Multitiered System of Support

Multitiered System of Support.pdf

States, J., Detrich, R. & Keyworth, R. (2017). Overview of Multitiered System of Support. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/school-programs-multi-tiered-systems.

Multitiered system of support (MTSS) is a conceptual framework for organizing service delivery to students. Forming the nucleus of MTSS are adoption and implementation of a continuum of evidence-based interventions, starting with universal academic and social interventions and leading to increasingly intensive methods to ensure improved outcomes for students not benefiting from the universal practices (Harlacher, Sakelaris, & Kattelman, 2014). As a data-based decision-making model, MTSS is constructed around frequent performance screening, research-supported instruction, and timely intervention for those not achieving proficiency. MTSS is often mistakenly seen as a set of scripted practices for teachers to ensure that students succeed. However, MTSS is not a specific practice or even a set of practices, but rather a framework for aligning an organization’s resources to address student needs in the most effective way.

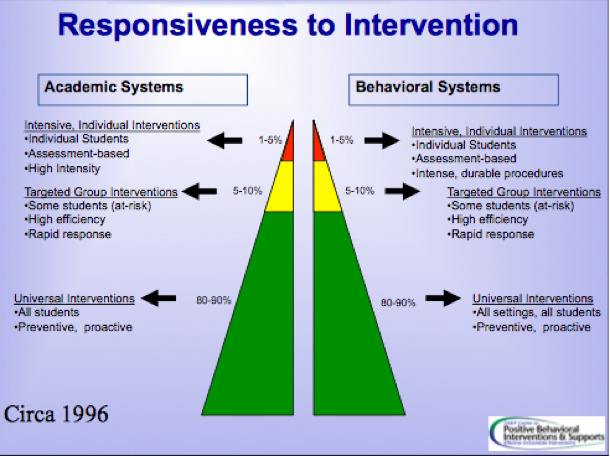

MTSS architecture is most often based on three tiers of service for cost-effective mobilization of resources necessary to implement interventions aimed at promoting success for all students:

Tier 1 = Universal support. Core curriculum and practices are delivered to all students. Intervention is considered effective if about 80% of students make adequate progress. Tier 2 = Heightened support (approximately 15%). Within the core instruction, increased services and remediation using small groups or tutoring are provided to those requiring added support. Approximately 15% of students for whom universal support is inadequate should benefit from this level of intervention. Tier 3 = Intensive support (approximately 5%). Individualized or pinpointed services are provided to students who have not succeeded in tiers 1 and 2.

Some MTSS models may include special education but do not limit it to students qualifying for special education. Examples outside of special education are after-school tutoring and individualized reading intervention using a curriculum outside of core.

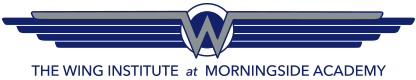

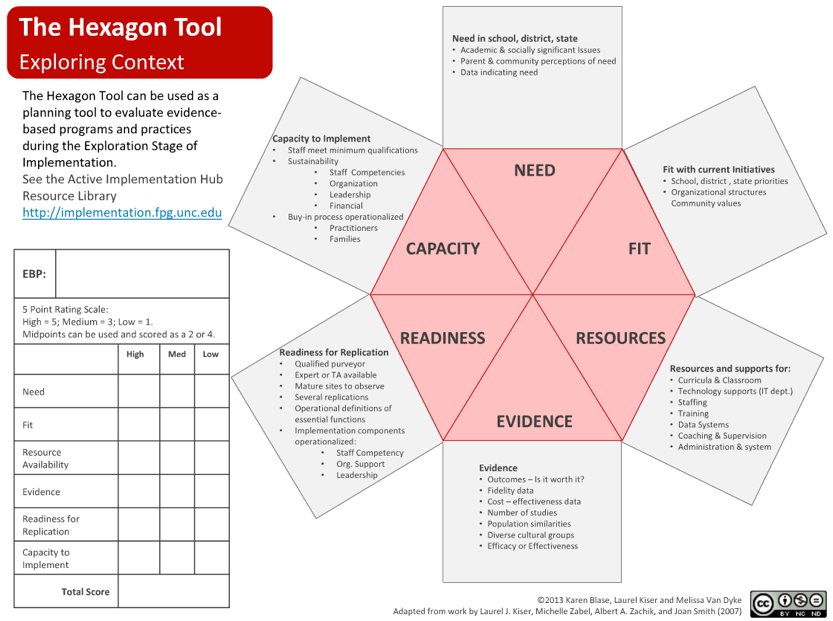

Figure 1. The multitiered model is a framework based on an increasing continuum of support using evidence-based practices to improve all students’ academic and conduct outcomes (Sugai, 2013). Response to intervention (RtI), the best known multitiered approach, is illustrated here.

As a framework, MTSS is devised to accommodate the use of a wide range of curricula and practices that have been vetted through rigorous research. It is the umbrella under which many educational initiatives including positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS), response to intervention (RtI), and differentiated accountability (DA) fall. These initiatives are prime examples of models built around core elements (multitiered levels of support, evidence-based practices, universal screening and ongoing progress monitoring, data-based decision making, and fidelity of implementation) to effectively deliver and sustain interventions. A growing knowledge base now offers strong evidence to support the effectiveness of the multitiered model for improving both academic and social outcomes (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Stoiber & Gettinger, 2016). Of the many initiatives embracing the multitiered model, the most widely known is RtI, a multitiered approach focused on helping students succeed academically (Figure 1).

History of Multitiered System of Support

Before the advent of MTSS, the discrepancy model was commonly used to identify students with learning and emotional challenges. A framework for assessing and delivering services to students who have fallen behind peers or are behind grade level standards, the discrepancy model documents the discrepancy between a student’s aptitude and achievement, and uses this information to decide whether the student is eligible for additional support. The model was widely adopted following the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (EHA, 1975), enacted by the U.S. Congress as the legal basis for determining qualification for special education services. In the following decades, educators found the model to be inadequate and many began referring to it as the “wait to fail” model, as students often spent years failing and falling behind before being identified for vital services. These delays in the delivery of interventions proved a severe flaw in the model (Gresham, 2002).

To remediate this defect, educators began looking for models capable of eliminating delays in service delivery. Research strongly supports early intervention as a powerful strategy for remediating many academic and behavioral issues. The longer teachers wait to intervene, the more challenging it is to remediate problems (Hattie, 2009). Ultimately, MTSS emerged as an alternate to the discrepancy model, as it incorporates early intervention as an indispensable feature to overcome the weakness of the earlier model.

The shortcomings of the discrepancy model are not limited to delayed detection of struggling students. It has many other failings (Gresham, 2001; Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003):

Overidentification of students with learning disabilities Overrepresentation of minorities in special education Too many students identified by the screening tools as at risk but who later perform satisfactorily on the criterion measure (i.e., too many false positives) Variability of identification rates across states and districts

The MTSS framework stemmed from the multitiered public health model, which began achieving remarkable successes at the turn of the 20th century. The public health model was conceptualized as a cost-effective means to improve health and quality of life through prevention and treatment of disease and other physical conditions. It was developed to address the need, imposed by limited resources, to be selective in determining where, when, and how to intervene for maximum results. The public health model proved to be both effective and efficient in appreciably reducing mortality while achieving a significant improvement in quality of life. Deaths from infectious diseases rose dramatically during the 19th century as the population shifted from rural areas to cities, but thanks to the efforts of the public health services, deaths declined markedly resulting in a sharp drop in infant and child mortality (Grove & Hetzel, 1968). The years between 1900 and 1990 saw a 29.2-year increase in life expectancy (Hoyert, Kochanek, & Murphy, 1999). The multitiered framework was so successful that it was subsequently adopted by mental health professionals and eventually embraced by educators (Muñoz, Mrazek, & Haggerty, 1996).

Multitiered System of Support Process

When employed effectively, a multitiered approach prevents problems of students falling behind, allows for earlier identification of at-risk students, and delivers results in a more cost-efficient manner than traditional approaches (Eldevik et al., 2009; Horn & Packard, 1985). MTSS interventions in education are organized from least to most demanding and exacting. This strategy inevitably results in the need to assign additional resources to support the increasingly intensive involvement of teachers and support personnel when universal, or tier 1, interventions fall short of achieving results and more individualized approaches are required at the second and third tiers. Successful MTSS implementation is a complex process requiring the coordination of resources across a school. The MTSS process involves organizing and integrating the following tasks and services:

Gathering accurate and reliable screening data Correctly interpreting and validating data Using data to make meaningful instructional changes when a student is struggling Identifying resources and personnel with the demonstrated capacity to implement evidence-based practices Establishing and managing increasingly intensive tiers of support Evaluating the process at all tiers to ensure the system is working Redesigning curriculum and practices when initial interventions fail to remediate the problem

Essential Practice Elements of a Multitiered System of Support

The MTSS framework comprises a set of interacting practice elements: universal screening, data-based decision making and problem solving, performance feedback and progress monitoring, and system progress monitoring. These elements are combined into a package to maximize the capacity of each, as well as establish a structure in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts (Chorpita, Becker, & Daleiden, 2007).

Universal Screening

Screening of all students is fundamental to MTSS as it is the means for identifying and predicting which students may be at risk of failing to meet educational outcomes for their grade level. These initial, typically brief assessments are supplemented with additional diagnostic testing and ongoing progress monitoring to corroborate which students are at risk and to reduce the likelihood of false positives (students identified as at risk but who later perform satisfactorily) and false negatives (students not identified as at risk but who do require support). Measures that produce too many false positives squander valuable resources by delivering services to students who are not actually in need; too many false negatives deny students who need assistance. Of the two, the greatest concern in developing effective screening tools is minimizing false negatives.

Universal screening focuses on skills that are highly predictive of future outcomes (Jenkins, Hudson, & Johnson, 2007). Ample evidence exists that valid and reliable early indicators are available to guide when and how to intervene with students. This is truer for academic measures in elementary grades than in middle school and high school. Good measures for social behavior are less well established in terms of reliability and validity. Many of these early indicators accurately predict success in subsequent lessons and subjects, test scores, grades, and graduation rates (Celio & Harvey, 2005). Reliable indicators range from expressive and receptive vocabulary, level of self-control, word reading/text fluency, ability to achieve reading competency by fourth grade, and phonological awareness.

Universal screening is typically conducted three times per school year, in fall, winter, and spring. Effective screening demands assessments that accurately, reliably, and efficiently measure student performance against standards. An instrument must demonstrate that it is reliable, valid, and practical to administer before being adopted as a universal screening tool.

Reliability. To be considered reliable, a universal screening tool must achieve similar results when different teachers use the same screening measure with the same student. Unreliable results bring into question the credibility of the assessment. Using screenings with high reliability ensures that students identified for intervention are consistently identified from one assessment to another, across time, and from one scorer to another. This increases the likelihood that the assessment method will produce stable results under standard conditions.

Validity. To be considered valid, a universal screening tool must measure what it is designed to measure. Two types of screening instruments are available to educators: direct and indirect measures. Direct measures specifically assess targeted student performance outcomes. For example, a valid direct measure can be a final test. The test is a direct measure if it requires students to specifically demonstrate knowledge required to pass the course. An example of a valid indirect measure is an office discipline referral, which does not directly measure student behavior but rather is a measure of the teacher’s behavior: sending a student to the office. As an indirect measure, an office discipline referral is a valid indicator because it correlates closely to student behavior. As such referrals are tracked in most schools, they perform well as a surrogate for a direct measure of student behavior.

Practicality. Effective screening instruments must strive to be concise and straightforward, and require a minimum of the teacher’s time to administer. Screenings that can accurately and quickly identify students who are lagging behind peers are essential when the goal is for teachers to minimize time spent on assessment and maximize time available for instruction (Hall, 2007). Screening measures should be simple enough to be implemented by the average teacher and within normal classroom routines (Jenkins, 2003). Screening measures that violate these principles risk being underused and eventually being discarded because they make the job of assessment too burdensome.

Data-Based Decision Making and Problem Solving

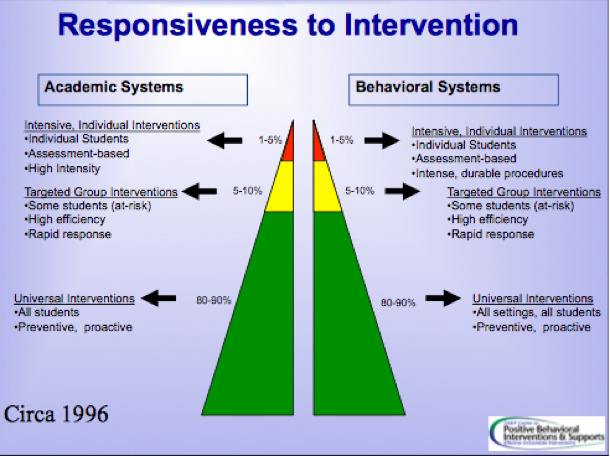

Teachers make as many as a thousand decisions in the course of a day, for example, developing and adapting lessons, figuring out how to support struggling readers, and dealing with students who have behavioral challenges (Jackson, 1990). Data-based decision making is a way for education stakeholders to systematically use empirical evidence to make informed decisions about education interventions (policies, practices, and programs). In recent years, however, the evidence-based practice (EBP) movement has raised questions about the effectiveness those decisions. As a paradigm for making decisions that yield the greatest likelihood of producing positive results, EBP (defined as a process for integrating the best available evidence, professional judgment, and stakeholder values and context to increase the probability that solutions work) has been widely embraced in education (Marsh, Pane, & Hamilton, 2006).

Evidence-based decision making is preferable to opinion-based decision making because choices supported by facts and sound analysis are likely to produce superior results than those made on the basis of intuition, conventional wisdom, or anecdotal evidence (Detrich, Slocum, & Spencer, 2013). Opinion-based decision making constructed on personal likes and dislikes, beliefs, and emotion are likely to produce unpredictable results and often lead to negative outcomes for those the decisions are supposed to benefit (Cook, Tankersley, & Landrum, 2013). Given that the consequences for making poor choices in education can have significant and long-lasting impacts on society, constructing a decision-making framework on a foundation that relies on objective evidence, which predictably increases positive outcomes for students, is imperative.

Figure 2. The three prongs of the evidence-based problem-solving model.

Many situations in education provide relatively little, if any, strong evidence to guide decision makers and yet decisions are required. Frequently, the information is very weak, but at other times it is so convincing that reaching agreement to proceed poses no challenge. On most occasions, the evidence falls somewhere in between. The consequence is that educators often must make informed decisions based on partial or imperfect evidence. When working in a real classroom with real children, educators do not have the luxury to wait for thoroughly vetted studies to be made available. Good teaching requires making the best use of the available data as well as the teacher’s own professional experience to operate a classroom proficiently. This necessitates recognizing professional judgment as a key component of effective data-based decision making, despite its limitations. Professional judgment is constrained by the best available evidence and integrated with stakeholder values and the context in which the educator is working. Ultimately, the most important part of the process is ongoing progress monitoring to ensure that executed decisions are producing the desired results and to identify when to make timely adjustments to meet students’ needs.

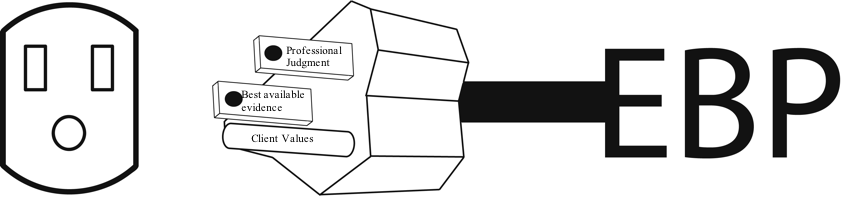

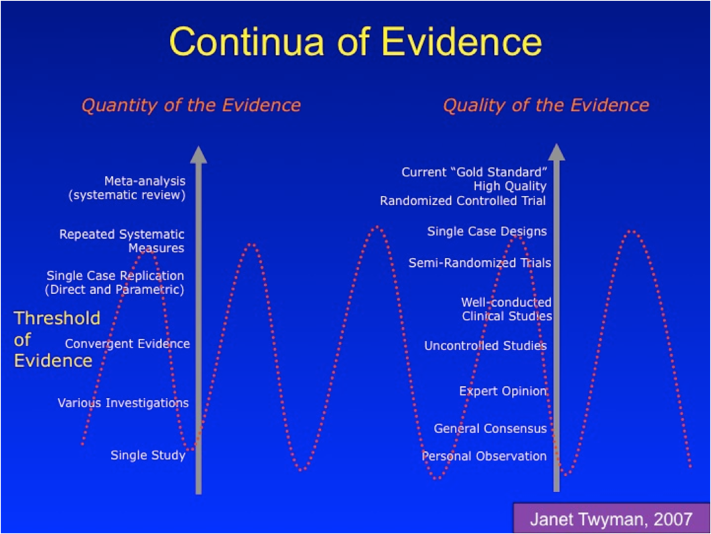

Figure 3. Two critical features are considered in assigning the level of confidence that educators place on practices when selecting education interventions: quantity of evidence and quality of evidence. The higher a practice is on the quantity and quality scales, the greater confidence practitioners have that it will produce reliable results.

The concept of best available evidence suggests that evidence falls along a continuum from very strong evidence at one end to very weak evidence at the other end. In an evidence-based model, results of research are interpreted on continua of evidence to determine if the conclusions exceed the threshold required for making smart choices. The continuum offers a means to evaluate two fundamental factors that reflect the value of evidence for making critical decisions: the quantity of the evidence and the quality of the evidence.

Quantity of Evidence. One variable at play when making effective data-based decisions is the quantity of evidence. A single study, regardless of its quality, does not offer conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of a practice, and thus it is essential to have multiple studies that examine the same phenomenon. Educators gain confidence by replicating findings through multiple studies conducted by independent researchers over time to show that results were not a fluke or due to error. A single study is found at the lower end of the continuum of evidence. As studies are replicated, certainty grows. Replication leads to meta-analysis, the systematic analysis of multiple studies, found at the upper end of the continuum of evidence.

Quality of Evidence. When examining evidence supporting a particular practice, educators are interested in determining the quality, or strength, of the evidence as measured by internal validity (the degree to which the obtained results are a function of the intervention rather than some other variable). The more rigorous the experimental control, the stronger the internal validity (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). Before choosing a practice, a practitioner must have confidence that the research supporting that practice is of sufficient quality to reasonably assume it will reliably produce the predicted effect. Educators need to know how likely it is that a practice will be worth the time and effort needed to implement it. The quality of evidence begins with non-experimental methods such as personal observations, rises with higher degrees of rigor, and culminates in the gold standard of research designs, the randomized controlled trial.

Challenges to Data-Based Decision Making

The broad adoption of the EBP model of data-based decision making by school systems in the early 21st century set high expectations. It seemed reasonable that with the implementation of best practices informed by research, educators would make great strides observable as improvements in student performance. However, progress has been lackluster, as test scores remain stubbornly flat (NCES, 2015). Such discouraging results pose these challenging questions: Is there something fundamentally wrong with the EBP model of data-based decision making? What accounts for the lack of progress?

The vexing problems facing most school systems consist of many components and are convoluted and frequently confounding. Implementing EBP requires the cooperation and commitment of staff at all levels of a school system. Interventions are not executed in isolation. They appear in the context of an existing system that must be acknowledged. Any new evidence-based practice must acknowledge and address a multitude of staff concerns including consistency with the school’s philosophy of education and current practices, and being achievable with available resources. The evidence-based practice must be capable of mitigating forces that are inevitably present and actively resist change. Unfortunately, all too often new practices are introduced without laying the necessary groundwork for implementing and sustaining the changes.

Perplexing and challenging problems like this have been called “wicked problems.” A wicked problem is a social or cultural problem that is difficult to solve, as it comprises a labyrinth of entangled factors that influence each other (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Implementing an evidence-based practice happens in the real world, where those charged with implementation must work with incomplete or contradictory data, rapidly changing boundaries and requirements, logistical impediments that arise in training large numbers of people, objections from significant segments of the workforce invested in maintaining the status quo, the economic cost of implementing solutions, and interconnected systems impacted by change. Acquiring and sustaining the school’s commitment to implement interventions over many years pose additional challenges. Wicked problems rarely have simple solutions and are highly susceptible to generating unintended consequence.

On their own, evidence-based practices aren’t enough to solve wicked problems. Without the development and nourishment of supporting systems, evidence-based practices are as likely to fail as non-evidence-based practices (Farley et al., 2009). Once a practice with a strong research base is introduced, itis best sustained when the practice is embedded and becomes an integral part of a systemwide endeavor. This type of change involves arranging key contingencies that reinforce and maintain critical implementation factors. They include gaining the buy-in and commitment of staff before implementation, eliminating irrelevant or ineffectual practices to lighten the workload of staff, clarifying expectations for personnel, designing and applying effective training methods, and adopting systematic and regular performance monitoring to ensure treatment integrity and desired outcomes (Fixsen, Blase, Horner, & Sugai, 2009: Fixsen, Blase, Naoom, & Wallace, 2009). The adoption of systematic and regular performance monitoring, which requires many of the same efforts needed to implement the new practice, could be considered an innovation in its own right.

The best way to tackle the challenges of implementation is with a framework that acts as the foundation for unifying and supporting complementary practices that promote a common vision and mission (Gresham, 2007). MTSS provides administrators and teachers with a universal platform to effectively and efficiently actualize the six stages of implementation identified in implementation science: exploration and adoption, program installation, initial implementation, full operation, innovation, and sustainability (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, & Friedman, 2005). By embracing this model, schools can more effectively and efficiently communicate, align, and integrate interventions that will work and last. MTSS provides strategies for overcoming obstacles and issues triggered when implementing change in schools. The MTSS framework accommodates key strategies to more productively manage implementation of an evidence-based practice: adopting interventions that directly target key school and student goals and objectives, selecting interventions compatible with student and staff values, ensuring that staff are adequately trained to execute the practice, choosing a practice that is a good fit for the school’s culture and does not conflict with existing practices, providing clear and objective protocols and procedures needed to take the practice to scale, ensuring systems and resources are available that promote treatment integrity, and establishing long-range plans for sustaining the practice (Fixsen et al., 2005).

For MTSS to produce exemplary outcomes requires a coordinated effort across a school. It is not sufficient to have a few of the school staff committed to the new practice. Effective leadership must create and nurture the right organizational climate if it is to establish common values, a common vision, and a common language that are embraced and broadly supported by a significant majority of school personnel. Positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS) has enshrined this approach into its policies by mandating buy-in from 80% or more of the staff before agreeing to enter a school (Turnbull, et al., 2002). Relying on a single champion often leads to failure when staff actively resist the change. Being overly dependent on one or just a few individuals also creates an unstable environment in which efforts can easily be undone as a consequence of the high turnover rate in school systems (Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008). The potential for such problems suggests the need to rethink how initiatives are managed and led. The path forward is to adopt approaches that involve multiple levels of the school system (superintendents, principals, teachers, and parents) and to build redundancy into the system with a leadership model of support such as distributed leadership. Leadership vacuums created by high staff turnover can be emolliated by a shift away from the autocratic leadership, or heroic leadership, model (heavily reliant on a single individual) toward an approach that shares and delegates responsibilities, activities, and functions of leadership across the workforce (Marturano & Gosling, 2008). MTSS provides the necessary structure for increasing staff engagement and spreading out leadership.

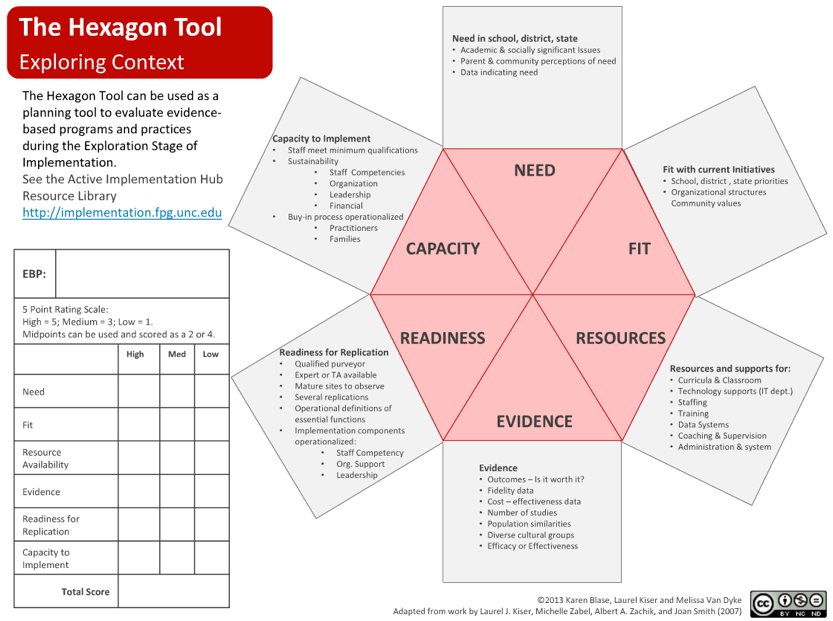

It is common for organizations to shortchange the implementation process and underestimate its importance. Successful implementation takes time. All new initiatives should be considered works in progress, and full implementation should only be considered achieved when the practice becomes routine and the staff describes it as a part of the school’s culture. Full implementation takes up to 5 years. This can be problematic considering that the average life of a school reform initiative in the United States is 18 to 48 months (Latham, 1988). Further confounding this picture is research that finds initiatives produce small effects (on average, 0.25) until the fifth year, with the real benefits appearing by the seventh year and beyond (Borman, Hewes, Overman, & Brown, 2003). MTSS provides the organizational structure essential for sustaining practices so they can reach maturity and produce maximum effects. The National Implementation Network (NIRN) provides educators with an array of resources to support effective implementation. The NIRN hexagon tool is an example of a planning instrument designed to assist in selecting the best practices for a particular school during the exploration stage of implementation.

Figure 4. The National Implementation Network hexagon tool is a data-based decision-making instrument for negotiating the complexity of elements that must be addressed to effectively solve problems in education.

Performance Feedback and Progress Monitoring

Feedback has long been touted as a useful method for improving performance in sports and business, and it is difficult to overstate the important role it plays in MTSS in education. Feedback enables students to understand what is being taught and gives them clear guidance on how to improve their performance. Classroom teachers depend heavily on both formal and informal feedback as a teaching technique each day. Research has found that the effective use of feedback is more consistently correlated with student achievement than all other teaching practices, regardless of student age, socioeconomic status, or race (Bellon, Bellon, & Blank, 1991).

Progress monitoring (also known as formative assessment, ongoing assessment, and rapid assessment) is at the core of feedback and a foundation practice of MTSS. It is among the most powerful means for schools to measure performance so that staff can receive frequent and ongoing feedback on the effects of interventions. Effective progress monitoring, which includes universal screening, makes it possible for educators to know if students are learning, progressing toward agreed-upon outcomes, and benefiting from the school’s curriculum and teachers’ instructional methods. Progress monitoring is vital in ensuring not only that evidence-based practices are implemented as designed, but that treatment integrity is maintained (Hallfors & Godette, 2002).

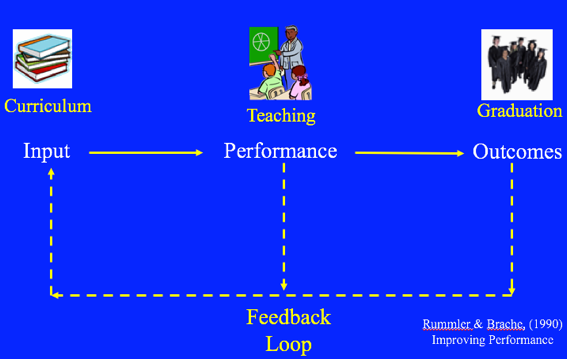

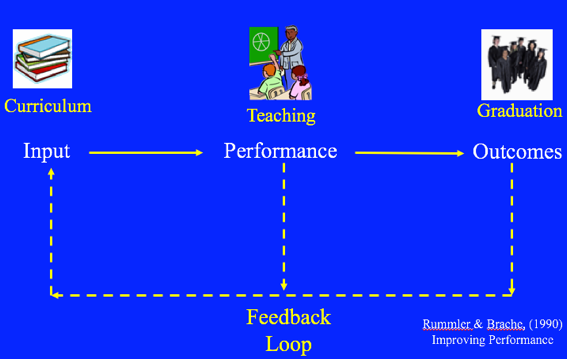

MTSS is firmly rooted in the tradition of monitoring student performance, but monitoring only student performance is not sufficient. Effective MTSS monitors the progress of a range of systems that must be in place and functioning as designed if student achievement is to be maximized. Research on continuous improvement recognizes frequent monitoring at multiple levels of education services (Rummler & Brache, 1990). These include formative assessment of student performance; instruction delivery and treatment integrity; scrutiny of support systems to ensure the availability of resources; and data tracking of key indicators (input, process, and outcomes) (Wayman, Midgley, & Stringfield, 2006).

Student Progress Monitoring

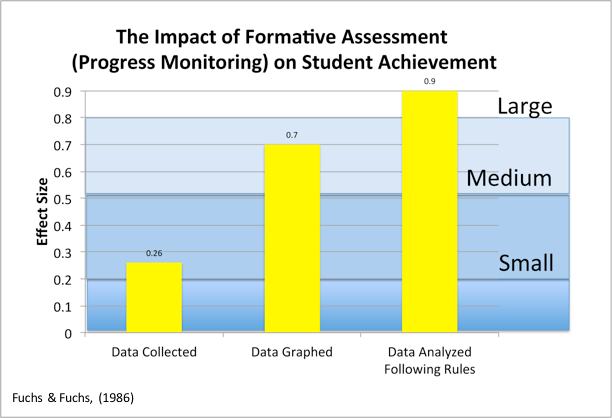

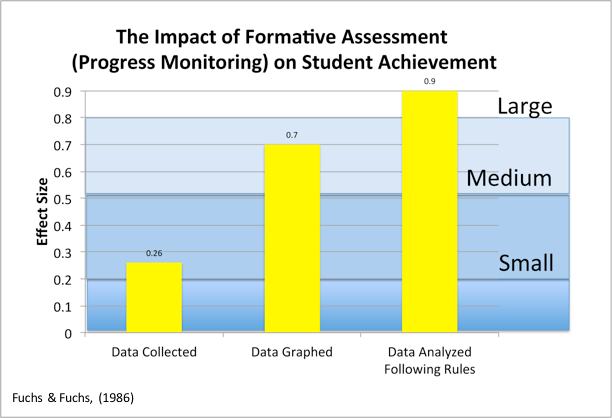

Figure 5. Fuchs and Fuchs (1986) meta-analysis of the effects of progress monitoring on the achievement of students with special needs established an effect size of 0.90.

Although summative assessment, an appraisal of learning at the end of an instructional unit or at a specific point in time, is an important tool for monitoring the overall effectiveness of a school or classroom, it is no substitute for progress monitoring. Summative assessment occurs only once or twice a year whereas progress monitoring is frequent and ongoing, beginning with universal screening and proceeding with regular assessments throughout the school year.

Progress monitoring provides essential data for teachers to identify which students are potentially at risk of falling behind standards. This information is necessary to maximize the educational experience for all students and not just those who are struggling. It provides teachers with insight into how and when to improve instructional strategies and curriculum so that vast majority of students, whether high or low performers, succeed academically. Without progress monitoring, teachers and administrators operate in the dark. They are like drivers asked to wear blindfolds—they don’t know where they are going and have no knowledge of where they have been. Progress monitoring offers an effective alternative to driving blind by providing both teachers and students with objective and timely information about performance with respect to specific academic goals. It also offers insight on how to make adjustments to overcome obstacles during the year.

In the absence of systematic progress monitoring, high-performing students most often get by but are not challenged to excel, and low-performing students are consigned to unremitting failure and given no motivation to be engaged. Data on the national level reveal decades of flat student achievement and large numbers of students failing to attain acceptable levels of proficiency, suggesting the need for frequent progress monitoring in addition to summative assessments (NAEP, 2015; OECD, 2017).

Research supports the systematic implementation of progress monitoring as a potent approach to improving student outcomes. A meta-analysis conducted by Fuchs and Fuchs (1986) established an effect size of 0.26 for the impact of progress monitoring (formative assessment) on student achievement of special needs students compared with similar students whose progress was not monitored on a regular basis. The study authors further found the impact of monitoring student progress was significantly enhanced when the data were collected at least weekly and teachers interacted with that data by graphing and then analyzing it using set rules, a procedure that increased the overall effect size to 0.90.

It is notable that simply collecting student performance data had a statistically significant impact on student achievement. Collecting the data without any other intervention produced a 0.26 effect size. This result indicates that the regular act of monitoring performance triggers a change in how teachers are teaching, which in turn significantly impacts student achievement. When the teachers were required to interact with the data through graphing, the impact on student achievement was enhanced dramatically. Graphing increased the effect size to 0.70. Finally, analyzing the data according to set rules boosted the effect size to 0.90. Rules for evaluating the data required the practitioners to analyze student performance at regular intervals and to introduce changes to the instructional program as the data indicated.

Despite these impressive effects, it is important to examine obstacles that must be addressed if teachers are to effectively utilize ongoing progress monitoring consistently. Objections to progress monitoring include the following: It requires too much effort and time, it takes time away from instruction, creating assessments are a challenge, and interpreting the data is difficult (Bennett, 2011). The solution to most of these objections can be found in implementation science. Effective implementation of a progress monitoring system relies on execution: planning; obtaining buy-in (listening to concerns and developing accommodations); involving staff in implementing the system; providing effective training (including coaching); offering ongoing support; using the data; and monitoring implementation. Packages such as Curriculum-Based Measurement, DIBELS, and AIMSweb are good examples of progress monitoring packages available to assist teachers (Hintze, and Silberglitt, 2005; Riedel, 2007; Wayman, Wallace, Wiley, Tichá, & Espin, 2007).

Performance feedback and progress monitoring can be summarized as follows:

Progress monitoring offers critical performance information for teachers as well as students. Performance feedback is not for grading or formal teacher evaluation, but is used for continuous improvement. Progress monitoring is designed to guide teachers and students in trying new approaches when progress is impeded. Progress monitoring is a guidepost for a teacher to ascertain the level of support that a student needs.

System Progress Monitoring

As is the case with any systemwide intervention, MTSS requires that the intervention be regularly monitored. Research suggests that fidelity begins to degrade shortly after training. The key to avoiding this drift is through ongoing monitoring of essential components of the system along with the use of critical outcome measures.

School systems are most often judged by performance outcomes: graduation rates, dropout rates, and standardized test scores. The decades between 1960 and 1980 saw the performance of American students plateau at levels that increasingly troubled parents, educators, and education policy makers. By 1981, the secretary of education, Terrel Bell, empowered the National Commission on Excellence in Education to review the performance of American schools. The commission produced the report A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Education Reform. Its five recommendations urged (a) the teaching of “new basics” consisting of 4 years of English, 3 years of mathematics, 3 years of science, 3 years of social studies, and half a year of computer science in high school; (b) the adoption of more rigorous and measurable standards; (c) extending the school year to make more time for learning the new basics; (d) using enhanced preparation and professionalization to improve teaching; and (e) adding accountability to education (Gardner, 1983).

Attempts to implement these reforms over the next 20 years produced few tangible results. As a result, in 2001, with bipartisan support, No Child Left Behind became law, increasing pressure on schools to improve student performance (NCLB, 2002). NCLB’s remedy was to establish an infrastructure to hold schools and teachers accountable for key outcome measures. The law was designed to remediate decades of inadequate student standardized test scores by promoting highly qualified teachers, making access to funding contingent on raising standardized test scores, and closing chronically failing schools. As a part of the accountability requirements, schools that persistently underperformed had to follow a set of prescribed improvement actions. School improvement was measured through an adequate yearly progress (AYP) reporting system, and schools were mandated to reach AYP proficiency in reading and mathematics by 2014. Despite the massive resources committed to NCLB, overall test scores showed only small gains and failing schools continued to flounder. By 2014, it became clear that NCLB was not producing the desired results. Instead of all schools achieving proficiency as mandated, the majority of schools in the nation were failing to meet expectations. Ultimately, the remedy was to avoid the embarrassment of a systemwide failure by lowering standards and granting waivers to schools (U.S. Department of Education, 2017).

This resounding failure provokes the question, why didn’t more than 30 years of effort to hold schools accountable for key outcome measures produce so little for the billions of dollars invested? One answer to this question can be found in how organizations in other fields have been successful in producing desired results. An examination of thriving health care and commercial organizations reveals that they not only focus on outcomes, but also place a premium on monitoring processes essential to producing desired outcomes. Achieving positive results alone is insufficient if the those results are to be repeatable. Consistent and sustainable performance thrives when the process is effectively managed (i.e., identifying the best practices, training staff in those practices, and then monitoring the staff to be sure they are implementing the practices as designed).

Pioneers in the field of performance management such as William Deming, Tom Gilbert, and Geary Rummler laid down the fundamental tenets of a continuous improvement process that helped propel Japanese and American industries after the Second World War. Their systems approach placed great value on managing and monitoring both outcomes and processes, which needed to work in tandem to produce exemplary results (Deming, 1966; Gilbert, 1978). It is not difficult to see how that approach can be employed in schools. If key educational goals are to be achieved, all school systems must be viewed as interlocking and supporting one another. Holding principals and teachers accountable won’t lead to the desired outcomes unless evidence-based instructional practices are adopted across the school, teachers are trained to use the practices in the classroom, and the teachers are monitored to ensure that treatment integrity is maintained. Placing pressure on school personnel without making sure that the best processes are in place results in frustration and staff escaping the situation (primarily by quitting). Effective systems focus attention on process: selection of best practices, training in the skills known to produce the best results, and creation of feedback loops to keep everyone apprised of how they are doing with respect to the agreed-upon outcomes. As important as it is to monitor student outcomes, for the best results it is equally necessary to sample the process (Gilbert, 1978).

Often, schools do not look at the totality of their organization as an integrated unit that must work together to ensure that all students succeed. Platitudes such as No Child Left Behind and Every Student Succeeds are doomed to failure if outcomes and processes are not attended to and monitored regularly.

Figure 6. Continuous improvement model.

A simplified diagram (Figure 6) provides an overview of the four components of a continuous improvement model for education.

Input: This includes an evidence-based curriculum directly tied to outcomes, teacher training on how to implement the curriculum, resources made available to implement the curriculum, and student assessments before instruction to ensure that instruction is tailored to each student’s level of competency. Performance: Teachers provide sufficient instruction in accordance with MTSS. Outcomes: Objective outcomes are identified. Feedback loop: All three areas (input, performance, and outcomes) must be monitored. They are measured and sampled on a systematic basis to ensure that the system is performing as designed and that personnel receive feedback in a timely manner so they have the opportunity to adapt and make improvements.

Summary

The multitiered system of support provides a framework for schools to organize and manage education services. The goal of MTSS is more effective coordination and alignment of a school’s services to maximize student achievement against standards. MTSS accomplishes this by focusing on the use of explicit instruction practices: well-designed core instruction, differentiated instruction, and individualized interventions as needed. MTSS is not a practice but rather a framework designed to apportion and support an array of practices (universal screening, data-based decision making and problem solving, performance feedback and progress monitoring, and system progress monitoring) to solve many education outcomes. Borrowed from the public health model, MTSS was conceptualized to remedy failings in the discrepancy that led to unacceptable delays in delivering interventions. MTSS allocates and provides services in a timely and cost-effective manner. At its heart is a three-tiered system of support: Tier 1 provides universal support; tier 2, heightened support; and tier 3, intensive support. Tiers 2 and 3 are designed to capture students who are falling behind despite universal support. MTSS is based on strong evidence that early identification of student performance and proper instruction are highly effective and essential if schools are to better educate students. MTSS relies on three essential strategies: (a) monitoring performance through universal screening, ongoing student progress monitoring, and frequent monitoring of key MTSS systems; (b) employing data-based decision making; and (c) using the best available evidence when selecting interventions. Research reveals that combining practices and strategies within a single framework is a powerful method for achieving efficient and effective results for students (Chard, Harn, & Sugai, 2008).

Citations

Bellon, J. J., Bellon, E. C., & Blank, M. A. (1991). Teaching from a research knowledge base: A development and renewal process (Facsimile ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bennett, R. E. (2011). Formative assessment: A critical review. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(1), 5–25.

Borman, G. D., Hewes, G. M., Overman, L. T., & Brown, S. (2003). Comprehensive school reform and achievement: A meta-analysis. Review of educational research, 73(2), 125–230.

Celio, M. B., & Harvey, J. (2005). Buried treasure: Developing a management guide from mountains of school data. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Chard, D. J., Harn, B. A., Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2008). Core features of multi-tiered systems of reading and behavioral support. In C. R. Greenwood, T. R. Kratochwill, & M. Clemens (Eds.), Schoolwide prevention models: Lessons learned in elementary schools (pp. 31–58). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Chorpita, B. F., Becker, K. D., & Daleiden, E. L.. (2007). Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(5), 647–652.

Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., & Landrum, T. J. (Eds.). (2013). Evidence-based practices in learning and behavioral disabilities: The search for effective instruction (Vol. 26). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological bulletin, 52(4), 281–302.

Deming, W. E. (1966). Some theory of sampling. North Chelmsford, MA: Courier Corporation.

Detrich, R., Slocum, T. A., & Spencer, T. D. (2013). Evidence-based education and best available evidence: Decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. In B. G. Cook, M. Tankersley, & T. J. Landrum (Eds.), Evidence-based practices in learning and behavioral disabilities: The search for effective instruction (Vol. 26, pp. 21–44.). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (EHA), Pub. L. No. 94-142, 89 Stat. 773 (1975). (Codified as amended at 20 U.S.C. §§1400–1461, 1982).

Eldevik, S., Hastings, R. P., Hughes, J. C., Jahr, E., Eikeseth, S., & Cross, S. (2009). Meta-analysis of early intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38(3), 439–450.

Farley, A. J., Feaster, D., Schapmire, T. J., D’Ambrosio, J. G., Bruce, L. E., Oak, C. S., & Sar, B. K. (2009). The challenges of implementing evidence based practice: Ethical considerations in practice, education, policy, and research. Social Work and Society, 7(2), 246–259.

Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Horner, R., & Sugai, G. (2009). Readiness for change. Chapel Hill, NC: FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Naoom, S. F., & Wallace, F. (2009). Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice, 19, 531–540.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication #231). Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network.

Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (1986). Effects of systematic formative evaluation: A meta-analysis. Exceptional children, 53(3), 199–208.

Fuchs, D. & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly 41(1), 93–99.

Gardner, D. P. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. An open letter to the American people. A report to the nation and the secretary of education. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Gilbert, T. F. (1978). Human competence: Engineering worthy performance. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Gresham, F. (August, 2001). Responsiveness to intervention: An alternative approach to the identification of learning disabilities. Executive summary. Paper presented at the 2001 Learning Disabilities Summit: Building a Foundation for the Future, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED458755.pdf

Gresham, F. M. (2002). Responsiveness to intervention: An alternative approach to the identification of learning disabilities. In R. Bradley, L. Danielson, & D. P. Hallahan (Eds.), Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice (pp. 467–519). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gresham, F. (2007). Evolution of the response-to-intervention concept: Empirical foundations and recent developments. In S. B. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 10–24). New York, NY: Springer.

Grove, R. D., & Hetzel, A. M. (1968). Vital statistics rates in the United States, 1940-1960 (Public Health Services Publication 1677). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Hall, S. L. (Ed.). (2007). Implementing response to intervention: A principal's guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hallfors, D., & Godette, D. (2002). Will the “principles of effectiveness” improve prevention practice? Early findings from a diffusion study. Health Education Research, 17(4), 461–470.

Harlacher J., Sakelaris T., Kattelman N. (2014) Practitioner’s guide to curriculum-based evaluation in reading. New York, NY: Springer.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hintze, J. M., & Silberglitt, B. (2005). A longitudinal examination of the diagnostic accuracy and predictive validity of R-CBM and high-stakes testing. School Psychology Review, 34(3), 372–386.

Horn, W. F., & Packard, T. (1985). Early identification of learning problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(5), 597–607.

Hoyert, D. L., Kochanek, K. D., & Murphy, S. L. (1999). Deaths: final data for 1997. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics.

Jackson, P. W. (1990). Life in classrooms. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Jenkins, J. R. (2003, December). Candidate measures for screening at-risk students. Paper presented at the National Research Center on Learning Disabilities (NRCLD) Responsiveness-to-Intervention Symposium, Kansas City, MO. Retrieved from http://www.nrcld.org/symposium2003/jenkins/index. html.

Jenkins, J. R., Hudson, R. F., & Johnson, E. S. (2007). Screening for at-risk readers in a response to intervention framework. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 582–600.

Latham, G. I. (1988). The birth and death cycles of educational innovations. Principal, 68(1), 41–44.

Marsh, J. A., Pane, J. F., & Hamilton, L. S. (2006). Making sense of data-driven decision making in education: Evidence from recent RAND research. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Marturano, A., & Gosling J. (Eds.). (2008). Leadership: The key concepts. London, UK: Routledge.

Muñoz, R. F., Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1996). Institute of Medicine report on prevention of mental disorders: Summary and commentary. American Psychologist, 51(11), 1116–1122.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2015). NAEP Data Explorer. [Data file]. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/nde/)

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-110, § 115, Stat. 1425. (2002).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/

Riedel, B. W. (2007). The relation between DIBELS, reading comprehension, and vocabulary in urban first‐grade students. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(4), 546–567.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169.

Robinson, V. M., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674.

Rummler, G. A., & Brache, A. P. (1990). Improving performance: How to manage the white space on the organization chart. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Stoiber K. C., & Gettinger M. (2016) Multi-tiered systems of support and evidence-based practices. In S. B. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 121–141). New York, NY: Springer.

Sugai, G. (2013). Role of Leadership and culture in PBIS Implementation [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/pbisresources/PBIS_Implementation_leadership_braiding_apr_11_2013_HAND.pdf

Turnbull, A., Bohanon, H., Griggs, P., Wickham, D., Sailor, W., Freeman, R., ... & Warren, J. (2002). A blueprint for schoolwide positive behavior support: Implementation of three components. Exceptional Children, 68(3), 377–402.

U.S. Department of Education (2017). States granted waivers from No Child Left Behind allowed to reapply for renewal for 2014 and 2015 school years. Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/states-granted-waivers-no-child-left-behind-allowed-reapply-renewal-2014-and-2015-school-years

Vaughn, S., & Fuchs, L. S. (2003). Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: The promise and potential problems. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 18(3), 137–146.

Wayman, J. C., Midgley, S., & Stringfield, S. (2006). Leadership for data-based decision-making: Collaborative educator teams. In A. Danzig, K. Borman, B. Jones, & B. Wright (Eds.), Learner centered leadership: Research, policy, and practice, (pp. 189–206). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wayman, M., Wallace, T., Wiley, H. I., Tichá, R., & Espin, C. A. (2007). Literature synthesis on curriculum-based measurement in reading. Journal of Special Education, 41(2), 85–120.

Wing Institute. (2017). 2007 Wing presentation Janet Twyman [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://www.winginstitute.org/2007-Wing-Presentation-Janet-Twyman.

Yeh, S. S. (2007). The cost-effectiveness of five policies for improving student achievement. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(4), 416–436.