality preparation, support, and professional development contributes to lower turnover rates, as does a high level of autonomy and control over certain decision-making processes at the school. Satisfied principals are less likely to leave their schools, but “pull” factors may lure even satisfied principals into leaving. The impact of salary on principal turnover is unclear; it is likely an important factor in principals’ decision making but one that is mediated by other factors such as working conditions and school context. District and policy characteristics also influence turnover, with reduced odds of turnover when principals have tenure protections and union membership, and when policies are instated to improve teacher working conditions.

Principal turnover most often has negative consequences. Higher rates of principal turnover correlate with higher rates of teacher turnover, both initially after the departure of the principal and persisting for at least several years. The type of turnover may matter, as teacher turnover rates are highest when presumably less effective principals are demoted; subsequent leadership improvements have the potential therefore to improve teacher retention. Principal turnover also generally has negative consequences for student achievement; however, reductions in student achievement are highest when principals transfer or are promoted.

When principals are demoted, achievement has been shown to actually improve in the long term. Often, principal turnover results in replacements who have less experience on average, although some success has been found in districts that are able to install highly effective principals in chronically low-performing schools. High rates of principal churn also are usually disruptive to school climate and culture both before and after the transition; however, the demotion and replacement of principals often results in improved climate and culture. Further, principal turnover is costly, and initiatives to improve principal leadership and retention are likely to be less expensive than principal replacement.

The research on strategies to improve principal retention is mostly limited to descriptive studies and noncausal methods of analysis. However, the research has also revealed several key areas that can positively impact schools’ efforts to keep effective principals in the schools that need them the most. Increasing supports for principals through coaching and mentoring show promise, and some causal evidence suggests that programs that promote principals’ use of research-based effective leadership practices may also enhance retention. These programs must be tailored to school and district context; for example, schools in economically disadvantaged communities likely need supports to attract effective candidates and keep them in these communities. Principal pipeline initiatives offer a comprehensive and cost-effective approach by providing recruitment, preparation, ongoing training, and on-the-job supports that have been shown to positively impact student achievement and principal retention.

High stress levels and an excessive workload often contribute to negative working conditions, which increase the likelihood of turnover. Freeing up more time for instructional leadership by distributing certain leadership duties to assistant principals or teacher-leaders may foster principal effectiveness and, in turn, retention. Providing principals working in high-need schools with the resources they need to improve instruction and climate in these schools can foster retention, as can targeted financial incentives that attract highly effective candidates who have a greater likelihood of promoting rapid school improvement in these schools.

In addition, improvements to schools’ disciplinary environments through the use of research-based practices and policies, such as social/emotional learning (Taylor, Oberle, Durlak, & Weissberg, 2017), schoolwide positive behavioral and intervention supports (Horner, Sugai, & Anderson, 2010), and restorative justice (Fronius et al., 2019) programs may contribute positively to improvement of a principal’s working conditions. Research on pay-for-performance strategies, which are often narrowly based on student performance, is mixed; in some cases, they may encourage effective principals to move out of their schools and into central office positions. It is likely that these strategies will need to be coupled with other strategies, described in this overview, that improve working conditions to maximize their impact on retention.

Principals may also be more likely to remain in schools when they are given appropriate autonomy to make decisions in the best interest of school needs in areas such as staffing, budgeting, and curriculum and instruction. Providing this increased autonomy also suggests that the principal is responsible and accountable for increasing the quality of instruction and improving learning. However, high-stakes accountability systems in which the threat of principal replacement is imminent may result in increased turnover and movement to higher performing schools. Accountability systems that promote retention, particularly in high-need schools, should empower school leaders to build teachers’ capacity to use evidence-based instructional strategies. These systems should include the use of high-quality supports, licensing/accreditation based on evidence of proficiency to meet the needs of diverse learners, and multiple measures of leadership performance correlated with career and college readiness.

Citations

Abdulkadiroglu, A., Angrist, J. D., Dynarski, S. M., Kane, T. J., & Parag, A. P. (2011). Accountability and flexibility in public schools: Evidence from Boston’s charters and pilots. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126, 699-748.

Adnot, M., Dee, T., Katz, V., & Wyckoff, J. (2017). Teacher turnover, teacher quality, and student achievement in DCPS. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 54–76.

Baker, B. D., Punswick, E., Belt, C. (2010). School leadership stability, principal moves, and departures: Evidence from Missouri. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(4), 523–557.

Bartanen, B., Grissom, J. A., & Rogers, L. K. (2019). The impacts of principal turnover. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(3), 350–374.

Battle, D. (2009). Characteristics of public, private, and Bureau of Indian Education elementary and secondary school principals in the United States: Results from the 2007–08 schools and staffing survey (NCES 2009-323). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1028.5626&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Battle, D. (2010). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2008-09 principal follow-up survey (NCES 2010-337). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2010337

Baxter, A. (n.d.). Performance incentives for school administrators. Atlanta, GA: Southern Regional Education Board. Retrieved from https://www.ncleg.gov/documentsites/committees/BCCI-6680/Nov 28/2bb_sreb_performance_incentives_handout.pdf

Béteille, T., Kalogrides, D., Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41(4), 904–919.

Boyce, J., Bowers, A. J. (2016). Principal turnover: Are there different types of principals who move from or leave their schools? A latent class analysis of the 2007–08 schools and staffing survey and the 2008–09 principal follow-up survey. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 15(3), 237–272.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2011). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 303–333. Retrieved from https://cepa.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Admin%20Teacher%20Retention.pdf

Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals. Working Paper 17803. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w17803

Burkhauser, S. (2017). How much do school principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 126-145. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c040/3057b9490d6321364d4ace80d06aebcc1a48.pdf

Burkhauser, S., Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., & Ikemoto, G. S. (2012). First-year principals in urban school districts: How actions and working conditions relate to outcomes. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2012/RAND_TR1191.pdf

Cannata, M., Rubin, M., Goldring, E., Grissom, J. A., Neumerski, C. M., Drake, T. A., & Schuermann, P. (2017). Using teacher effectiveness data for information-rich hiring. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(2), 180–222.

Center on School Turnaround and Improvement. (2017). Four domains for rapid school improvement: A systems framework. San Francisco, CA: WestEd. Retrieved from http://centeronschoolturnaround.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/CST_Four-Domains-Framework-Final.pdf

Chiang, H., Wellington, A., Hallgren, K., Speroni, C., Herrmann, M., Glazerman, S., & Constantine, J. (2015). Evaluation of the Teacher Incentive Fund: Implementation and impacts of pay-for-performance after two years, Executive Summary (NCEE 2015-4021). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED560156.pdf

Clark, D., Martorell, P., & Rockoff, J. (2009). School principals and school performance. Working Paper 38. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED509693.pdf

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2006). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85(5), 1345–1380.

Copeland, G., & Neeley, A. (2013). Identifying competencies and actions of effective turnaround principals. Austin, TX: Southeast Comprehensive Center at SEDL. Retrieved from http://secc.sedl.org/resources/briefs/effective_turnaround_principals/

Cullen, J. B., & Mazzeo, M. J. (2007). Implicit performance awards: An empirical analysis of the labor market for public school administrators. Working paper. Retrieved from: http://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/mazzeo/htm/txppals_1207.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., & Pittenger, L. (2014). Accountability for college and career readiness: Developing a new paradigm. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. Retrieved from https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/accountability-college-and-career-readiness-developing-new-paradigm.pdf

Davis, S., Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M. & Meyerson, D. (2005). School leadership study: Developing successful principals. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute. Retrieved from https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/school-leadership-study-developing-successful-principals.pdf

DeAngelis, K. J., & White, B. R. (2011). Principal turnover in Illinois public schools, 2001-2008 (IERC 2011-1). Edwardsville, IL: Illinois Education Research Council. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED518191.pdf

Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663.

DiPaola, M., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2003). The principalship at a crossroads: A study of the conditions and concerns of principals. NASSP Bulletin, 87, 43–65.

Edwards, W. L., Quinn, D. J., Fuller, E. J., & Pendola, A. (2018). Policy brief 2018–4: Impact of principal turnover. Charlottesville, VA: University Council for Educational Administration, University of Virginia. Retrieved from http://3fl71l2qoj4l3y6ep2tqpwra.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Policy-Brief-2018-–-4-Impact-of-Principal-Turnover.pdf

Farley-Ripple E. N., Raffel, J. A., & Welch, J. C. (2012). Administrator career paths and decision processes: Evidence from Delaware. Journal of Educational Administration, 50(6), 788–816.

Figlio, D., & Loeb, S. (2011). School accountability. In E. A. Hanushek, S. J. Machin, & L. Woessman (Eds.), Handbooks in economics: Economics of education (Vol. 3, pp. 383–421). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Persson, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated research review. San Francisco, CA: WestEd. Retrieved from https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/resource-restorative-justice-in-u-s-schools-an-updated-research-review.pdf

Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., Young, M. D. (2015). Working conditions and retention of principals in small and mid-sized urban districts. In I. E., Sutherland, K. L. Sanzo, & J. P. Scribner (Eds.), Leading small and mid-sized urban school districts (Vol. 22, pp. 41–64). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Fuller, E. J., & Young, M. D. (2009). Tenure and retention of newly hired principals in Texas. Austin, TX: University Council for Education Administration, University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228660740_Tenure_and_Retention_of_Newly_Hired_Principals_in_Texas

Fusarelli, B. C., Fusarelli, L. D., & Riddick, F. (2018). Planning for the future: Leadership development and succession planning in education. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 13(3), 286–313.

Gates, S. M., Baird, M. D., Master, B. K., & Chavez-Herrerias, E. R. (2019). Principal pipelines: A feasible, affordable, and effective way for districts to improve schools. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2666.html

Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., Martorell, P., Burkhauser, S., Heaton, P., Pierson, A.,… Gu, K. (2014a). Preparing principals to raise student achievement: Implementation and effects of the New Leaders program in ten districts. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR500/RR507/RAND_RR507.pdf

Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., Martorell, P., Burkhauser, S., Heaton, P., Pierson, A., … Gu, K. (2014b). Preparing principals to raise student achievement: Implementation and effects of the New Leaders program in ten districts:Appendix. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR507z1.html

Gates, S., Ringel, J., Santilbanez, L., Guarino, C., Ghosh-Dastidar, B., & Brown, A. (2006). Mobility and turnover among school principals. Economics of Education Review, 25(3), 289–302. Retrieved fromhttps://www.academia.edu/24902520/Mobility_and_turnover_among_school_principals

Goldhaber, D., Lavery, L., & Theobald, R. (2015). Uneven playing field? Assessing the teacher quality gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged students. Educational Researcher, 44(5), 293–307.

Goldring, E., Grissom, J. A., Neumerski, C. M., Murphy, J., Blissett, R., & Porter, A. (2015). Making time for instructional leadership, Vol. 1: The evolution of the SAM process. New York, NY: Wallace Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Making-Time-for-Instructional-Leadership-Executive-Summary.pdf

Goldring, E. B., Grissom, J. A., Rubin, M., Rogers, L. K., Neel, M., & Clark, M. A. (2018). A new role emerges for principal supervisors: Evidence from six districts in the Principal Supervisor Initiative. New York, NY: Wallace Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/A-New-Role-Emerges-for-Principal-Supervisors.pdf

Goldring, R., & Taie, S. (2014). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 principal follow-up survey (NCES 2014-064 rev). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2014064rev

Goldring, R., & Taie, S. (2018). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2016–17 principal follow-up survey (NCES 2018-066). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018066.pdf

Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552–2585. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fbfb/e9a11dbb70024657844d4dc3aebe17518d67.pdf?_ga=2.128613770.767184246.1585056331-1379934943.1547574243

Grissom, J. A., & Bartanen, B. (2019a). Principal effectiveness and principal turnover. Education Finance and Policy, 14(3), 355–382. Retrieved from https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.1162/edfp_a_00256

Grissom, J. A., & Bartanen, B. (2019b). Strategic retention: Principal effectiveness and teacher turnover in multiple-measure teacher evaluation systems. American Educational Research Journal, 56(2), 514–555.

Grissom, J. A., Blissett, R. S. L., & Mitani, H. (2018). Evaluating school principals: Supervisor ratings of principal practice and principal job performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 446–472.

Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28.

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Master, B. (2013). Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educational Researcher, 42(8), 433–444.

Hallinger, P., Wang, W.-C., & Chen, C.-W. (2013). Assessing the measurement properties of the Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale: A meta-analysis of reliability studies. Educational Administration Quarterly, 49(2), 272–309.

Hamilton, L. S., Engberg, J., Steiner, E. D., Nelson, C. A., & Yuan, K. (2012). Improving school leadership through support, evaluation, and incentives: The Pittsburgh Principal Incentive Program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2012/RAND_MG1223.pdf

Hassel, E. A., & Hassel, B. (2009). The big U-turn: How to bring schools from the brink of doom to stellar success. Education Next, 9(1), 21–27. Retrieved from https://www.educationnext.org/the-big-uturn/

Herman, R., Gates, S. M., Arifkhanova, A., Barrett, M., Bega, A., Chavez-Herrerias, E. R., … Wrabel, S. L. (2017). School leadership interventions under the Every Student Succeeds Act: Evidence review. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1500/RR1550-3/RAND_RR1550-3.pdf

Henry, G. T., & Harbatkin, E. (2019). Turnover at the top: Estimating the effects of principal turnover on student, teacher, and school outcomes (EdWorkingPaper 19-95). Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute at Brown University. Retrieved from https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai19-95.pdf

Hitt, D. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 531–569.

Honig, M. I., & Rainey, L. R. (2012). Autonomy and school improvement: What do we know and where do we go from here? Education Policy, 26(3), 465–495.

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Anderson, C. M. (2010). Examining the evidence base for school-wide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptional Children, 42(8), 1–14. Retrieved from http://dropoutprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SolutionsFeb2011_horner_sugai_anderson_2010_evidence.pdf

Horng, E., Kalogrides, D., Loeb, S. (2009). Principal preferences and the unequal distribution of principals across schools. Working Paper 38. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/33311/1001442-Principal-Preferences-and-the-Unequal-Distribution-of-Principals-across-Schools.PDF

Husain, A. N., Miller, L. C., & Player, D. W. (2019). You can only lead if someone follows: The role of teachers’ assessment of principal quality in principal turnover. Working Paper 69. Charlottesville, VA: EdPolicyWorks, University of Virginia. Retrieved from https://curry.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/epw/69_Teacher_Assessed_Principal_Quality_and_Turnover.pdf

Jacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL Balanced Leadership Program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1003.6694&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Kaufman, J. H., Gates, S. M., Harvey, M., Wang, Y., & Barrett, M. (2017). What it takes to operate and maintain principal pipelines: Costs and other resources. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2000/RR2078/RAND_RR2078.pdf

Korach, S., & Cosner, S. (2017). Developing the leadership pipeline: Comprehensive leadership development. In M. Young & G. Crow (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of school leaders (pp. 262–282). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Yee, D. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5), 1411–1449. Retrieved from https://research.steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/media/users/sg158/PDFs/schools_as_organizations/SchoolOrganizationalContexts_WorkingPaper.pdf

Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235–261.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2019). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership and Management. Advance online publication. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332530133_Seven_strong_claims_about_successful_school_leadership_revisited

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turnaround: How successful school leaders transform low performing schools. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Leithwood, L., Seashore Louis, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. New York, NY: Wallace Foundation.

Levin, S., & Bradley, K. (2019). Understanding and addressing principal turnover: A review of the research. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/NASSP_LPI_Principal_Turnover_Research_Review_REPORT.pdf