Teacher Retention Overview

Teacher Retention PDF

Donley, J., Detrich, R, Keyworth, R., & States, J. (2019). Teacher Retention. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-teachers-retention

Research has consistently demonstrated that classroom teachers have the strongest influence on students’ educational outcomes (Coleman et al., 1966; Hanushek & Rivken, 2006), including both short- and long-term academic (Chetty, Freidman, & Rockoff, 2014; Lee, 2018) and noncognitive outcomes such as motivation, self-efficacy, etc. (Jackson, 2018). Research also suggests that economically disadvantaged students are more likely than their advantaged peers to have less experienced and lower quality teachers (Clotfelter, Ladd, Vigdor, & Wheeler, 2006; Goldhaber, Lavery, & Theobald, 2015; Goldhaber, Quince, & Theobald, 2018; Kalogrides & Loeb, 2013). Issues with teacher attrition, recruitment problems, and fewer students choosing a teaching career have resulted in a short supply of qualified teachers in certain locations (e.g., high-poverty urban and rural communities), in particular subject areas (e.g., science, technology, engineering, and math [STEM] courses) and among certain student groups (e.g. special education students) (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2019). These issues have led to the inequitable distribution of high-quality teachers and poor outcomes for the students most in need of consistent high-quality instruction (Goldhaber, Gross, & Player, 2010; Goldhaber, et al., 2015; Goldhaber, Gross, & Player, 2010; Hanushek, Kain, & Rivken, 2004).

Keeping effective teachers in classrooms is, therefore, of great importance to ensure positive and equitable student outcomes. This research overview documents recent U.S. teacher shortages and retention data, reviews the factors that predict the likelihood of teachers staying in the classroom, and discusses the research support for addressing relevant issues and interventions that seek to improve teacher retention.

The Problem of Teacher Shortages

While teacher shortages have been the subject of recent media reports in nearly every U.S. state, the issue is not new and has been documented throughout the country’s history (Behrstock-Sherratt, 2016). For example, reports of shortages of math and science teachers first surfaced in the 1950s, and severe shortages of special education teachers have been documented since the 1960s (Ingersoll & Perda, 2010; U.S. Department of Postsecondary Education, 2017). While current teacher shortages are not occurring nationwide and, in fact, the teaching force overall has ballooned (Ingersoll, Merrill, Stuckey, & Collins, 2018) with only half of education graduates hired in a given year (Cowan, Goldhaber, Hayes, & Theobald, 2016), significant shortages of certified teachers in certain subject areas such as STEM and in many districts, especially rural and disadvantaged urban ones, exist across the country.

These shortages are projected to continue and even worsen in the future as demand increases and supply decreases (Sutcher et al., 2019). Expected increases in public school enrollment, teacher retirements, and preretirement attrition, together with reductions in student-teacher ratios and new teachers entering the profession, will likely create the demand for additional teachers (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Hussar & Bailey, 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Sutcher et al., 2019). Several factors influence teacher supply, including the varying ability of labor markets across the country to attract teachers (Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2005), offer salary and wage competitiveness (Adamson & Darling-Hammond, 2012; Baker, Farrie, & Sciarra, 2016), and provide positive teacher working conditions that lower attrition rates (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Kraft, Marinell, & Yee, 2016; Ladd, 2011).

In a comprehensive review and analysis of available supply and demand data, Sutcher et al. (2019) attributed the source of shortages to four factors: 1) decline in enrollment in teacher preparation programs (Dee & Goldhaber, 2017); (2) efforts to increase K–12 course offerings back to levels seen prior to the Great Recession (2007–2009), when substantial numbers of teachers were laid off ; (3) increases in student enrollment; and, (4) continuing high rates of teacher attrition. Sutcher et al. (2019) and others (e.g., Cowan, Goldhaber, Hayes, et al., 2016; Goldhaber, Krieg, Theobald, & Brown, 2015; Ingersoll, 2001, 2003; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Ingersoll & May, 2012; Ingersoll & Perda, 2010) argue that teacher turnover is a highly significant factor in the staffing shortages that plague many schools and districts throughout the country. Fully understanding the problem of teacher turnover and its consequences is the focus of the following section of this report.

Understanding the Importance of Teacher Retention

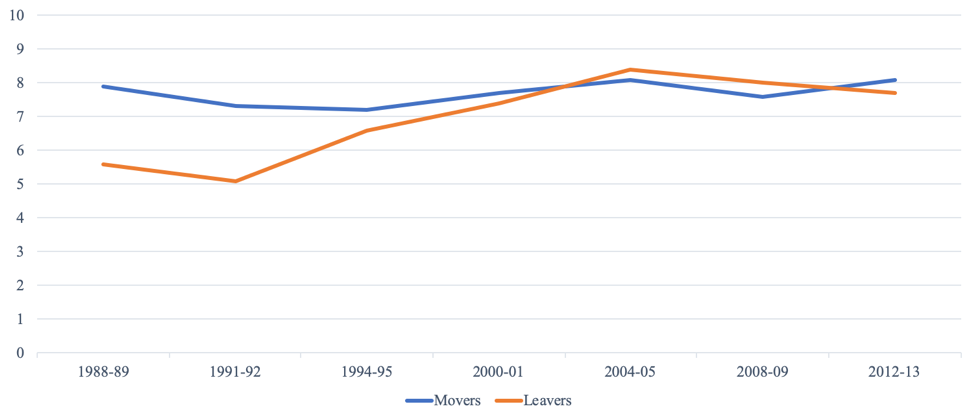

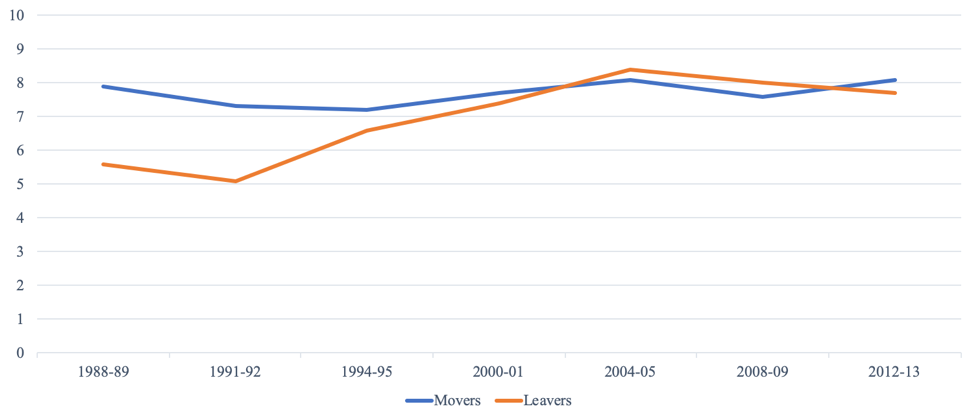

The Problem of Teacher Turnover and Attrition.Teacher turnover, defined as “change in teachers from one year to the next in a particular school setting” (Sorenson & Ladd, 2018, p. 1), has been a persistent problem often described as a revolving door in the teaching profession (Ingersoll, 2003). Teacher turnover includes teachers who move to a different school (“movers”) and those who either leave the profession to retire or leave voluntarily prior to retirement (“leavers”) (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Movers and leavers together represent the degree of “churn” in the teacher workforce (Atteberry, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2017; Ingersoll et al., 2018), while leavers considered separately represent the rate of attrition in the workforce. Rates of churn vary greatly across states, districts, and schools, and across subject areas and student populations (Redding & Henry, 2018). Figure 1 shows that teacher turnover rates in the United States have hovered around 16% over the last 10 years; this percentage includes both movers (8%) and leavers (8%) (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014). When broken out by school classification, rates of turnover were higher at charter schools (10.2% movers, 8.2% leavers), than at traditional public schools (8.0% movers, 7.7% leavers) (Goldring et al., 2014); these findings are consistent with other research showing higher charter school turnover rates (Gross & DeArmond, 2010; Stuit & Smith, 2010).

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey” (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014).

Figure 1. Percentage of public school teacher movers and leavers, 1988–1989 through 2012–2013

Figure 1 shows that while the percentage of movers has remained fairly consistent across 25 years of the study, the percentage of leavers increased substantially during this time period, suggesting increasing problems with attrition. In fact, an additional analysis of the sources of turnover from 2011–2012 to 2012–2013, using the most recent data available, found that of teachers who left, 14% left involuntarily (due in part to higher layoff rates caused by the Great Recession), 18% retired, 37% voluntarily moved to another school, and 30% were voluntary preretirement leavers; therefore, voluntary preretirement turnover represented two thirds of the turnover rate during these years (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Research shows that the movement of teachers out of schools was not equally distributed across states, regions, and districts (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) found higher rates in the South, in Title I schools (particularly in math and science, and for alternatively certified teachers), in schools serving higher numbers of students of color, and among teachers of color working in schools with higher turnover rates. The rates of turnover have been highest in economically disadvantaged and high-minority urban (Papay, Bacher-Hicks, Page, & Marnell, 2017) and rural schools (Sutton, Bausmith, O’Connor, Pae, & Payne, 2014), and the rates of mobility (movers) have often reflected an annual disproportionate shuffling from more to less disadvantaged schools, from high- to low-minority schools, and from urban to suburban schools (Ingersoll & May, 2012). While attrition due to retirement is predictable and has increased as the teacher workforce ages (Ingersoll et al., 2018), the relatively high preretirement attrition rate is a cause for concern. Attrition rates that have persistently hovered around 8% over the past 10 years in the United States compare unfavorably with those in high-performing countries such as Finland and Singapore, which typically average rates between 3% and 4% (Loeb, Darling-Hammond, & Luczak, 2005; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017).

While most research has focused attention on end-of-year teacher turnover, some studies have addressed teacher turnover duringthe school year (Redding & Henry, 2018, 2019). An analysis of turnover data in North Carolina showed that an average of 4.64% of teachers turned over during the school year, accounting for one quarter of the total turnover volume (Redding & Henry, 2018). Within-year turnover contributes to the workforce churn generated by end-of-year turnover and to the negative outcomes discussed later in this overview.

The Consequences of Failing to Retain Teachers.Teacher shortages are often a consequence of high attrition rates, as noted earlier; these shortages in turn commonly lead to inequitable distributions of quality teachers across schools and, not surprisingly, inequitable student outcomes, also as noted earlier. For example, many studies show that districts with more disadvantaged students have higher teacher attrition rates, translating into the need to hire additional teachers each year and a considerable degree of churn in the workforce (e.g., Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldhaber et al. 2010; Hanushek et al., 2004). High turnover in these schools often translates into fewer qualified and experienced teachers, placing students at a great learning disadvantage (Kini & Podolsky, 2016).

When teachers leave a school, they take along their knowledge and expertise in instructional strategies, collaborative relationships with colleagues, professional development training, and understanding of students’ learning needs at the school. High rates of teacher turnover and attrition disrupt the continuity of students’ learning experiences, staff collegiality and cohesion, and school operations and organizational cultures (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010; Ingersoll, 2001; Simon & Johnson, 2015). High turnover rates can serve as a barrier to the teacher collaboration that is essential for instructional improvement (Guin, 2004). Ronfeldt, Loeb, & Wyckoff (2013) found that teacher turnover in New York City elementary schools reduced standardized test performance for students whose teachers left as well as students whose teachers remained at the school. Hanushek, Rivkin, & Schiman (2016) similarly found reduced student achievement as a result of teacher turnover in low-achieving but not higher achieving schools. Turnover that occurs withinthe school year has recently been shown to be of particular concern for the disruption of student learning, accounting for approximately one quarter of all turnover (Redding & Henry, 2018). This type of turnover can result in classroom disruption, staff instability, and changes to teacher quality, all of which can combine to negatively impact student learning and achievement (Henry & Redding, in press). Within-year turnover has been shown to produce lower levels of elementary and middle school student achievement in reading and math, particularly when it occurs after the first semester and closer to the end of the school year (Henry & Redding, in press). Schools with higher proportions of minority and economically disadvantaged students are more likely to experience within-year turnover (Redding & Henry, 2018), making a collaborative work environment difficult and resulting in insufficient resources to mentor the large numbers of new teachers who enter during the school year (Simon & Johnson, 2015).

The research literature on the impact of turnover on teacher quality is mixed, with studies that used value-added measures of teacher effectiveness finding that teachers who exited were less able than those who stayed (e.g., Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, Ronfeldt, & Wyckoff, 2010; Hanushek & Rivken, 2007), suggesting that workforce composition in some cases may improve as a result of turnover. Feng and Sass (2017) found that top quartile and bottom quartile teachers (based on value-added teacher effectiveness data) left their schools at higher rates than teachers rated average, and that the likelihood of teachers moving to other district schools decreased as the share of experienced and highly qualified teachers increased within a school. Therefore, it is equally important to understand the quality of teachers who replace those who leave (Hanushek et al., 2016). In studying the long-term impacts of teacher turnover on the composition of teachers in North Carolina middle schools, Sorensen and Ladd (2018) found that turnover from the 1990s to 2016 increased a school’s portion of teachers lacking full licensure and teachers with fewer years of experience, with the strongest effects found for economically disadvantaged schools. Such schools frequently have difficulty recruiting high-quality teachers (Dee & Goldhaber, 2017), and improvements to retention will likely require improved recruiting tools and practices (Wronowski, 2018).

Teacher turnover is also quite costly, with more than $7 billion spent annually on separation, recruitment, hiring, and induction and training that otherwise could be used for academic programs and services (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2014; Barnes, Crowe, & Schaefer, 2007; Darling-Hammond & Sykes, 2003; Sorenson & Ladd, 2018). Teacher replacement costs range from $9,000 per teacher in rural districts to more than $20,000 per teacher in urban districts (Barnes et al., 2007). One study found that district costs per year for teacher turnover ranged from $3.2 million to $5.6 million, with the higher costs in urban districts that frequently have higher turnover rates (Synar & Maiden, 2012). Not easily calculated are the costs resulting from a loss in productivity when a more experienced teacher is replaced by a less experienced or less qualified one (Watlington, Shockley, Guglielmino, & Felsher, 2010).

It is important to note that, in some cases, teacher turnover may result in benefits for students, schools, and districts. For example, some within-year turnover is due to supportive parental and medical leave policies that make it possible for teachers to temporarily exit for family considerations and return to the school, thus defraying the costs of recruiting new teachers (Papay et al., 2017). As noted earlier, it is also possible that teacher exits due to extremely poor performance can benefit the composition of the teaching workforce and student learning, if low-performing teachers are replaced with more effective ones. In a study of the District of Columbia Public School (DCPS) system, Adnot, Dee, Katz, and Wyckoff (2017) found that using a teacher evaluation and compensation system that moved ineffective teachers out of schools and provided financial and nonfinancial rewards to highly effective teachers who remained was beneficial both to the overall effectiveness of the teaching workforce and to student achievement. Cullen, Koedel, & Parsons (2016) found that a teacher evaluation system increased the exit rate for low-performing teachers, but the changes to workforce composition were not large enough to improve student achievement, a finding the authors attributed in part to the lack of a financial reward system for high-performing teachers like the one used in the DCPS system.

While some positive benefits to teacher turnover have been identified, in general the failure to retain teachers has a negative impact on students and schools. Understanding the factors that influence teacher retention can illuminate potential strategies for enhancing the likelihood that effective teachers remain in their classrooms.

Factors Related to Teacher Turnover and Retention

Research has documented a number of factors that are related to teachers’ decisions to leave or remain in their schools. Certain demographic characteristics, level of teaching experience, qualifications, and teaching area can predict the likelihood of turnover. In addition, school contextual factors and teacher working conditions influence teachers’ decisions to remain in their schools. A discussion of important predictors of teacher retention follows.

Teacher Characteristics and Qualifications.The exit of teachers from schools is not uniformly spread across different teacher characteristics and qualifications. While women represent the majority of teachers, particularly at the elementary level (Ingersoll et al., 2018), they are also more likely to leave teaching than men due to a variety of factors such as childbearing and better opportunities in other workforce sectors (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014).

While significantly more ethnic/racial minority teachers have entered the workforce in recent years due in part to minority recruitment programs, just 20% of teachers are minorities compared with more than half of the student population (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Most of the increase in minority teachers has occurred in high-poverty, hard-to-staff schools (Ingersoll & Merrill, 2017); however, the turnover rate among minority teachers has also increased by 45% in recent years (Ingersoll, May, & Collins, 2017) and exceeds that of white teachers (Goldring et al., 2014). Research by Ingersoll and colleagues (2017) found larger gaps between minority and white teacher movers than leavers, and the data suggested that the difficult working conditions in many hard-to-staff schools were responsible for the higher rates of minority teacher turnover. Minority teacher turnover in these schools may be particularly problematic given research that suggests positive academic and behavioral benefits for minority students assigned to teachers of the same ethnicity (Redding, 2019).

Research shows that beginning teachers have the highest turnover rate of any teacher group (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll, 2003; Papay et al., 2017), with recent national data showing that more than 44% of new teachers exit within 5 years (Ingersoll et al., 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Raue & Gray, 2015). Papay and colleagues (2017) reported even higher turnover rates in a study on urban schools, with early career attrition rates ranging from 46% to 71% depending on the district. Nationally, nearly two thirds of the turnover among beginning teachers occurs within the first 3 years of teaching (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Most of this turnover is voluntary (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017) and includes moving to a different school, leaving teaching temporarily, or leaving the profession permanently. When asked for their reasons for exit, roughly one third of first-year teachers indicated their exit was due to involuntary staffing changes, 40% indicated that family or personal issues were important, 32% left to pursue another job or career, and 44% left due to dissatisfaction with their position (respondents could report more than one reason for their exit) (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Involuntary transfer or dismissal has frequently targeted early-career teachers, with personnel decisions focused on “last in, first out” policies to determine which teachers to discharge (Kraft, 2015).

Working conditions likely explain a large portion of turnover for all teachers, but particularly for beginning teachers, who are adjusting to the profession and their school context (Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Simon & Johnson, 2015). Some evidence suggests that quality mentoring and induction programs can provide supportive structures for new teachers that increase their chances of being retained (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011; Raue & Gray, 2015). Unfortunately, research shows that many teachers in high-poverty schools do not have mentors, and even those who do have them are less likely to report meaningful interactions about their instruction, partially because their mentors often teach different grades or subjects, or do not teach at the same school (Donaldson & Johnson, 2010).

A teacher’s qualifications and entry pathway into the profession also predict the likelihood of turnover. The percentage of teachers entering the profession from outside traditional, in-state university teacher preparation programs nearly doubled from 1999–2000 (13%) to 2011–2012 (25%) (Redding & Smith, 2016), in large part due to staffing shortages in hard-to-staff subjects and schools (Redding & Henry, 2019). Research shows that, even after controlling for factors that predict high turnover, alternatively certified teachers are still more likely than traditionally prepared teachers to exit the profession (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Boyd et al., 2012; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Redding & Smith, 2016). Alternatively certified teachers are more likely to work in urban schools in disadvantaged communities, where working conditions are often less than optimal (Cohen-Vogle & Smith, 2007), with less preparation and support than for traditionally certified teachers (Redding & Smith, 2016). Combining teaching and coursework for certification likely is overwhelming and contributes to the difficult professional situation for these teachers (Redding & Henry, 2019). Some evidence also suggests higher turnover rates for teachers prepared in out-of-state as compared with in-state preparation programs (Bastian & Henry, 2015).

Teaching Area.Results from analyses of teacher attrition and mobility suggest that elementary and humanities teachers have among the lowest turnover rates, and teachers of math, science, special education, and English for foreign language speakers have significantly higher rates (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). Math and science teachers are significantly more likely to leave high-minority, high-poverty, and Title I schools than their counterparts teaching math and science in other types of schools (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Ingersoll & May, 2012). As many as 30% of math and science teachers in schools with large numbers of students of color are alternatively certified, compared with just 12% of those in schools with mostly White students (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). This is concerning as many alternative certification pathways lack important coursework and student teaching experiences, which can stymie beginning teachers’ performance and ultimately lead to higher turnover rates (Redding & Henry, 2019). Relatively high turnover rates among math and science teachers in high-need schools contribute to shortages in these schools in both urban and rural areas (Goldhaber, Krieg et al., 2015; Player, 2015).

Teacher shortages in special education represent the largest shortages in 48 of the 50 states (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016). They are due to insufficient numbers of special education teachers being prepared and to high numbers leaving their positions. Special education teachers have higher average turnover rates than general education teachers, particularly during the early career years (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Vittek, 2015). While no differences in turnover have been found for special education teachers in Title I versus non-Title I schools, rates are considerably higher in high-minority than low-minority schools (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Special education teachers are likely to face difficult working conditions, such as excessive paperwork, lack of collaboration with colleagues, lack of appropriate induction/mentoring, and lack of administrative support, all of which increase the likelihood that these teachers will transfer to a general education position or leave teaching entirely (Boe, Cook, & Sunderland, 2008; McLesky, Tyler, & Flippin, 2004; Vittek, 2015). Recent research by Gilmour and Wehby (in press) has also found that as the proportion of students with disabilities increases in the classrooms of general education teachers, the likelihood of turnover increases; teaching students with emotional/behavioral disabilities is related to increased turnover rates of not just special education teachers but also general education teachers.

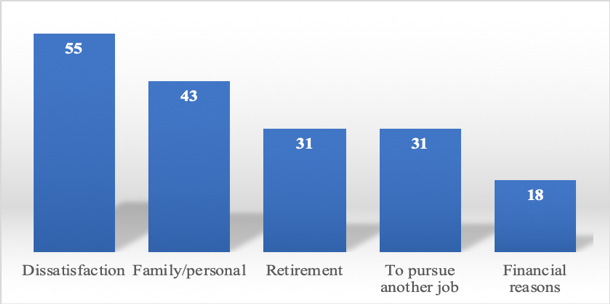

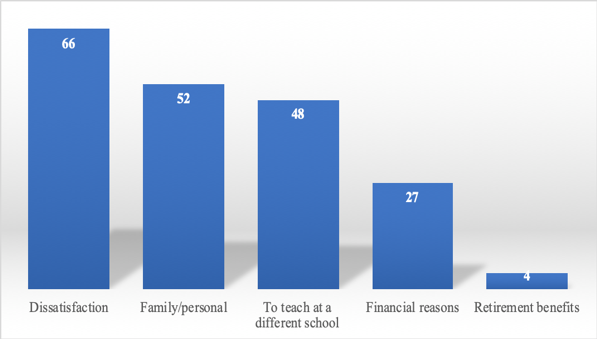

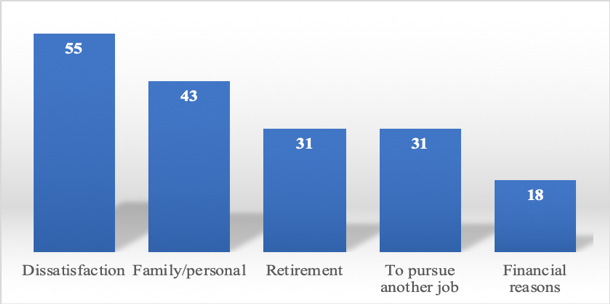

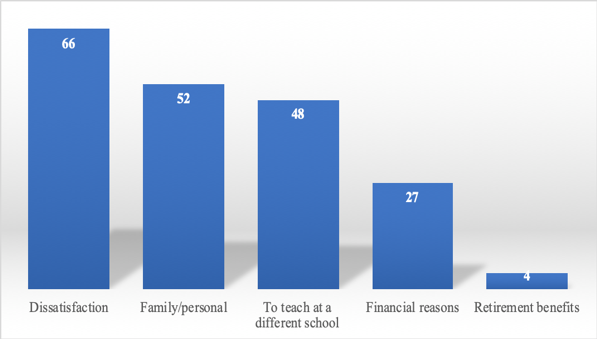

Reasons for Teacher Turnover.Ascertaining the reasons for teacher turnover provides important information for understanding the relevant factors in teachers’ decisions to leave. Recent data illustrate the factors that teachers report as very important in their decision to leave the teaching profession (Figure 2) or to move to a different school (Figure 3) (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017).

Adapted from Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond (2017). Figure displays percentages of teachers reporting each factor as important; teachers were able to select more than one reason, so percentages do not total 100.

Figure 2. Factors important in teachers leaving the profession

Adapted from Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond (2017). Figure displays percentages of teachers reporting each factor as important; teachers were able to select more than one reason, so percentages do not total 100.

Figure 3. Factors important in teachers moving to another school

Dissatisfaction was most frequently cited by both movers and leavers as important in their decision to leave. Leavers most frequently cited testing/accountability (25%), problems with administration (21%), and dissatisfaction with teaching as a career (21%) as sources of dissatisfaction; the family/personal reasons they cited included moving to a more conveniently located job, health reasons, and caring for family members. Two thirds of movers reported dissatisfaction as a reason to move, citing concerns with school administration, lack of influence on school decision making, and school conditions such as facilities and resources (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond’s 2019 research also found that a perceived lack of administrative support and compensation were significantly related to turnover. These findings highlight the importance of working conditions in teacher retention.

Teacher Working Conditions.Working conditions are an important predictor of teacher turnover (e.g., Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Johnson, Kraft, & Papay, 2012). Research has demonstrated that student demographics are important in teachers’ decisions to remain at their schools and that they most often leave schools containing large numbers of low-income, low-achieving, and minority students (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Clotfelter et al., 2006; Hanushek et al., 2004). However, teacher interviews have revealed that dysfunctional school contexts that make it difficult to succeed with these student populations, rather than the students themselves, are responsible for the decision to leave (Allensworth, Ponisciak, & Mazzeo, 2009; Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Johnson et al., 2012). In fact, several studies have demonstrated that teacher working conditions explain most of the relationship between student demographics and teacher turnover (Allensworth et al., 2009; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Ladd, 2011; Simon & Johnson, 2015).

A critical aspect of teacher working conditions that influences retention is the quality of principal leadership (Boyd et al., 2011; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Johnson et al., 2012; Ladd, 2011; Marinell & Coca, 2013). Research shows that as school leadership improves, the likelihood of teacher turnover decreases (Kraft, Marinell, & Shen-Wei, Marinell, & Shen-Wei Yee, 2016; Ladd, 2011). For example, teachers were more likely to stay at schools where they reported the principal was trusting and supportive of teachers, a knowledgeable instructional leader, an efficient manager, and skilled at forming external partnerships with external organizations (Marinell & Coca, 2013). Additional research shows that teachers who left schools led by the most effective principals were less likely to be effective than those who left schools led by less successful principals (Branch, Hanushek, & Rivken, 2013). Unfortunately, high-poverty schools are often staffed with less experienced and weaker principals (Loeb, Kalogrides, & Horng, 2010); on a positive note, research has also shown that an effective principal may offset teacher turnover in disadvantaged schools (Grissom, 2011; Kraft et al., 2016).

Additional teacher working conditions that have been identified as important to teacher retention (and that are related to administrative leadership) include a sense of collective responsibility for student outcomes, a sense of collegiality and trusting working relationships, a sense of safety and discipline in the school, parent-teacher interaction, time for collaboration and planning, and expanded roles for teachers (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Kraft et al., 2016; Simon & Johnson, 2015). Simon and Johnson cited three factors supporting teachers’ work with their colleagues: (1) an inclusive environment of respect and trust (e.g., teachers respect one another and trust that their colleagues are “doing the right thing for the right reasons”); (2) formal structures for collaboration and support (e.g., well-designed induction/mentoring programs and well-designed instructional teams or professional learning communities, or PLCs); and (3) a shared set of professional goals and purposes (e.g., all teachers share a social justice perspective and are motivated to help disadvantaged students achieve). The research literature also suggests that professional empowerment and opportunities for autonomy and shared decision making are important (Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll, 2003; Ingersoll & May, 2012; Marinell & Coca, 2013; Wronowski, 2018). Goldring et al. (2014) found that of teachers who left the profession, more than half indicated they had more autonomy in their work and greater influence over workplace practices and policies in their current job than they did as teachers. Inadequate autonomy and empowerment may be particularly important for minority teachers teaching in hard-to-staff schools as well as responsible for many of these teachers leaving the profession and subsequent teacher shortages (Ingersoll & May, 2012 Ingersoll et al., 2017). In addition, research has ascribed higher teacher attrition to a perceived lack of influence and autonomy in the school, and few opportunities for career advancement and career pathways (Ingersoll & Perda, 2010; TNTP, 2012), suggesting that leadership opportunities may encourage many teachers to stay. A recent study found that two thirds of national and state “teacher of the year” award winners rated teacher leadership opportunities as a top growth experience that contributed positively to their career progression (Behrstock-Sherratt, Bassett, Olson, & Jacques, 2014).

A related aspect of teacher working conditions that influences retention is the level of compensation. Teacher salaries are generally not competitive with other labor markets (Hanushek, Piopiunik, & Wiederhold, 2014), even when controlling for the shorter work year, with new teachers earning approximately 18% less than individuals working in other fields, and midcareer teachers earning 30% less (Baker, Sciarra, & Farrie, 2015, 2018). Research consistently shows that teachers who work in districts that pay less are more likely to leave their jobs (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019; Goldring et al., 2014; Podolsky, Kini, Bishop, & Darling-Hammond, 2016). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) found a significant relationship between the highest teacher salary possible in a district and turnover; for example, teachers who could earn more than $78,000 in their districts had an attrition rate 31% lower than those who could earn a maximum of only $60,000. Gray & Taie (2015) found a 10-point percentage gap in turnover rates between novice teachers whose first-year salary was $40,000 or higher compared with beginning teachers earning less. Whether math and science and other in-demand teachers decide to remain in teaching is particularly dependent on salary (Adamson & Darling-Hammond, 2011).

Research further indicates the highest paid teachers in high-poverty schools are paid significantly less than the highest paid teachers in less disadvantaged communities (Adamson & Darling-Hammond, 2011). The inability to adequately reward excellent teachers contributes to an inequitable distribution of high-quality teachers among schools within districts, as teachers with more seniority transfer out of less desirable placements and are replaced by less experienced and often less effective teachers (Podgursky & Springer, 2011). Many educational researchers and policymakers are advocating for reforms to the compensation teachers receive, particularly in hard-to-staff subjects and schools (Aragon, 2016; Dee & Goldhaber, 2017; Sutcher et al., 2016).

The factors that predict turnover and retention cited above (teacher demographics and teaching areas, qualifications, and working conditions) suggest where improved policies and programs can support better rates of teacher retention, particularly for schools within high-need communities. An overview of policies and programs that have received research support in the literature is provided below; where available, relevant cost-benefit research on these initiatives is included in the discussion.

Research-Based Strategies for Improving Teacher Retention

Strategies to Improve Compensation.As described earlier, teacher salary is an important predictor of retention. Competitive and equitable salaries as well as other incentives such as housing and child-care supports and forgivable loans and service scholarships can serve to attract and retain teachers in high-need fields and locations (Podolsky, Kini, Darling-Hammond, & Bishop, 2019; Sutcher et al., 2016). The previously cited District of Columbia’s performance pay system, which provides teacher supports in high-needs schools, has been shown to effectively remove low-performing teachers, recruit and retain high-performing teachers, and improve student achievement (Adnot et al., 2017).

The Florida Critical Teacher Shortage program provided student loan forgiveness to teachers in designated shortage areas, compensated those seeking certification in the shortage areas with paid tuition, and gave single year bonuses to those already certified and teaching in shortage areas. In a 2015 study, Feng and Sass found that the loan forgiveness program and one-time retention bonus resulted in decreased teacher attrition of math, science, foreign language and ESOL teachers, and of special education teachers receiving larger payments; in addition, the tuition reimbursement program increased the likelihood a teacher would become newly certified in a high-need area. This finding is consistent with other studies that found that providing bonuses to effective teachers already teaching in high-poverty or low-achieving schools can lead to reductions in teacher attrition (Clotfelter, Glennie, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2008; Springer, Swain, & Rodriguez, 2016; Swain, Rodriguez, & Springer, 2019) and may represent a cost-effective approach. Clotfelter and colleagues found that bonus payments reduced teacher attrition rates by 17% in hard-to-staff subjects in disadvantaged and/or low-performing schools during the 3 years of the bonus program. Springer et al (2016) reported that a $5,000 bonus for high-performing teachers working in high-need schools in Tennessee improved retention in tested grades and subjects by 20% but did not impact the retention of other teachers who did not receive bonuses.

The Talent Transfer Initiative (TTI) offered a substantial financial incentive ($20,000 over 2 years) to encourage highly effective teachers in a North Carolina district to transfer to the lowest performing schools (Glazerman, Protik, Teh, Bruch, & Max, 2013). This initiative succeeded in attracting high-performing (based on value-added data) teachers to fill the vacancies in these schools and was associated with increased retention rates during the 2-year bonus period. However, turnover increased substantially after the bonus program, and no retention differences were found between bonus and non-bonus recipients after the program ended.

Late-career financial incentives are also recommended by some researchers, as the teaching profession has a greater percentage of early retirees than other professions (Dee & Goldhaber, 2017; Harris & Adams, 2007). Some research has suggested that targeted retention bonuses for highly effective senior teachers or those teaching in STEM fields may add anywhere from 3 to 8 years to their careers, and may be a useful tool for raising teacher workforce quality and closing achievement gaps if bonuses are targeted at high-poverty schools (Kim, Koedel, Ni, Podgursky, & Wu, 2016). In addition, neutralizing “push” incentives that encourage early retirement through retention bonuses selectively targeted at the most effective teachers may offer a cost-effective way to achieve intended outcomes (Kim, Koedel, Ni, Podgursky, & Wu, 2017).

Researchers agree that, to ensure incentive programs are cost-effective, districts must target financial incentives at teachers in hard-to-staff schools and who have demonstrated positive impacts on student achievement (Dee & Goldhaber, 2017; Sutcher et al., 2016). In addition, financial incentive strategies are most effective and sustainable when paired with improvements to teachers’ working conditions (Aragon, 2016).

Strategies to Improve Teacher Preparation.The research suggests that retention and recruiting, particularly in high-needs fields, can be enhanced with well-designed programs that subsidize the costs of preparation (Feng & Sass, 2015; Podolsky & Kini, 2016). For example, the Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship Program funded through the National Science Foundation “seeks to encourage talented [STEM] majors and professionals to become K–12 mathematics and science (including engineering and computer science) teachers” (National Science Foundation, n.d.). Common components of the various programs include internships, scholarships, and support systems that are built into teacher preparation programs and extend into the early years of teaching (Kirchoff & Lawrenz, 2011; Ticknor, Gober, Howard, Shaw, & Mathis, 2017). Recipients reported that the scholarship influenced their commitment to teach in a high-needs school (Liou, Kirchoff, & Lawrenz, 2010), and the greater the scholarship amount relative to tuition costs, the more the scholarship influenced the decisions of recipients, especially non-Whites, to enter the teaching profession and teach in high-needs schools (Liou & Lawrenz, 2011).

Other research has shown that supportive peer networks are important in scholarship recipients’ decisions to remain in high-need schools beyond required time periods (Ticknor et al., 2017). The North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program recruits high-performing high school students to complete a teacher preparation program in exchange for a commitment to teach in the state for at least 4 years . Researchers found that teaching fellows had higher retention rates and were more effective than educators prepared in or out of state, alternative entry educators, or Teach for America teachers; in addition, three quarters of teaching fellows returned for an additional year beyond their program commitment (Henry, Bastian, & Smith, 2012).

Teacher residencies provide another research-based strategy for enhancing the likelihood of preparing and retaining effective teachers. While many alternative certification programs require teachers to train while teaching in order to earn income, teacher residency models fund preparation costs for candidates while allowing for a full preparation year before employment (Guha, Hyler, & Darling-Hammond, 2016). These programs “place candidates who plan to teach in shortage fields and who want to commit to high-need urban or rural schools into paid year-long apprenticeships with expert mentor teachers, while they complete tightly linked credential coursework and earn a master’s degree from partnering universities” (Sutcher et al., 2016, p. 63). Program participants continue to receive mentoring while they teach, and pledge to spend a minimum of 3 to 5 years in the district’s schools. Emerging research suggests that teacher residency program graduates have higher levels of retention than their nonresidency peers, with 80% to 90% remaining as teachers within the district after 3 years, and 70% to 80% remaining after 5 years (Guha et al., 2016; Papay, West, Fullerton, & Kane, 2012; Silva, McKie, & Gleason, 2015).

Grow Your Own (GYO) programs have been proposed as potential solutions to systemic teacher shortages and, in some cases, to increase teacher diversity in urban and isolated rural schools. GYO programs capitalize on the fact that many young teachers have a strong preference to teach close to home, and they establish career pathways or pipelines for candidates who are committed specifically to teach in these environments (Boyd et al., 2005; Reininger, 2012). GYO programs can be implemented at the high school level through cadet programs and teaching academies, and many programs also recruit and support community members, paraprofessionals, and teachers’ aides in earning a teaching credential (Sutcher et al., 2016). These programs, which increasingly receive attention in the research literature, are widely touted as avenues to increase diversity and staff hard-to-staff subjects and schools in both urban and rural settings. Some research has demonstrated high retention rates for teachers participating in various types of programs (Gist, Bianco, & Lynn, 2019), including paraprofessional (Abramovitz & D’Amico, 2011; Clewell & Villegas, 2001), and teacher assistant pipeline programs (Fortner, Kershaw, Bastian & Lynn, 2015). For example, Ross and Ahmed (2016) demonstrated long-term (10 to 15 years) retention rates for a community-focused immigrant teacher pipeline program.

Strategies to Improve Teacher Induction and Support.Research indicates high turnover rates within the first 5 years of teaching, particularly when teachers lack supportive school structures to develop their expertise. Most states and districts have developed induction programs for new teachers to provide a “bridge from student of teaching to teacher of students” (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011, p. 203). These programs provide a range of supports that include mentoring by experienced teachers, workshops, common planning time with experienced colleagues, and reduced course loads. Wood and Stanulis (2009) stated that a quality teacher induction program “enhances teacher learning through a multi-faceted, multi-year system of planned and structured activities that support novice teachers’ developmentally-appropriate professional development in their first through third year of teaching” (p. 3). Induction programs and mentoring components in particular have been consistently found to positively impact teacher retention (Bastian & Marks, 2017; Raue & Gray, 2015). Stronger effects, however, have been found for induction programs providing teachers with mentors from their own subject area, and for induction programs that allow for common planning or collaboration time with other colleagues teaching in the mentee’s subject area (Ingersoll, 2012). Ingersoll also found that the more comprehensive the induction package, the greater the benefits to reducing teacher attrition.

Comprehensive induction programs that contribute to improved teacher working conditions may be especially crucial for high-poverty, low-performing schools, which often have a greater number of newer, less experienced teachers who tend to be the most likely to leave the profession (Simon & Johnson, 2015). High-quality induction programs may be a cost-effective approach for schools and districts. One study found that after 5 years of a comprehensive 2-year induction program, the cost of $13,500 yielded $21,500 in benefits (including lower turnover and consequently lower recruiting costs) (Villar & Strong, 2007). See Wood and Stanulis (2009) for a review of the induction literature and quality program components.

Strategies toImprove Leadership and Career Advancement Opportunities.While there is little in the research literature that directly links retention to increased leadership opportunities, the research cited previously on dissatisfaction and turnover suggests that a lack of autonomy and few opportunities for professional advancement factor into teachers’ decisions to leave (Ingersoll & Perda, 2010; TNTP, 2012). Some research suggests that allocating incentives or leadership responsibilities based on attainment of National Board Certification, which has been associated with teacher effectiveness (Chingos & Peterson, 2011; Cowan & Goldhaber, 2016), may foster working conditions that allow for a meaningful career trajectory for high-quality teachers and can be a cost-effective way to retain them (Cowan & Goldhaber, 2016; Lawrence, 2015; Lawrence, Rallis, & Keller, 2014; Podolsky et al., 2016). Accomplished teachers who are given the chance to share their expertise by serving in teacher leadership roles (e.g., coaches, teacher educators, or mentors) may be less likely to leave the profession. Career advancement programs (e.g., career ladders) that offer increased compensation, responsibility, and recognition may attract larger numbers of high-quality teachers and keep them in the classroom (e.g., Natale, Gaddis, Bassett, & McKnight, 2013, 2016). Booker & Glazerman (2009) found that teachers in a career ladder program were significantly less likely to leave their districts or the teaching profession than teachers in noncareer ladder districts and were more likely to report increased job satisfaction.

The Opportunity Culture initiative provides a model to extend the reach of effective educators and sustainably fund teacher leader roles by exchanging current roles for new higher paid roles. Multi-classroom leadership involves highly effective teachers assuming a leadership role for a team of teachers along with accountability for student outcomes in the classrooms of team teachers. The multi-classroom leader (MCL) “becomes a mentor and instructional resource for all on the team, and leadership responsibilities include supervising instruction, evaluating and developing teachers’ skills, and facilitating team collaboration and planning” (Backes & Hansen, 2018, p. 5). Significant compensation is provided for these teacher leader roles, with MCLs receiving stipends between $13,000 and $23,000 depending on the numbers of students and teachers reached (Natale et al., 2016). While the impact of this model on teacher retention is unknown, a recent evaluation of the initiative in three pilot school districts found that Opportunity Culture schools, and specifically the MCL model, significantly improved students’ math performance (Backes & Hansen, 2018). The researchers concluded that the intensive, personalized instructional coaching provided by the MCL model likely led to net overall improvements in teacher quality, which is consistent with research on the positive impact of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement (Kraft, Blazar, & Hogan, 2018).

Strategies to Improve Teacher Working Conditions.Research suggests that when the organizational contexts in which teachers work are enhanced, teachers are more likely to persist in their positions (Kraft et al., 2016). Working conditions have been described in the literature as a mediator in the relationship between teacher turnover and school demographic characteristics (Geiger & Pivovarova, 2018), and may be particularly important for minority teacher retention. As noted previously, principal leadership plays a large role in determining working conditions and strongly impacts teacher turnover, particularly in high-need schools (Grissom, 2011); school districts that struggle with teacher turnover must recruit principals who have the proven capacity to improve teacher working conditions (Burkhauser, 2017). Principals are charged with shaping the school’s vision, serving as instructional leaders, developing teachers’ leadership skills, managing people and processes, and ensuring a hospitable and safe school environment (Wallace Foundation, 2013). Some research demonstrates that high-quality principal preparation and development programs can increase principals’ effectiveness in retaining effective teachers. Providing principal professional development activities such as coaching and/or mentoring holds promise for improving principal practice and reducing teacher attrition (Jacob, Goddard, Kim, Miller, & Goddard, 2015; Lochmiller, 2013).

One research-based principal and teacher-leader development program is the McREL Balanced Leadership Program, designed to provide research-based guidance in the form of 21 key leadership responsibilities that help principals and other leaders become more effective and improve their capacity to enhance student achievement. A randomized control trial study of rural schools in Michigan showed that the program significantly reduced teacher turnover among both teachers participating in the program and colleagues who did not participate but worked at the same school (Jacob et al., 2015).

Teacher surveys or other assessments of working conditions can be used to determine the quality of the school working environment, and the data can be used to target improvements as necessary to foster higher levels of retention (Burkhauser, 2017; Kraft et al., 2016; Podolsky et al., 2019). For example, the Teaching, Empowering, Leading and Learning (TELL) Survey was used to garner support for statewide education initiatives (e.g., increased planning time and funding for professional learning) that could improve teacher working conditions in North Carolina (Burkhauser, 2017). Another study found that teachers’ survey responses to items addressing principal leadership, the school’s climate, and relationships with colleagues strongly predicted teacher satisfaction and plans to remain in teaching (Johnson et al., 2012).

Improved working conditions may also be fostered through targeted professional learning strategies and school redesign (Podolsky et al., 2019). Teachers need ample time for productive collaboration to plan, evaluate, and modify curricula (Simon & Johnson, 2015), and regular blocks of time that are built into the daily schedules of teachers teaching the same subject or who share groups of students may foster teacher retention. Redesigned high schools that incorporate additional time for teachers offer the potential for improved teacher working conditions and retention (Glennie, Mason, & Edmunds, 2016); however, research has yet to address this topic fully. In many cases, additional resources will be necessary to compensate teachers for professional learning that occurs outside their contract roles, or to hire additional staff to cover teachers’ classes during professional learning time (Podolsky et al., 2019).

Summary and Conclusions

Problems with teacher turnover contribute significantly to teacher shortages and result in the inequitable distribution of effective and qualified teachers across schools. The consequences of turnover are primarily negative; they include fewer effective teachers in disadvantaged, high-needs schools, disruptions to school operations and teacher collegiality, poorer student outcomes, and higher costs for districts. The research cited in this report suggests several common themes that predict teacher turnover and attrition. Teacher turnover is highest among minority teachers (particularly those working in high-needs schools), beginning teachers, alternatively certified teachers, special education teachers, and teachers of math, science, and English for foreign language speakers. The key reasons for turnover have centered primarily around dissatisfaction with the job or school due to poor working conditions, which are more predictive of turnover than student demographic characteristics. Principal leadership, teacher relationships and collaboration, a safe school climate, autonomy, shared decision making, and opportunities for leadership and advancement are all important components of teacher working conditions. In addition, compensation levels are predictive of turnover, with teachers (particularly those teaching hard-to-staff subjects or students) more likely to exit districts that pay less.

Several strategies for improving teacher retention have received support in the research. Improved compensation through competitive and equitable salary structures, incentives such as loan forgiveness and paid tuition for preparation, and, in certain cases, targeted bonuses for effective teachers can serve to attract and retain teachers in hard-to-staff subjects and schools. Working conditions may be improved through enhanced principal preparation and coaching/mentoring, assessing teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions to target improvements, and increasing opportunities for collaboration and professional learning. Combining financial incentives with initiatives to enhance teacher working conditions may be particularly effective; more research is needed to identify how best to design programs that combine incentives and improved working conditions.

Teacher residencies and Grow Your Own programs can also attract potential educators to hard-to-staff subjects and schools, enhancing their preparation and increasing their odds of being retained. Higher quality induction and mentoring approaches better prepare teachers for their roles and reduce teacher attrition, and offer a cost-effective way to improve retention. Providing a meaningful career trajectory for teachers through financial incentives linked to enhanced leadership opportunities and additional career paths in teaching are also linked to lower rates of turnover.

Finally, a note of caution: While many of the retention strategies highlighted in this report have research support, there are a number of implementation barriers that must be considered when evaluating their potential to enhance teacher retention. For example, while mentoring programs have been found to positively impact retention (Bastian & Marks, 2017), inadequate compensation may prevent the most effective teachers from being recruited into mentoring positions (Goldhaber, Krieg, Naito, & Theobald, 2019). These barriers are discussed more fully in the Teacher Retention Strategies report, also available on this site.

Citations

Abramovitz, M., & D’Amico, D. (2011). Triple payoff: The Leap to Teacher program. New York, NY: City University of New York Murphy Institute.

Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2011). Speaking of salaries: What it will take to get qualified, effective teachers in all communities. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/speaking-salaries-what-it-will-take-get-qualified-effective-teachers-all-communities.pdf

Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2012). Funding disparities and the inequitable distribution of teachers: Evaluating sources and solutions. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 20(37), 1–46.

Adnot, M., Dee, T., Katz, V., & Wyckoff, J. (2017). Teacher turnover, teacher quality, and student achievement in DCPS. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 54–76.

Allensworth, E., Ponisciak, S., & Mazzeo, C. (2009). The schools teachers leave: Teacher mobility in Chicago Public Schools.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. Retrieved from https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/schools-teachers-leave-teacher-mobility-chicago-public-schools

Alliance for Excellent Education (2014). On the path to equity: Improving the effectiveness of beginning teachers. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://all4ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PathToEquity.pdf

Aragon, S. (2016, May). Mitigating teacher shortages: Financial incentives. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States. Retrieved from https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Mitigating-Teacher-Shortages-Financial-incentives.pdf

Atteberry, A., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2017). Teacher churning: Reassignment rates and implications for student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,39(1), 3–30.

Backes, B., & Hansen, M. (2018). Reaching further and learning more? Evaluating Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture initiative. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. Working Paper No. 181. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED583619.pdf

Baker, B., Farrie, D., & Sciarra, D. G. (2016). Mind the gap: 20 years of progress and retrenchment in school funding and achievement gaps. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Baker, B., Sciarra, D. G., & Farrie, D. (2015). Is school funding fair? A national report card.4th ed.Newark, NJ: Education Law Center. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/state_edwatch/Is%20School%20Funding%20Fair%20-%204th%20Edition%20(2).pdf

Baker, B., Sciarra, D. G., & Farrie, D. (2018). Is school funding fair? A national report card. 7th ed.Newark, NJ: Education Law Center. Retrieved from https://edlawcenter.org/assets/files/pdfs/publications/Is_School_Funding_Fair_7th_Editi.pdf

Barnes, G., Crowe, E., and Schaefer, B. (2007). The cost of teacher turnover in five school districts: A pilot study. Washington, DC: National Commission on Teaching and America's Future. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b4ab/6eaa2ac83f4721044e5de193e3e2dec07ac0.pdf

Bastian, K. C., & Henry, G. T. (2015). Teachers without borders: Consequences of teacher labor force mobility. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(2), 163–183.

Bastian, K. C., & Marks, J. T. (2017). Connecting teacher preparation to teacher induction: Outcomes for beginning teachers in a university-based support program in low-performing schools. American Educational Research Journal, 54(2), 360–394.

Behrstock-Sherratt, E. (2016). Creating coherence in the teacher shortage debate: What policy leaders should know and do. Washington, DC: Education Policy Center, American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED582418.pdf

Behrstock-Sherratt, E., Bassett, K., Olson, D., & Jacques, C. (2014).From good to great: Exemplary teachers share perspectives on increasing teacher effectiveness across the career continuum.Washington, DC: Education Policy Center, American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED555657.pdf

Black, S., Giuliano, L., & Narayan, A, (2016, December 9). Civil rights data show more work is needed to reduce inequities in K-12 schools[Web log post]. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/12/08/civil-rights-data-show-more-work-needed-reduce-inequities-k-12-schools

Boe, E., Cook, L. H., & Sunderland, R. J. (2008). Teacher turnover: Examining exit attrition, teaching area transfer, and school migration. Exceptional Child, 75(1), 7–31.

Booker, K., & Glazerman, S. (2009). Effects of the Missouri Career Ladder program on teacher mobility.Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507470.pdf

Borman, G. D., & Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 367–409.

Boyd, D., Dunlop, E., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Mahler, P., O’Brien, R. O., & Wyckoff, J. (2012). Alternative certification in the long run: A decade of evidence on the effects of alternative certification in New York City. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Education Finance and Policy Conference, Boston, MA.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2011). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 303–333.

Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Ronfeldt, M., & Wyckoff, J. (2010).The role of teacher quality in retention and hiring: Using applications-to-transfer to uncover preferences of teachers and schools. Working Paper No. 15966. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w15966.pdf

Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2005). The draw of home: How teachers’ preferences for proximity disadvantage urban schools. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 24(1), 113–132.

Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2013). School leaders matter: Measuring the impact of effective principals. Education Next, 13(1), 62–69.

Bryk A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Burkhauser, S. (2017). How much do school principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 126–145.

Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT.pdf

Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(36), 1–32.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. E. (2014). Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2633–2679.

Chingos, M. M., & Peterson, P. E. (2011). It’s easier to pick a good teacher than to train one: Familiar and new results on the correlates of teacher effectiveness. Economics of Education Review, 30(3), 449–465.

Clewell, B. C., & Villegas, A. M. (2001). Absence unexcused: Ending teacher shortages in high-need areas. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Clotfelter, C. T., Glennie, E., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor. J. L. (2008). Would higher salaries keep teachers in high-poverty schools? Evidence from a policy intervention in North Carolina. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5), 1352–1370.

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2006). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85, 1345–1379.

Cohen-Vogel, L., Smith, T. M. (2007). Qualifications and assignments of alternatively certified teachers: Testing core assumptions. American Educational Research Journal, 44(3), 732–753.

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/ fulltext/ED012275.pdf

Cowan, J., & Goldhaber, D. (2016). National board certification and teacher effectiveness: Evidence from Washington State. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 9(3), 233–258.

Cowan, J., Goldhaber, D., Hayes, K., & Theobald, R. (2016). Missing elements in the discussion of teacher shortages. Educational Researcher, 45(8), 460–462.

Cullen, J. B., Koedel, C., & Parsons, E. (2016). The compositional effect of rigorous teacher evaluation on workforce quality. Working Paper No. 22805. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w22805.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., and Sykes, G. (2003). Wanted: A national teacher supply policy for education: The right way to meet the “highly qualified teacher” challenge.Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11(33), 1–55.

Dee, T. S., & Goldhaber, D. (2017, April). Understanding and addressing teacher shortages in the United States.The Hamilton Project. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/es_20170426_understanding_and_addressing_teacher_shortages_in_us_pp_dee_goldhaber.pdf

Donaldson, M. L., & Johnson, S. M. (2010). The price of misassignment: The role of teaching assignments in Teach for America teachers’ exit from low-income schools and the teaching profession. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 299–323.

Feng, L., & Sass, T. R. (2015). The impact of incentives to recruit and retain teachers in “hard-to-staff” subjects: An analysis of the Florida Critical Teacher Shortage program. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Working Paper No. 141. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED587182.pdf

Feng, L., & Sass, T. R. (2017). Teacher quality and teacher mobility.Education Finance and Policy, 12(3), 396–418.

Fortner, C. K., Kershaw, D. C., Bastian, K. C., & Lynn, H. H. (2015). Learning by doing: The characteristics, effectiveness, and persistence of teachers who were teaching assistants first. Teachers College Record, 117(11), 1–30.

Geiger, T., & Pivovarova, M. (2018). The effects of working conditions on teacher retention. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 604–625.

Gilmour, A. F., & Wehby, J. J. (in press). The association between teaching students with disabilities and teacher turnover. Journal of Educational Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Allison_Gilmour/publication/333675165_The_Association_Between_Teaching_Students_with_Disabilities_and_Teacher_Turnover/links/5cfe5251299bf13a384a7997/The-Association-Between-Teaching-Students-with-Disabilities-and-Teacher-Turnover.pdf

Gist, C. D., Bianco, M., & Lynn, M. (2019). Examining Grow Your Own programs across the teacher development continuum: Mining research on teachers of color and nontraditional educator pipelines. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(1), 13–25. Retrieved from https://sehd.ucdenver.edu/impact/files/JTE-GYO-article.pdf

Glazerman, S., Protik, A., Teh, B., Bruch, J., & Max, J. (2013). Transfer incentives for high- performing teachers: Final results from a multisite randomized experiment (NCEE 2014-4003). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED544269.pdf

Glennie, E. J., Mason, M., & Edmunds, J. A. (2016). Retention and satisfaction of novice teachers: Lessons from a school reform model. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(4), 244–258.

Goldhaber, D., & Cowan, J. (2014). Excavating the teacher pipeline: Teacher preparation programs and teacher attrition. Journal of Teacher Education, 65, 449–462.

Goldhaber, D., Gross, B., & Player, D. (2010). Teacher career paths, teacher quality, and persistence in the classroom: Are public schools keeping their best? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30(1), 57–87.

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Naito N., & Theobald, R. (2019). Making the most of student teaching: The importance of mentors and scope for change. Policy Brief No. 15-0519. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from http://caldercouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CALDER-Policy-Brief-15-0519.pdf

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Theobald, R., & Brown, N. (2015). Refueling the STEM and special education teacher pipelines. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(4), 56–62.

Goldhaber, D., Lavery, L., & Theobald, R. (2015). Uneven playing field? Assessing the teacher quality gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students. Educational Researcher, 44(5), 293–307.

Goldhaber, D., Quince, V., & Theobald, R. (2018). Has it always been this way? Tracing the evolution of teacher quality gaps in U.S. public schools.American Educational Research Journal, 55(1), 171–201.

Goldring, R., Taie, S., and Riddles, M. (2014). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey (NCES 2014-077). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014077.pdf

Gray, L., & Taie, S. (2015). Public school teacher attrition and mobility in the first five years: Results from the first through fifth waves of the 2007-08 beginning teacher longitudinal study (NCES 2015-337). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015337.pdf

Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552–2585.

Gross, B., & DeArmond, M. (2010). Parallel patterns: Teacher attrition in charter vs. district schools. Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education, University of Washington. Retrieved from http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/pub_ics_Attrition_Sep10_0.pdf

Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Residency_Innovative_Model_Preparing_Teachers_REPORT.pdf

Guin, K. (2004). Chronic teacher turnover in urban elementary schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12(42), 1–30.

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J., & Rivkin, S. (2004). Why public schools lose teachers. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 326–354.

Hanushek, E. A., Piopiunik, M., & Wiederhold, S. (2014). The value of smarter teachers: International evidence on teacher cognitive skills and student performance. Working Paper No. 20727. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w20727.pdf

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2006). Teacher quality. In E. A. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education,vol. 2 (pp. 1051–1078). Amsterdam, Netherlands: North Holland.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2007). Pay, working conditions, and teacher quality. The Future of Children,17(1), 69–86. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ795875.pdf

Hanushek, E. A., Rivkin, S. G., & Schiman, J. C. (2016). Dynamic effects of teacher turnover on the quality of instruction. Economics of Education Review, 55, 132–148.

Harris, D. N., & Adams, S. J. (2007). Understanding the level and causes of teacher turnover: A comparison with other professions. Economics of Education Review, 26(3), 325–337.

Henry, G. T., Bastian, K. C., & Smith, A. A. (2012). Scholarships to recruit the “best and brightest” into teaching: Who is recruited, where do they teach, how effective are they, and how long do they stay? Educational Researcher, 41(3), 83–92.

Henry, G. T., & Redding, C. (in press). The consequences of leaving school early: The effects of within-year and end-of-year teacher turnover. Education Finance and Policy.Retrieved from https://cdn.theconversation.com/static_files/files/269/withinyear_efp_final.pdf?1536242239

Hussar, W. J., & Bailey, T. M. (2014). Projections of education statistics to 2022 (NCES 2014-051).Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014051.pdf

Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534.

Ingersoll, R. (2003). Is there really a teacher shortage? Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Ingersoll, R. (2012). Beginning teacher induction: What the data tell us.Phi Delta Kappan, 93(8), 47–51. Retrieved from http://pdk.sagepub.com/content/93/8/47.full.pdf+html http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2012/05/16/kappan_ingersoll.h31.html

Ingersoll, R. M., & May, H. (2012). The magnitude, destinations, and determinants of mathematics and science teacher turnover. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(4), 435–464.

Ingersoll, R., May, H., & Collins, G. (2017). Minority teacher recruitment, employment, and retention: 1987 to 2013. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Minority_Teacher_Recruitment_REPORT.pdf

Ingersoll, R., & Merrill, E. (2017). A quarter century of changes in the elementary and secondary teaching force: From 1987 to 2012 (NCES 2017-092). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, L., & Stuckey, D. (2014). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated April 2014. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from http://www.cpre.org/sites/default/files/workingpapers/1506_7trendsapril2014.pdf

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated October 2018. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=cpre_researchreports

Ingersoll, R., & Perda, D. A. (2010). Is the supply of mathematics and science teachers sufficient? American Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 563–594.

Ingersoll, R., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233.

Jackson, C. K. (2018). What do test scores miss? The importance of teacher effects on non-test score outcomes. Journal of Political Economy, 126(5), 2072–2107.

Jacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL Balanced Leadership Program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332.

Johnson, S. M., & Birkeland, S. E. (2003). Pursuing a “sense of success”: New teachers explain their career decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 581–617.

Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), p. 1–39.

Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2013). Different teachers, different peers: The magnitude of student sorting within schools. Educational Researcher, 42(6), 304–316.

Kim, D., Koedel, C., Ni, S., Podgursky, M., & Wu, W (2017). Pensions and late-career teacher retention. Working Paper No. 164. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from https://caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/WP 164_0.pdf

Kini, T., & Podolsky, A. (2016). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teaching_Experience_Report_June_2016.pdf

Kirchhoff, A., & Lawrenz, F. (2011). The use of grounded theory to investigate the role of teacher education on STEM teachers’ career paths in high-need schools. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(3), 246–259.

Kraft, M. A. (2015). Teacher layoffs, teacher quality, and student achievement: Evidence from a discretionary layoff policy. Education Finance and Policy, 10(4), 467–507.

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588.

Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Yee, D. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal,53(5), 1411–1449.

Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235–261.

Lawrence, R. (2015). Promoting teacher professionalism: Lessons learned from Portland’s Professional Learning Based Salary Schedule. American Journal of Education Forum. Retrieved from: http://www.ajeforum.com/promoting-teacher-professionalism-lessons-learned-from-portlands-professional-learning-based-salary-schedule-by-rachael-b-lawrence/

Lawrence, R., Rallis, S. F., & Keller, L. A. (2014). Rewarding professionals to learn together: A tool for turnaround in Portland, Maine.Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA.

Lee, S. W. (2018). Pulling back the curtain: Revealing the cumulative importance of high-performing, highly qualified teachers on students’ educational outcome. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 359–381.

Liou, P. Y., Kirchoff, A., & Lawrenz, F. (2010). Perceived effects of scholarships on STEM majors’ commitment to teaching in high need schools. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21(4), 451–470.

Liou, P. Y., & Lawrenz, F. (2011). Optimizing teacher preparation loan forgiveness programs: Variables related to perceived influence. Science Education Policy, 95(1), 121–144.

Lochmiller, C. R. (2013). Leadership coaching in an induction program for novice principals: A 3-year study. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 9(1), 59–84.

Loeb, S., Darling-Hammond, L., & Luczak, J. (2005). How teaching conditions predict teacher turnover in California schools. Peabody Journal of Education, 80(3), 44–70.

Loeb, S., Kalogrides, D., & Horng, E. L. (2010). Principal preferences and the uneven distribution of principals across schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 205–229.

Maddock, A. (2009). North Carolina teacher working conditions: The intersection of policy and practice.New Teacher Center. Retrieved from http://www.jntp.org/sites/default/ les/ntc/main/pdfs/NC_TWC_Policy_Practice.pdf

Marinell, W. H., & Coca, V. M. (2013). Who stays and who leaves? Findings from a three-partstudy of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools. New York, NY: The Research Alliance for New York City Schools. Retrieved from https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/media/users/sg158/PDFs/ttp_synthesis/TTPSynthesis_Report_March2013.pdf